Rampage (38 page)

Authors: Lee Mellor

“I came to kill,” Lortie announced. “I’ll kill everyone — everyone in my way. I should have come at 2:00 p.m.” Enraged, he loosed a plethora of bullets, striking National Assembly cameraman Rejean Dionne in the right arm as he dove to the floor. Frustrated but feckless, Lortie seated himself in the Speaker’s chair, lording over the assembly like a mad king.

[61]

By this time, police SWAT teams had cordoned off the National Assembly and were beginning to evacuate people from the lower levels. There was no escape for Denis Lortie now, other than death. The question remained: how many more innocent people would he drag to the grave with him?

A Canadian Hero

Denis Lortie had arrived at the National Assembly on May 8, 1984, armed with a lethally accurate sub-machine gun, but undermined by a scattered mind. He would meet his match in the form of sixty-three-year-old Sergeant-at-Arms René Jalbert — a veteran of the Second World War and the Korean War whose cool, collected intellect would prove far more formidable. Jalbert arrived for work at the National Assembly at 9:30 a.m. and made his way to the Salon Bleu to ensure that the pages had prepared the room for the 10:00 a.m. meeting. Stepping out of the elevator on the second floor, he immediately heard a burst of machine-gun fire. Rather than attempting to escape, the unflappable Jalbert entered the Assembly chamber to find Lortie sitting upon the Speaker’s throne. Enraged at his interruption, Lortie sprayed the room with bullets. Jalbert remained calm. Noting that Lortie was dressed in army garb, Jalbert introduced himself as a fellow soldier, and offered Lortie a cigarette. When Lortie accepted it, Jalbert asked him if he could show the gunman his military identification. Once again, Lortie acquiesced.

“Seeing as I showed you my identification card, could you show me your identification card too, so that I would know who I am talking to?” Jalbert continued. Lortie handed Jalbert his ID. Slowly and methodically, the sergeant-at-arms built a rapport with the gunman, and suggested that they relocate to his office.

“Listen! I want to negotiate with you, I really want to have a talk with you and help you, but we’re going to do it in my office,” Jalbert insisted. “In the meantime, before we go, you must promise me that the pages that are still in the chamber will be allowed to leave.”

“Yes,” Lortie replied.

“Do you promise?”

Lortie pointed his gun at the ceiling, indicating that he would not open fire.

“All those who are in the chamber, leave right now!” Jalbert implored them. Three of the hostages hurried toward the exit. As Rejean Dionne passed by, Lortie said, “I’m sorry for wounding you, but that’s life!” A lone policeman remained in the chamber with a walkie-talkie, communicating the details of the situation to the officers outside the building.

“Why are you doing this?” Jalbert asked Lortie.

“I want to make everyone aware,” Lortie barked back. “I want to make the federal government, the provincial government, and everyone aware. That’s all.”

“You want to make them aware, but why?” Jalbert probed. “What do you want to tell them?”

“Oh!” the gunman sighed. “It’s too long, too difficult, we won’t talk about it; talk to me about something else.” By now, it was apparent that Lortie’s hatred was deflating like an old balloon. Jalbert offered again to take the conversation downstairs to his office where they could “find a solution” to Lortie’s “problem.” The weary Lortie agreed, and after a total of twenty-four minutes of negotiation, the two left the Salon Bleu together. Eventually they entered the office, where Jalbert introduced him to his secretary. In typical Quebecois tradition, Lortie bent down and kissed her cheek.

“You are a gentleman, Corporal,” remarked the sergeant-at-arms. “You treated that woman very nicely.” Once Lortie and Jalbert were alone inside his office, Jalbert asked him to place the C-1 on his desk, which Lortie did. A man of his word, Jalbert conversed with Lortie at length, helping him to understand the predicament he was in. Over the next few hours Lortie admitted to firing at the windows of the Citadelle, but when questioned about his motivation, would only reply repeatedly that his

“esprit”

had done it. Around noon, the gunman complained that he was hungry, and Jalbert had a security guard bring him a tomato sandwich. Interestingly, whenever Jalbert asked him about his family, Lortie replied that he didn’t want to talk about his “personal affairs” — a request which the sergeant-at-arms eventually honoured. On this topic, one cannot help but draw parallels with

Marc Lépine

(Chapter 1) and

Robert Poulin

(Chapter 2). Unlike the other two rampage killers, however, Lortie twice expressed deep regret for his actions, his eyes welling with tears.

“Listen, cry, that will make you feel better,” Jalbert encouraged the weeping corporal. “Don’t hold it back, cry as much as you want. The two of us are alone and I won’t tell a soul.”

*

When Lortie had finished, a great calm seemed to come over him. Jalbert decided to seize upon the opportunity.

“Listen! If you want, I’ll phone Valcartier, the military authorities. I’ve got a friend there; maybe he can find a solution to your problem. Will you let me phone?” His madness abating, Lortie seemed to be looking for a way out without losing face, and was amenable to the idea of surrendering to the military police. Jalbert called Colonel Armand Roy and explained the situation. Roy promised to send along the officers within forty-five minutes.

“It’s Colonel Armand Roy on the phone,” Jalbert turned to Lortie. “Do you want to talk to him to make sure I’m really speaking with a soldier at Valcartier?” Lortie drew a 9-millimetre revolver from his pocket, loaded it, and pointed it at Jalbert to guard against an ambush. He took hold of the receiver, spoke with Colonel Roy, and agreed to his proposal. When Lortie turned back to Jalbert, the sergeant-at-arms noted the safety catch was still off the pistol, and successfully convinced him to place the weapon on the table beside the C-1. In a further show of good faith, Lortie opened his shirt to permit Jalbert to search him for explosive devices. There were none.

At 2:22 p.m., Denis Lortie walked out of the National Assembly and into police custody, a cigarette dangling from his sheepish smile. His rampage had resulted in three deaths and thirteen injuries. René Jalbert was presented with the Cross of Valour, Canada’s highest civilian award for bravery, on November 9, 1984. He claimed to have never once been afraid for his life, and he shrugged off his courageous acts, saying, “Every sergeant-at-arms across Canada would have done the same thing.”

After three trials, on May 11, 1987, Denis Lortie was found guilty on three counts of second-degree murder and sentenced to life imprisonment with a ten-year minimum before eligibility for parole. Having undergone years of psychiatric treatment, he was released on full parole in 1996. Sixteen years later, the fifty-three-year-old has not reoffended. Lortie has stated that he was “disconnected from reality” at the time of the murders, and that as a result of his counselling, he now has “the tools” that he didn’t have before. He has since remarried, holds down a steady job, and has purchased a home. In 2007, Denis Lortie began a process of reconciliation with an unnamed family member of one of his victims.

*

Considering Jalbert subsequently informed the entire world of Lortie’s breakdown, it’s only fair to point out that he was not always a man of his word.

Chapter 12

The Set and Run Killer

When an incendiary device is planted in a deliberate attempt at mass murder, as

Alexander Keith Jr.

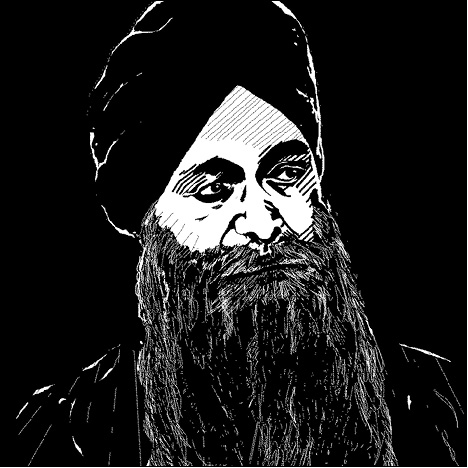

did in Bremerhaven, the results can shake the world to its very foundation. To this day, the worst mass murder in Canadian history remains the bombing of Air India flight 182 by Sikh extremists, resulting in the deaths of 329 people. Despite strong indications of a terrorist network’s involvement, only bombmaker Inderjit Singh Reyat has ever been convicted in connection with the attack.

Inderjit Singh Reyat: the only man to be convicted in connection with the Air India Bombing, Canada’s deadliest mass murder.

Inderjit Singh Reyat: the only man to be convicted in connection with the Air India Bombing, Canada’s deadliest mass murder.

Kay Feely

Enraged by the U.S. government’s siege of the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, on April 19, 1995, Timothy McVeigh retaliated by blowing up the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, extinguishing 168 lives in one of the deadliest acts of domestic terrorism in American history.

Forty-four people met their demise when an explosive device detonated on United Airlines flight 629 over Longmont, Colorado, on November 1, 1955. The perpetrator, John Gilbert Graham, had likely been inspired to commit his cold-blooded insurance scam by

J. Albert Guay

— a narcissist who holds the diabolical distinction of being the first airplane bomber in Canadian history. Also included in this chapter is set-and-run killer

Louis Chiasson

, who serves as an example of how stupidity and a pack of matches can be far more lethal than malice and a machine gun.

Other Set and Run mass murderers in this book:

Alexander Keith Jr.

author’s files

Albert Guay

“Well, at least I die famous.”

Victims:

23 killed

Duration of rampage:

September 9, 1949 (mass murder)

Locations:

Bomb planted in Quebec City, detonated in Sault-au-Cochon, Quebec

Weapon:

Time bomb

All that Glitters…

The youngest of five siblings, Joseph Albert Guay, born in 1917, had always been spoiled rotten by his mother. Whether it be candy or a new bicycle — whatever the baby of the family wanted, he got. Unsurprisingly, Albert grew up with a ferocious sense of entitlement, yet he was hardly born with a silver spoon. The Guay family hailed from Quebec City’s Lower Town — a rough working-class slum at the bottom of “the hill.” Overhead, historic battlements loomed like the impenetrable social barriers to the affluence he craved. Fellow Lower Towner and author Roger Lemelin would later describe the residents as “the mud of society.” Yet young Albert was determined to go down in history, and was often heard proclaiming, “You will hear more about me someday. I will make something of myself!” Where many boys in the post-war era dreamed of being soldiers or hockey players, Albert fantasized he was a powerful military commander, able to send large groups of obedient troops to their deaths to further his personal glory through conquest.

Perhaps it was this desire to hurt without the risk of being harmed himself which, upon the onset of the Second World War, spurred him to take a $40 per week position at Canadian Arsenals Limited in St. Malo. While his fellow Canadians fought bravely across the shores and fields of France, Albert operated a grinding machine in the armouries, and augmented his income by peddling watches. Instead of heroism, Albert strove to impress by creating a film-star façade, dressing stylishly and cruising around town in his shiny Mercury. He inhabited an inner world of fantasy, playing the role of the dashing leading man in his ultimately unspectacular existence. Every action was choreographed — he never drank or swore, and was known to spring from his car as it rolled to a stop for dramatic effect. A favourite topic of discussion was his various get-rich-quick schemes: ingenious plans which he was certain would come off without a hitch. It is a sad (if predictable) testament to reality that his superficial charm worked, with female co-workers swooning over him.

In 1942, he finally picked the starlet to his star — Rita Morel, a buxom young munitions-plant worker with Mediterranean features. At first their marriage was like a Hollywood romance, with the dapper Albert sweeping his new bride into a passionate kiss in the middle of the street. She bore him a baby daughter in 1945. That same year, the St. Malo armoury closed with the last shots of the Second World War, and their marriage soon devolved into an ongoing argument. Albert set up shop selling jewellery, eventually with branches in Baie-Comeau and Sept-Îles. He masked his incompetence at appraisal by hiring a watch repairman named Généreux Ruest, who had been crippled by tuberculosis. Ruest would assess the value of an item once the customer had left it in Albert’s care. Still, there were many occasions when Albert was duped by travelling salesmen who could spot a charlatan a mile away. The proverb “never con a conman” obviously does not hold true, for Albert was a confidence trickster to his core, walking to Mass every Sunday with a prayer book under his arm — a paragon of piety. Simultaneously, the oft-hustled hustler had finally discovered a way of making money in the jewellery business: insurance scams. “Robberies” and fires routinely plagued his stores, earning him thousands of dollars in compensation for insured items.