Rampage (39 page)

Authors: Lee Mellor

Guay’s greed was paralleled by his lust, and his eyes began to wander. In 1947, he met seventeen-year-old waitress Marie-Ange Robitaille at a dance. Though she knew he was a married man, Marie-Ange was charmed by the flashy businessman, and the two began a steamy affair. Employing the suave pseudonym “Roger Angers,” Albert introduced himself to her parents, and announced his plans to marry their daughter, for whom he had purchased an engagement ring. Apparently Albert was as lousy a philanderer as he was a businessman. Rita soon clued into his infidelities, and decided to pay the Robitailles a visit. When she showed them her wedding photographs, the jig was up. Rather than ending the affair, an infuriated Albert found Marie-Ange space in a rooming house owned by Marguerite Pitre, a former fellow munitions-plant worker nicknamed “The Raven” for her dark clothing, and Généreux Ruest’s sister. Albert had loaned the dark-haired, corpulent woman money to purchase the building, and she promised to watch over Marie-Ange closely. When his lover protested, he relocated her to a room in the Lower Town, denying her access to a key so she could rarely leave. Since moving away from her parents, Marie-Ange had become aware that she and Albert had no future together. He didn’t love her; instead he sought to possess her in the same jealous manner he had once done his wife, Rita. She absconded and boarded an overnight train to Montreal, determined to escape his grasp. As she waited for her bed to be made, Albert entered and calmly picked up her luggage. The terrified girl followed him back to the Lower Town in quiet compliance. Once back in her room, he struck her across the face and stole her shoes. Marie-Ange eventually fled his clutches, and returned to waitressing.

On the evening of June 24, Albert approached her on her way to work. He was armed with a revolver, and claimed to be depressed. When she told him that committing suicide was “a lazy way out,” he responded, “Maybe both of us will be lazy.” After following her to the restaurant, Albert ambushed her in the basement, prompting management to phone the police. He was arrested and charged with carrying an unlicensed pistol. Still, spoiled little Albert would not give up his toy, and after more stalking and serpentine persuasion, Marie-Ange finally agreed to settle with him in Montreal. Together they travelled to the big city, where Albert spent a small fortune buying her gifts. Ultimately, it was not enough. If he would not marry her, then she would leave him. At the time, provincial divorce legislation did not exist in Quebec. Only the passage of a private parliamentary act could end the Guays’ marriage; that, and the death of a spouse. As the multiple fires in his jewellery shop proved, when Albert Guay was around, accidents tended to happen.

Airplane Autopsy

On the morning of September 9, 1949, Rita Guay reluctantly boarded Canadian Pacific Airlines flight 108 at Quebec City airport. She didn’t want to fly all the way to Baie-Comeau to collect jewellery for Albert, but as always, he had browbeaten her into compliance. At 10:25 a.m., the wheels of the little DC-3 lifted into the air, spiriting Rita away into the azure sky.

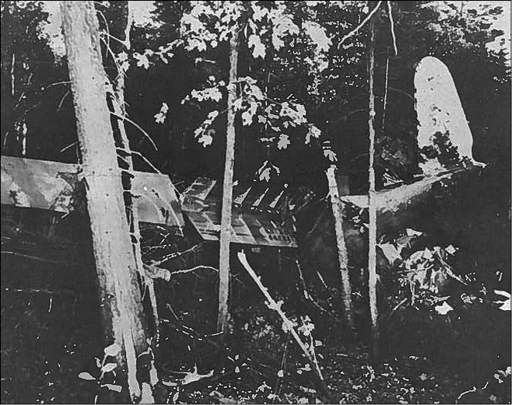

The wreckage of flight 108 in the hills of Sault-au-Cochon, Quebec.

The wreckage of flight 108 in the hills of Sault-au-Cochon, Quebec.

author’s files

Approximately fifteen minutes later, Patrick Simard spotted the plane flying overhead as he was fishing for eels seventy kilometres northeast of Quebec City in Sault-au-Cochon. There was a sudden bang, and he looked on in astonishment as the aircraft began careening left toward Cap Tourmente’s peak, a trail of smoke streaming behind it. Flight 108 smashed into the hillside, severing its wings upon impact. Simard hurried through the bushes to the crash site, and reached it an hour later. To his amazement, he found the plane jutting nose-first from the earth. Luggage and corpses were strewn haphazardly about the area. Though the smell of gas hung heavy on the air, miraculously there had been no fire. Simard scoured the wreckage for survivors, but found only husks of flesh and bone where life had once raged. He ran for help and came across some railway workers, who delivered the news to St. Joachim. From there it was relayed to Quebec City. Within hours, investigators from Canadian Pacific Airlines descended on the crash site like cops on a crime scene. They needed to know why the plane had malfunctioned and how many lives had been claimed. Upon observing the damage to the left front luggage compartment, the investigators immediately concluded that the DC-3 had been brought down by an explosive device. Fire extinguishers and storage batteries were discovered intact, ruling out any other possibility. As three of the passengers had been high-level executives at Kennecott Copper Corporation, some theorized that this was the work of a professional assassin. In all, twenty-three people had died — nineteen passengers, including four children, plus four crew members. The absence of fire left the corpses mostly intact and made them easily identifiable. Among them was Rita Guay.

On September 12, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police took charge of the investigation, aided by the Sûreté du Québec and the Quebec City Police Force. They soon learned that cargo had been loaded into the left front luggage compartment in Montreal, only to be fully emptied when the plane reached Quebec City, then loaded once more with cargo heading for Baie-Comeau — standard procedure. Wisely, the detectives examined the list of the passengers along with any life insurance policies taken out on them. Initially, nothing stood out as suspicious, but with financial gain the most obvious motive, they vowed to watch the family members of the deceased closely.

In the meantime, they questioned the Quebec City freight clerk who had been working on the morning of the explosion. Willie Lamonde did not remember anything out of the ordinary, other than loading some freight items. Scouring the airline’s records for the names of senders and intended recipients, they learned that one Madame Delphis Bouchard had intended to ship a twenty-eight-pound crate to Monsieur Alfred Plouffe of 180 Laval Street, Baie-Comeau. When the detectives learned that both Bouchard and Plouffe were fictitious, they began to suspect that a woman going by the alias of Delphis Bouchard had entrusted a crate containing an explosive device into the care of Willie Lamonde. The freight clerk had subsequently packed it into the DC-3’s luggage compartment. Lamonde was asked if he recalled a Madame Bouchard, and replied that he remembered an overweight woman arriving at the airport in a taxi. She had convinced the cabbie to haul the crate over to the weigh scale, then paid Willie the $2.72 shipping cost. Certain they were onto something, the investigators soon located the taxi driver, Paul Pelletier of the Yellow Cab Corporation. He described Madame Bouchard as an obese middle-aged woman, with dark hair accentuated by her black clothing. He had picked her up from Palais Railroad Station, driven her to the airport, and, after carrying the parcel for her, dropped her off behind the Château Frontenac hotel, where she began heading toward Lower Town. Around this time, the police formally announced in the

Star

newspaper that they were searching for the black-clad woman. The noose was slowly tightening around Albert Guay, and it wouldn’t be long before he was swinging from the gallows.

Crocodile Tears

Despite winning the 1949 Best Actor award for his role in

All the King’s Men

, Broderick Crawford could never have matched Albert Guay’s portrayal of a bereaved husband. Rita’s funeral was a magniloquent affair — her casket adorned with a cross of lilies reading, “From Your Dearest Husband.”

“You know how much I loved her,” Guay sniffled to Roger Lemelin in the packed funeral parlour. “But the important thing is she did not suffer. You don’t think she suffered, do you?” Feigning fortitude, Guay shakily advised another widower to “be brave, Monsieur Chapados. Do as I do: put your trust in God. I have lost my young wife.” Later, while standing with his daughter at Rita’s grave, he sobbed, “Look, dear, Mama is leaving us forever.” By the end of the ceremony, Guay appeared so emotionally overwrought that he needed assistance to get to his taxi.

Little did he know that he had already come under police suspicion. As Guay had not only paid fifty cents for $10,000 in flight insurance, which was routine at the time, but had also insured Rita specifically for another $5,000, they decided to examine his past. They learned that Guay had been fined $25 months earlier for waving a revolver in a restaurant due to some personal spat with a waitress. When they questioned the sultry young Marie-Ange, she not only confirmed knowing Guay, but also identified the black-clad woman as The Raven, Marguerite Pitre of 49 Monseigneur Gauvreau Street. The investigators clandestinely stationed taxi driver Paul Pelletier outside her home to identify her once she left. But Albert Guay got to her first. Arriving at the Pitre residence on September 20 with a copy of a

Star

article, he assured her that arrest was imminent.

“You had better do away with yourself,” he handed her some sleeping pills. “And leave a note saying you were the one who blew up the plane.” Terrified, Pitre washed down the yellow tablets, only to awaken later feeling painfully ill. Groggy, she telephoned for a taxi to take her to the hospital. As she plodded out of her front door, Paul Pelletier made a positive identification. Police soon arrived at Pitre’s bed at Infant Jesus Hospital to charge her with attempted suicide. After her release on September 23, 1949, they began to question her aggressively. Pitre denied having taken a taxi to the airport on September 9 — at least until the investigators produced Paul Pelletier to contradict her. When her puffy eyes fell upon the cab driver, Pitre broke down, confessing to her involvement in the bombing. She explained that she owed Albert Guay $600 which he had promised to forgive if she could procure him some dynamite from her connections in the construction industry. He claimed that it was to be used for clearing tree stumps from a friend’s property. Eventually she obtained ten pounds of dynamite and nineteen blasting caps.

With Pitre’s testimony as evidence, the police arrested Albert Guay mere hours later. Once in custody, he confessed to everything except the killings. His trial commenced on February 23, 1950. The killer con man seemed bored by the proceedings, except for a theatrical display of weeping when a pathologist testified that every bone in Rita’s body had been broken. Only when the object of his obsession, Marie-Ange Robitaille, took the stand did Guay lean forward in rapt attention. Dressed in a grey coachman’s hat and dark coat, the pallid beauty recounted their affair to the whole courtroom. She told of how after the plane crash, Madame Pitre had invited her over to 49 Monseigneur Gauvreau Street. She arrived to find a smiling Albert waiting for her. He had attempted to win her back, pointing out that with Rita now dead, nobody could stand between them. A stronger woman now, Marie-Ange had reiterated that their romance was nevertheless over. At one point, the examining attorney asked her if she still loved the defendant.

“No.” The pronouncement fired from her heavy, dark lipstick like a bullet. “I don’t have feelings for him anymore.” One particularly interesting witness for the prosecution emerged to testify that Guay had offered him a paltry $500 to poison Rita. Unlike the beads of water that had fallen so emptily from Albert Guay’s eyes, tears streamed from Judge Sevigny’s face as he showed the jury a photograph of Rita’s mangled corpse, imploring them to fulfill God’s law. In the end, they deliberated only seventeen minutes before finding the defendant guilty of murder. “Your crime is infamous. It has no name,” Sevigny declared, sentencing Guay to death by hanging.

The Raven: Nevermore

While awaiting his execution in Bordeaux Prison, Albert Guay alleged that Marguerite Pitre and her brother Généreux Ruest, the crippled clockmaker, had been knowingly involved in his conspiracy to blow up flight 108. He claimed to have guaranteed them money from Rita’s insurance policy in order to secure their co-operation. In June 1950, both Ruest and Pitre were arrested and charged with murder based on evidence from Guay’s own mouth. Defenders of the co-accused posit that Guay had falsely implicated them in his plot so that he would be called to testify at their trials, delaying his date with the hangman.

Investigators found a blackened segment of corrugated cardboard in Ruest’s workshop, and sent it to a laboratory in Montreal for forensic analysis. Judging by the black deposits on the material, it was determined that blasting caps had been detonated in the workshop, with cardboard used to shield the explosion. The same black patterns were found inside the wreckage of the DC-3’s left luggage compartment. Ruest admitted that he had built a time bomb mechanism for Albert using an alarm clock, and that they had performed tests with it in his workshop; however, he had been informed that the purpose of the device was to remove tree stumps. After the explosion, Ruest claimed to have been afraid to divulge his suspicions of Guay’s involvement to the authorities because he assumed they wouldn’t believe his version of the events.

During Ruest’s 1950 trial, Albert Guay appeared on the witness stand to testify against his former employee. Doing little to help their cause, Marguerite Pitre was charged with uttering death threats to witnesses, and had to be forcibly removed from the courtroom. The most damning piece of evidence against Ruest came when a munitions worker testified that the crippled watchmaker had asked his advice on how to detonate twenty sticks of dynamite — hardly a blast fit for a tree stump. In December 1950, Ruest too was convicted of murder and sentenced to die.