Re Jane (3 page)

Authors: Patricia Park

apter 4

Brooklyn

I

n the row of brownstones between Clinton and Henry Streets in Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn, 646 Thorn Street was the only house on the block with a string of red paper lanterns hung in the doorway. To the left of the door was a hooded bay window, and from where I stood it gave the impression that the house was winking at me, as if we were both in on the same joke.

Brownstones were not part of the indigenous Queens architecture. Our houses were sometimes clapboard, redbrick, or concrete, more often than not aluminum-sided. The single-family detached houses lay farther east, in the neighborhoods jutting into the Little Neck Bay.

I was in Brooklyn for my interview for that nanny job. I couldn't tell you exactly what had compelled me to apply, except that I was being practical. I took a hard look at my situation: financial firms usually recruited in the fall for summer hires. The soonest I could start a new job would be one year from now. Temping or bookkeepingâmy other options in the interimâwas not all that attractive on a résumé; baby-sitting wouldn't look

that

much worse. (Not that I would dare put “nanny” under “work experience”; I'd have to explain away the time off with the excuse that I was studying for the GMATs. Or skipping about Europe with a backpack.) But maybe the real impetus had been curiosity. Who was this family with an adopted daughter from China? They were willing to hire and shelter and feed a whole other person, just for their one daughter. And Hannah used to say

I

was the lucky one. She let me tack on my piano lessons at the end of Mary and George's. (By the time that piano teacher got to me, she'd heave a

nunchi

-ful sigh, so I'd let her wrap up our sessions after a hasty set of Czerny exercises, my fingers tripping over the scales.)

When I called the ad's box number at the bottom of the paper, someone named Ed Farley answered. Over the phone he was clipped, his voice gravelly, with a Brooklyn accent. After a few basic questions, he rattled off a date and time, along with his address. But he did not pass the receiver to Mrs. Ed Farley.

I knew the Ed Farley type. He shared the same raspy tone as the older Irish men from the neighborhood who shopped at Food. Someone like Mrs. O'Gall's son. (Once a year, the day after Christmas, her son would take her grocery shopping and Mrs. O'Gall would parade him around the store. Then he'd return to his Greek Revival four-bedroom in Westchesterâshe'd shown us picturesâuntil the next year.) By the end of that phone conversation, I had outfitted Mr. Farley in a short-sleeved button-down yellowed with pit stains, brown polyester pants hemmed a few inches too short, and black orthopedic shoes with thick cushioned soles. I went ahead and added a middle-aged paunch, fading tufts of yellow hair, and sagging jowls, smattered with liver spots.

When the door swung open, the man standing behind it looked

nothing

like the Ed Farley I'd imagined. He was past the youthfulness of his twenties but too boyish for middle age; he was probably in his mid- to late thirties. He had a full shock of blond hairâthe kind of natural blondness I used to see more as a kid but these days rarely made an appearance on the 7 train. His deep-set eyes were the same shade of blue as Shea, but instead of the stadium's flat, matte color, Mr. Farley's eyes were bright with vigor. He had a square forehead, a straight nose, high cheekbones, and a strong jawline. He shared the same conventionally handsome features of the male models in the Polo ads, but there was still something a touch too Irish, a touch too hard-worn about his face to be considered all-American.

Then I realized that while I was exploring his face, this man had also been probing mine. It was not in the same parsing way Korean eyes looked at me, trying to discern the percentage of my genetic split. Judging by the tight line his lips made, I could tell that mine was a face that displeased him. I grew self-conscious; I took a step back.

He spoke. “You Jane Re?” he said. There was that thick Brooklyn accent.

I nodded, too shy to trust my own voice. Our family name, in the original Korean, was pronounced “Ee”âless a last name than a displeased squeal. “Lee” was its most common Western perversion, but there were others: Rhee, Wie, Yee, Yi. Re was a bastard even among the other bastardizations.

“Ed. Ed Farley.” He stuck out his hand. I expected it would be rough to the touch, but my fingers glided over the smooth skin of his palm.

I followed Ed Farley down a dark, narrow hallway, lined with carved African masks. Mr. Farley was not tallâmaybe only two inches taller than meâbut under his buttoned-up shirt I could tell he was broad-shouldered and lean. He had the kind of natural muscles that made you think of hours spent not at the gym but on construction sites, lifting beams of wood and steel, or warehouses, loading pallets of merchandise onto trucks.

I adjusted my suit blazer and pulled down the hem of my skirt. If something happened to me, I knew what Sang would say:

Telling you so.

I'd had to pretend I'd gotten an interview with a bank.

After a seemingly endless hallway, we finally turned left and entered the living room. We'd just made a loop around the house, only to wind up right back at the front. The bay window down at the far end of the room, draped in crimson velvet curtains, was the same hooded window that had stared out at me from the street. Dark wood bookshelves, crammed with books, floated on the walls, with more books heaped in piles on the floor.

There was a rustling of the curtains; I saw a small foot poking out, then a little leg, then a little girl. An Asian girl. She had a tiny frame but a large head, its largeness further emphasized by the unfashionable bowl cut of her stick-straight black hair. She didn't look stereotypically ChineseâI might even have mistaken her for Korean. She jumped down from her window perch and bounded toward me with purposeful strides. She looked like a colt: half trotting, half tripping. One arm was sticking out in the air, ready to receive mine. The other held an oversize newspaper.

Her outstretched hand reached me first. “You must be Jane Re. My name's Devon Xiao Nu Mazer-Farley, and next week I start the fifth grade. It's a real pleasure to meet you.” By the time she finished speaking, the rest of her body had caught up to her hand.

We shook; the girl had a surprisingly tight grip.

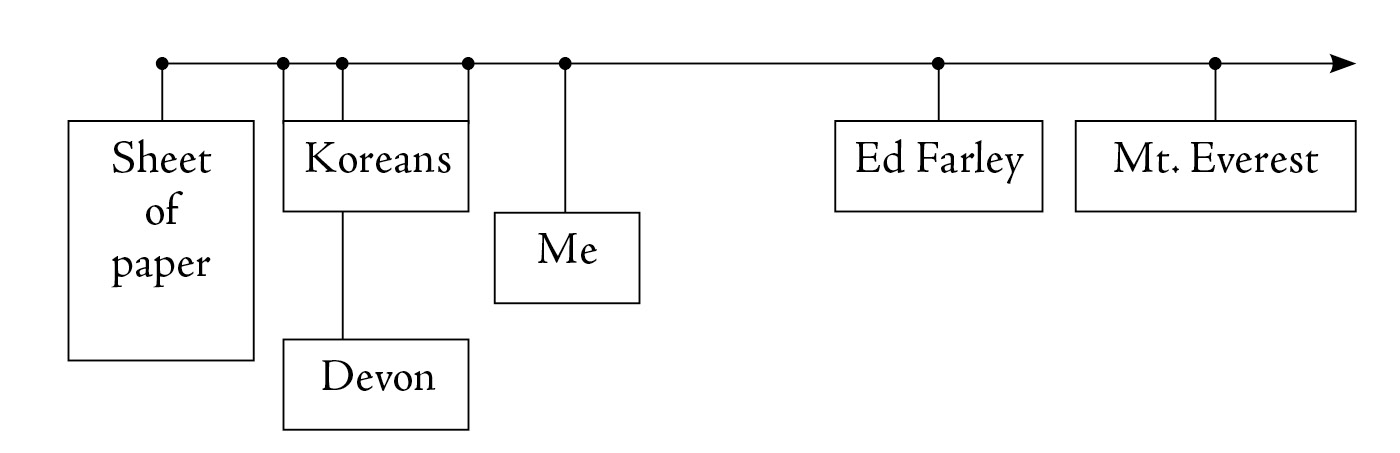

Devon Xiao Nu Mazer-Farley's face was so different from Ed Farley's: it was shallow, like swift strokes on a sheet of clay. On a scale of increasing facial three-dimensionality, things would look something like:

I heard light, scampering footsteps, like a mouse's. I turned around and saw a woman hurrying toward me, arm outstretched, frizzy gray hair streaming behind her. She squeezed my knuckles. “You must be Jane. I'm Beth, Devon's mom. It's a real pleasure to meet you.”

This

was Mr. Farley's wife? She looked a decade too old for him. “A real pleasure to meet you, too, Mrs. . . . Farley.”

“

Mrs.

Farley!” she laughed.

“That kind of has a nice ring to it,” Mr. Farley said from the couch, but too softly for the woman to hear.

“Please,

call me Beth,” she said to me. “But for the record, it's Dr. Mazer.”

I apologized for my error, but with a swipe of her arm Beth waved it away.

“Please, excuse me. I must return to my reading,” Devon said to no one in particular, returning to her window nook, disappearing altogether behind the curtains.

Beth gestured to the seat next to Ed Farley. “Make yourself comfortable.”

I looked at the wicker love seat where he was sittingâthere was maybe a foot and a half of clearance. It would be a very tight squeeze.

“Dr.âBeth, please, sitâ”

But Beth insisted. “I've been parked on my ass all day.” She said “ass” right in front of her daughter and didn't bother to censor herself. Only Mr. Farley cleared his throat.

I was made to sit. I pressed my knees together, so they wouldn't knock into Ed Farley's. I could feel his tense thighs against mine. Beth began pacing around the room, swinging her arms vigorously. Hannah did the same thing to increase circulation. Black, wiry sprouts of hair peeked out from under Beth's arms through her sleeveless, shapeless tunic top.

I couldn't picture a more mismatched pair than Beth Mazer and Ed Farley. Beth looked like she was well into her forties: her face was gaunt, with yellow circles under her large, dark eyes. Blackheads studded her nose. Perhaps if Beth dyed her hair or blow-dried her frizzy strands straight, she might have minimized the age gap between them. Still, she seemed to carry herself with the confidenceâand entitlementâof a younger, prettier woman.

“Jane!” Beth said. “We are thrilled to meet you. Tell us everything.”

Everything?

I reached for the file folder in my bag. “Here is my résuméâ”

Beth waved it away. “We want to get to know

you

. Let's have a conversation.”

Weren't we already? “Um, okay.”

“You just graduated from college, right? What was that experience like?”

Beth's question was oddly open-ended.

“It was good, I guess. I double-majored in finance and accounting.”

“Isn't that a shame, Beth.” It was Mr. Farley who spoke.

“Ignore him, Jane. That comment was more about me than about you.” Over my head they exchanged a look. Beth went on. “I suppose the cat's out of the bag, Jane: I have something of a predisposed bias against banker types. They

are

my mother's people!

Clearly

I'm a self-hater. So it goes, so it goes.” Clearly Beth was an oversharer. As she spoke, her cheeks did not flush red, the way most normal people's would when they realized they were divulging too much information.

She went on. “But frankly, Jane, I'm surprised you're applying for this kind of job. You seem like a bright, sensitive young woman, despite your degree.”

It wasn't a question, so I didn't answer it.

“Tell us where you're from.”

“Queens. Flushing.”

Beth called out to Devon, “Remember, sweetie? The last time we were in Queens? When I took you to see the Mets play the Giants?”

Devon turned from her window perch. “And the Mets

lost,

” she said, scrunching her nose. “They

always

lose.”

“You've got to believe, sweetie.”

People only ever have two stories about Queens: bad times at JFK and bad times at Shea Stadium.

“And what do your parents do out there?” Beth backpedaled hastily. “That is, if you're comfortable talking about it. I know

I

hate it when people are always like, âAnd what do

your

parents do?' God, look at me! I'm turning into my mother.” Beth made an exaggerated shudder, presumably for comic effect, but when she finished that routine, she stared down at me, waiting for an actual answer.

“My uncle has a grocery store in Flushing.”

“Your . . . uncle?”

I found myself craving the sterility of corporate-finance interviews.

“I live with his family. TheyâMy mother died a while ago.”

The curtains parted, and Devon came bounding across the room. She put her face right up to mine. “How did your mother die?”

“Devon!” Beth said sharply. I exhaled a sigh of relief. But then she said, “It's not polite to ask that. It's better to say, âHow did your mother pass away?'”

Devon corrected herself, her small hand giving my shoulder a reassuring pat. Then her mother

began patting my

other

shoulder. The two exchanged a conspiratorial look of shared pity. This interview was starting to make me feel

tap-tap-hae.

I turned my head away, because I couldn't trust myself not to contort my face with displeasure. You

of all people need to worry about wrinkles.

I caught Ed Farley's eye.

“If she doesn't want to talk about it, she doesn't want to talk about it,” Mr. Farley muttered before picking up the newspaper. I was surprised by his display of

nunchi.

Thankfully, the conversation moved on to other topics. Beth settled to the floor and crossed her legs. She lectured, and I listened. She told me she was a professor of women's studies at Mason College. (“Up for tenure next year!” she added in a strangely anxious, high-pitched tone.) I remembered seeing their ads on the subwaysâ

WHERE POETS BEC

OME PARTICLE PHYSICI

STS . . . AND VICE VERSA

!, the tagline readâabove a set of multihued youths leaping in the air. Mr. Farley taught high-school English at a prep school downtown. They had met at Columbia as graduate students in the English department. She talked about Devon's adoption processâ“We're trying to revise the adoption rhetoric by calling it an âalternative birth plan'”âas well as the responsibilities that came with the au pair position.

“I don't want someone who's just going to clock in and out each day. We want you to grow and become part of our family,” she said. “We wantâ”