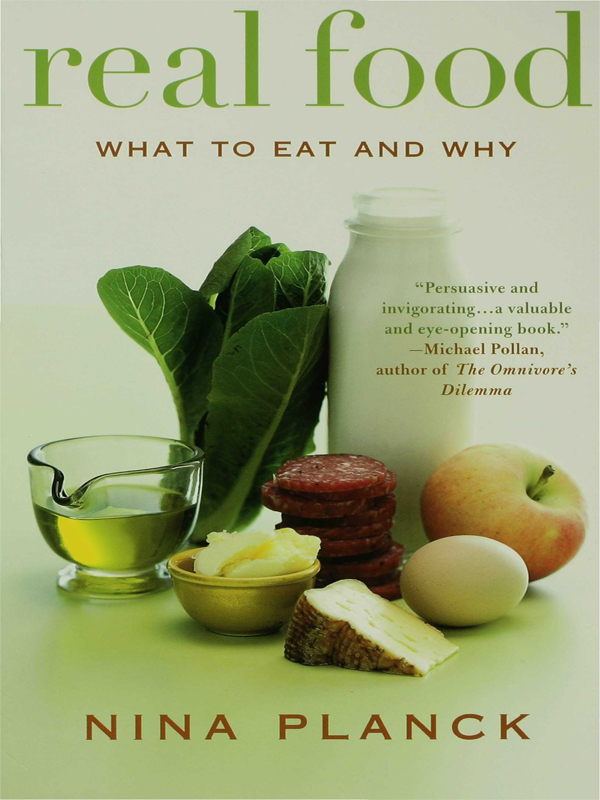

Real Food

Authors: Nina Planck

real food

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Farmers'

Market Cookbook

real food

WHAT TO EAT AND WHY

NINA PLANCK

BLOOMSBURY

Copyright © 2006 by Nina Planck

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from

the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Bloomsbury

USA, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Published by Bloomsbury USA, New York

Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers

The ideas and suggestions in this book are not

intended to replace the services of a health professional.

The reader is advised to take professional advice before

making significant changes in diet.

All papers used by Bloomsbury USA are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. The manufacturing

processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE HARDCOVER EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

Planck, Nina, 1971-

Real food: what to eat and why / Nina Planck.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN-13: 978-1-59691-144-4 (hardcover)

ISBN-10: 1-59691-144-1 (hardcover)

1. Nutrition— United States. 2. Diet— United States. I. Title.

TX360.U6P63 2006

613.20973— dc22

2005033624

First published in the United States by Bloomsbury in 2006

This paperback edition published 2007

Paperback eISBN: 978-1-59691-342-4

10 9 8 7 6 5 4

Typeset by Palimpsest Book Production Ltd, Grangemouth, Stirlingshire Printed in the United States of America by Quebecor

World Fairfield

Contents

1. I Grow Up on Real Food, Lose My Way, and Come Home Again

First I Explain What Real Food Is

We Become Vegetable Farmers in Virginia

I Am Forced to Eat Homemade Food

My Virtuous Diet Makes Me Plump and Grumpy

In London I Am Rescued by Farmers' Markets

I Discover Weston Price and His Odd Notions

Everywhere I Go, People Are Afraid of Real Food

2. Real Milk, Butter, and Cheese

I Am Nursed on the Perfect Food

I Remember Milking Mabel the Cow

Milk, Butter, Cholesterol, and Heart Disease

I Describe the Virtues of Raw Milk

I Learn to Appreciate Proper Cheese

Why Even Vegetable Farms Need Animals

How Factory Farms Wreck the Natural Order

Why Grass Is Best (and I Don't Mean for Tennis)

The Virtues of Beef, Pork, and Poultry Fat

I Try the Winston Churchill Diet

I Am Skeptical That Red Meat Causes Cancer

How Our Brains Grew Fat on Fish

Life After Salmon: Obesity, Diabetes, and Heart Disease

Are You Depressed? Try Eating More Fish

Why I Never Rebelled Against Vegetables

I Learn How to Answer the Question:

Are You Organic?

Some Surprising Facts About Fats

If You Have Only Two Minutes to Learn About Fats, Read This

How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love Saturated Fats

My Opinion of the Minor Vegetable Oils

How the Margarine Makers Outfoxed the Dairy Farmers

How Fake Butter Causes Heart Disease

Why I Don't Eat Corn, Soybean, or Sunflower Oil

The Abominable Egg White Omelet

Traditional and Industrial Soy Are Different

I Explain the Difference Between Good Salt and Bad

Chocolate: The Darker the Better

I Grow Up on Real Food., Lose My Way, and Come Home Again

First I Explain What Real Food Is

WHEN I WAS GROWING UP on a vegetable farm in Loudoun County, Virginia, we ate what I now think of as

real food.

Just about everything at our table was local, seasonal, and homemade. Eating our own fresh vegetables certainly made me proud;

they tasted better than the supermarket vegetables other people ate. But I regarded homemade granola, whole wheat bread, and

chicken livers— not to mention the notable lack of store-bought processed foods in brightly colored boxes in our kitchen—

as uncool. Today, my embarrassment over the simple American meals we ate is long gone, and I regard the food I grew up on

as the very best. It's true that in certain quarters these days, sautéed chicken livers

are

fashionable, but I don't care about that; I prefer real food because it's delicious and it's healthy.

What is

real food}

My rough definition has two parts. First, real foods are

old.

These are foods we've been eating for a long time— in the case of meat, fish, and eggs, for millions of years. Some real foods,

such as butter, are more recent. It's not absolutely clear when regular dairy farming began, but we've been eating butterfat

for at least ten thousand years, perhaps as many as forty thousand. By contrast, margarine— hydrogenated vegetable oil made

solid and dyed yellow to resemble traditional butter— is a modern invention, merely a century old. Margarine is not a real

food.

Consider the soybean. Asians have been eating foods made from fermented soybeans, such as miso, tofu, and soy sauce, for about

five thousand years. Without fermentation, the soybean isn't ideal for human consumption. But most of the modern soy products

Americans eat are not traditional soy foods. The main ingredient in modern soy foods and many processed foods, such as low-carbohydrate

snack bars, is "isolated soy protein," a by-product of the industrial soybean oil industry. This unfermented, defatted soy

protein is not real food.

Second, real foods are

traditional.

To me,

traditional

means "the way we used to eat them." That means different things for different ingredients: fruits and vegetables are best

when they're local and seasonal; grains should be whole; fats and oils unrefined. From the farm to the factory to the kitchen,

real food is produced and prepared the old-fashioned way— but not out of mere nostalgia. In each of these examples of real

food, the traditional method of farming, processing, preparing, and cooking

enhances

nutrition and flavor, while the industrial method diminishes both.

• Real

beef

is raised on grass (not soybeans) and aged properly.

• Real

milk

is grass-fed, raw, and unhomogenized, with the cream on top.

• Real

eggs

come from hens that eat grass, grubs, and bugs— not "vegetarian" hens.

• Real

lard

is never hydrogenated, as industrial lard is.

• Real

olive oil

is cold-pressed, leaving vitamin E and antioxidants intact.

• Real

tofu

is made from fermented soybeans, which are more digestible.

• Real

bread

is made with yeast and allowed to rise, a form of fermentation.

• Real

grits

are stone-ground from whole corn and soaked with soda before cooking.

Industrial food is the opposite of real food. Real food is old and traditional, while industrial food is recent and synthetic.

The impersonation of real food by industrial food, by the way, is neither accidental nor hidden. Industrial food like margarine

is

intended

to be a replica of a traditional food— butter. Real food is fundamentally conservative; it doesn't change, while industrial

food, by contrast, is under great pressure to be novel. The food industry is highly competitive and relentlessly innovative,

producing thousands of new food products every year. Most of these "new" foods are merely new combinations of old ingredients

dressed in a new shape (individually wrapped cheese slices instead of the traditional wheel of pressed cheese) or new packaging

(whipped cream in an aerosol can). Or the new recipe has been tweaked to ride the latest food craze (cholesterol-free cheese,

low-carbohydrate bagels). Real food, on the other hand, doesn't change because it doesn't have to. My morning yogurt is a

masterfully simple recipe for cultured milk, passed down for thousands of years.

So that's my custom definition of

real food:

it's old, and it's traditional. To lexicographers, sticklers, and nitpickers (you know who you are), it's no doubt hopelessly

imprecise and incomplete, but I hope it's clear enough for our purposes.

People everywhere love traditional foods. They're fond of a nice steak, the crispy skin of roast chicken, or mashed potatoes

made with plenty of milk and butter. But they're afraid that eating these things might make them fat— or, worse, give them

a heart attack. So they do as they're told by the experts: they drink skim milk and order egg white omelets. Their favorite

foods become a guilty pleasure. I believe the experts are wrong; the real culprits in heart disease are not traditional foods

but industrial ones, such as margarine, powdered eggs, refined corn oil, and sugar. Real food is good for you.

Does that mean you should enjoy real bacon and butter not because they're tasty but because they're actually

healthy}

In a word, yes. Some might mock this as a characteristically American case for real food— call it the Virtue Defense. Gina

Mallet, an Anglo-American "food explorer" who defends real foods, including beef and raw milk cheese, in

Last Chance to Eat: The Fate of Taste in a Fast Food

World,

calls the modish philosophy

healthism

— and her intent is not to flatter. As scientists began to blame the diseases of civilization on diet, Mallet writes, "a

new philosophy emerged, based on the notion that death could be delayed, perhaps even cheated, if a person monitored every

single piece of food she ate." I'm concerned about nutrition, but I wouldn't call myself a healthist. For one thing, living

forever doesn't interest me, and for another, flavor does.

Someone else— a French chef perhaps— might take a different approach in defense of real food. Less interested in health, he

might champion pleasure for its own sake. Great— I'm all for pleasure. If the sheer sensual joy of eating shirred eggs or

homemade ice cream is enough for you to shed your guilt, throw away phony industrial foods, and return to eating real foods,

all the better. I'll leave the nature of taste and satisfaction, guilt and pleasure to the cultural critics and moral philosophers.

This

book is about why real food is good for you.

We Become Vegetable Farmers in Virginia

MY PARENTS CHOSE TO FARM, but I didn't. My father had a doctorate in international relations from Johns Hopkins and taught

political science at the State University of New York in Buffalo, where I was born in 1971. A bright young professor, he got

tenure early, and he could teach anything he wanted. My mother, for her part, was at home with three young children and very

happy. But they always had unconventional plans and Utopian ideas: unsatisfied with our local public school in Buffalo, they

started and ran a neighborhood school with other parents. They loved physical work and kept a plot in a garden outside of

town.

In January 1973, our friends Tony and Mariette Newcomb came to see us in Buffalo. They brought eggs and beef they had raised

on their farm in Virginia. "We were knocked out by that," my father said. That very year, Dad quit teaching and we moved south

to Virginia to learn vegetable farming from the Newcombs. Committed to farming before they'd even tried it, they also bought

sixty acres of farmland in Loudoun County, Virginia, for seventy-five thousand dollars they cobbled together with loans from

friends and family. My sister, Hilary, was ten years old, Charles was six, and I was two. They wanted us to grow up on a farm.

Our first years farming as apprentices to the Newcombs were wonderful and strange, very different from the life of a professor's

family. Mom and Dad worked all the time, and we lived simply. With no kids my age to play with, I was often lonely hanging

around the farm or playing at make-believe grocery shopping at our farm stand. In many ways it was a hard life. But however

sore and tired they were, my parents loved farming, and soon we moved west to our own place, in the tiny hamlet of Wheatland,

Virginia. We arrived at the farm late on Christmas Eve in 1978. All our things, including a few pieces of farm equipment,

were tied up in a rickety pile on the back of our green flatbed Ford. There was too much snow to drive up to the house, and

there was no driveway anyway, so we parked at the edge of the property and walked a quarter of a mile.

The old tenant house had little charm. The kitchen floor was covered with a dirty mustard carpet. Under that was linoleum;

under that, plywood, hiding yellow pine floorboards. The sink drained through the kitchen wall into the backyard. We heated

the house and water for baths with wood fires. But my parents are relentlessly cheerful and practical, and over the years

we fixed up the house, scrubbing, scraping, and painting, with the simple faith that natural materials, such as wood floors,

are beautiful no matter how modest or worn.

In the spring of 1979, we became farmers. While other kids played soccer and went to the beach, Charles and I spent the long

humid Virginia summers hoeing, weeding, mulching, picking, and selling vegetables. Some farm chores are part of the past;

now we mulch every crop to keep weeds down, so there's hardly any hoeing, but I spent many dusty hours hoeing rocky pumpkin

fields back then. Other lost tasks I think of more fondly. On the mulch run we brought home scratchy hay bales from local

farms. You had to be strong to toss them up onto the wagon to the stacker, but today we unroll little round bales like carpets

down tomato aisles. It's much more civilized but less romantic.

When I was eight years old, I began to sell our vegetables at roadside stands in the towns near our farm. After my parents

dropped me off, I would set up the table, umbrella, and signs, and wait for people to buy our tomatoes, zucchini, and sweet

corn. Stand duty was often lonely, and sometimes scary for a young girl, especially when it got dark. More to the point, we

couldn't make a living this way— not with sales of $200 here or $157 there. That winter, my parents took part-time jobs— Dad

as a handyman, and Mom waiting tables at the Pizza Hut in Leesburg— to make ends meet.

Only one year later, in 1980, the first farmers' market in our area opened in the courthouse parking lot in Arlington, Virginia,

and everything changed. We picked and bunched beets and Swiss chard and drove into town. Scores of grateful customers flocked

to our vegetables, as if they had waited all their lives for roadside stands to come to the suburbs of Washington, D.C. That

summer we took our vegetables to three weekly farmers' markets, and soon we abandoned roadside stands altogether. With farmers'

markets, we began to make a modest profit and farming became a lot more fun. Today, my parents are in their midsixties, and

they still make a living exclusively from selling at farmers' markets. They sell twenty-eight varieties of tomatoes, a dozen

different cucumbers, garlic, lettuce, and many other vegetables at more than a dozen markets a week in peak season.

We never liked the term

back to the landers

for people who gave up city jobs for farm life. How can you go back to a place you've never been? Yet that's what people called

us. I always thought of us as farmers, because farm life was all I ever knew. I have no memories of being a professor's daughter

with a stay-at-home, intellectual mother, only of my parents coming in wet from the morning corn pick in the very early days

farming with the Newcombs. Even now, after living in Washington, Brussels, London, and now New York City, I still think of

myself as a farm girl, happiest when I'm around tomatoes and bugs and creeks.

I Am Forced to Eat Homemade Food

MY MOTHER WAS A natural, if amateur, scientist with an interest in biology, nutrition, and babies. She read about the pioneering

experiments of Clara Davis in the 1920s and '30s. Davis set out healthy, whole foods for infants and let them eat anything

they wanted for months at a time. The smorgasbord included beef, bone marrow, sweetbreads, fish, pineapple, bananas, spinach,

peas, milk and yogurt, cornmeal, oatmeal, rye crackers, and sea salt. At any given meal, the choices babies made could be

extreme: one baby ate mostly bone marrow; others loved bananas or milk. One occasionally grabbed handfuls of salt. Over time,

however, the babies chose a balanced diet, rich in all the essential nutrients, surpassing the nutritional requirements of

the day, and they were in excellent health. The nine-month-old boy with rickets drank cod-liver oil (rich in vitamin D) until

his rickets was cured; then he ignored it.

The Clara Davis experiments were limited, and to my knowledge, never repeated. Proven or not, the idea made a deep impression

on my mother. She believed that anyone, even an uninformed baby or child— perhaps

especially

a baby or child— could feed himself properly on instinct alone if you gave him only healthy foods, and that was how we ate—

at home anyway. There was some leeway for junk food on car trips (Oreos were a treat), and on the rare occasions when we ate

out, we could order anything we wanted. At home, however, there was only real food, and my parents never told us what to eat

or how much or when.

My mother's other nutritional hero was Adelle Davis, the best-selling writer who recommended whole foods and lots of protein.

Before dinner, Mom put out carrot, apple, or turnip sticks so we would eat raw fruits and vegetables when we were hungry for

a snack. Main dishes were basic American fare: fried chicken, tuna salad, spaghetti, quiche, meatloaf, potato pancakes with

homemade applesauce. There were many frugal dishes, such as chicken hearts with onions, and we ate a lot of rice and beans.

At dinner we always had several vegetables and a large green salad.