Real Food (5 page)

Authors: Nina Planck

The young woman at Murray's doesn't know that you need the fat in milk to digest the protein and absorb the calcium. If she

struggles with her weight, she may discover— as million of Americans have, after thirty years of dubious advice— that eating

foods engineered to be low-fat doesn't work, especially when you eat more calories because the food is unsatisfying. Also,

the latest research indicates that milk, yogurt, and cheese actually aid weight loss, perhaps due to the effects of calcium

on fat storage.

At my house and at the farm, we eat the way people did for thousands of years. That means all the foods they tell you to avoid:

red meat, whole milk, sausage, butter, and raw milk cheese.

But the beef and milk are grass-fed, the pork and poultry are pastured, and the fats— from lard to coconut oil— are unrefined.

Milk, cream, and butter are grass-fed and raw. I relish the rich, unfashionable cuts you never see in "heart-healthy" diets,

such as liver and bone marrow— just as our Stone Age ancestors did. I don't buy low-fat versions of anything. Foods should

be eaten with the fats they come with: whole milk, chicken with skin.

All this real food is good for you. How?

•

Grass-fed beef

is rich in beta-carotene and vitamin E (both fight heart disease and cancer) and CLA, the anticancer fat.

•

Grass-fed milk, cream, butter, and cheese

are rich in vitamins A and D, omega-3 fats, and CLA. Butter contains butyric acid, another fat that fights cancer and infections.

•

Pastured pork and lard

are rich in antimicrobial fats and the monounsaturated fat oleic acid— the same fat in olive oil, which reduces LDL.

•

Pastured eggs

are rich in vitamins A and D. They contain omega-3 fats, which prevent obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and depression. Egg

yolks contain lecithin, which helps metabolize cholesterol.

Cholesterol.

This word alone can stop a story about food in its tracks. The thought of rich, sweet cream has barely taken shape before

the evil ingredient cholesterol flutters by, landing smack-dab in the worry corner of the brain to spoil the reverie. I know

what you're thinking.

Aren't saturated fats and cholesterol

dangerous?

I don't think so.

Let's first agree that Americans are right to be worried about diet and health. Since 1900, once-rare conditions— obesity,

diabetes, and heart disease— have become rampant. These three are known as the diseases of civilization, because for most

of human history they were all but unheard of. (Three million years ago, if you were obese or diabetic or your heart failed,

you would soon be dead.) In the United States today, obesity, diabetes, and heart disease are chronic diseases. They can be

deadly, but just as often, they're a condition people live with, thanks to a combination of drugs, surgery, and diminished

quality of life— as in "I'm too fat and out of breath to play catch with my dog." People with type 2 diabetes survive on insulin

injections. In 1950, most heart attacks were fatal. But today, thanks to major medical advances, more Americans with chronic

heart disease are living longer. Certainly, enabling people to live with chronic disease is a sign of progress. Preventing

disease is another— the one that interests me.

The reader might object that life in the Stone Age was different. For the hunter-gatherer couple, it was nasty, brutish, and

short; he might be gored by a mastodon and she was apt to bleed to death while giving birth. We, on the other hand, live much

longer, with ample time to grow old and to develop degenerative diseases. How do we know the meat-loving hunter-gatherers

would not have keeled over from hardened arteries, too, had they managed to survive to sixty-five?

Good question. Loren Cordain, an expert in Stone Age diets, looked into this one. In most hunter-gatherer groups, 10 to 20

percent are sixty years or older— and in fine health. "These elderly people have been shown to be generally free of the signs

and symptoms of chronic disease (obesity, high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels) that universally afflict the elderly

in western societies," he says. "When these people adopt western [industrial] diets . . . they begin to exhibit signs and

symptoms of 'diseases of civilization.'" So much for the idea that age equals disease.

Let's next agree that the experts are right: diet does affect blood. The study of blood cholesterol and its various subcategories

is getting more sophisticated by the hour, but the conventional wisdom holds that it's better for high-density lipoprotein

(HDL) to be high and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) to be low. Casually known as the "good" and "bad" cholesterol hypothesis,

this idea emerged when it became clear that the number they call "total cholesterol" was a poor— very poor— predictor of heart

disease. Today, most experts believe that low HDL and high LDL are "risk factors" for heart disease, which means the two conditions

are statistically correlated.

But I'm not so sure. There are two important caveats to the rule that high LDL, in particular, is dangerous. The first is

a lesson from Statistics 101: correlation does not necessarily imply cause. In other words, high LDL does not necessarily

cause

heart disease. Instead, it could be a symptom (or

marker,

as experts say) of heart trouble. The second caveat is equally serious: many studies show that high LDL and heart disease

are

not

linked. In 2005, the

Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons

reported that as many as half of the people who have heart disease have normal or "desirable" LDL.

8

Also in 2005, researchers found that older men and women with high LDL live longer.

9

When the rule— high LDL is dangerous— doesn't apply in the elderly or in half of the heart disease cases, the honest scientist

can only conclude one thing: the rule needs a second look. Some cholesterol experts believe the rule needs more than just

tweaking. "There is nothing bad about LDL," says Joel Kauffman, Professor of Chemistry Emeritus at the University of the Sciences

in Philadelphia. "There never was."

10

What might account for the inconsistent findings on LDL and heart disease? First, the link some studies show between high

LDL and heart disease could be explained by oxidation. Research in humans and animals shows that natural LDL is a normal part

of a healthy body, but

oxidized

or damaged LDL is bad news. Perhaps high LDL readings really represent high

oxidized

LDL. Second, does cholesterol really clog arteries? Probably not. According to Kauffman, there is no relationship between

total cholesterol (or LDL) and atherosclerosis. As we'll see later, an amino acid called

homocyste'me,

not cholesterol, actually damages arteries.

Later, we'll look at cholesterol in more detail, but for now, let me say this: I believe the "good" and "bad" cholesterol

story has failed to explain heart disease fully— and worse, it has failed to prevent it. The narrative of evil LDL and knightlike

HDL oversimplifies a complex reality.

What about diet? Other things being equal, does eating foods like butter and eggs, rich in natural cholesterol and natural

saturated fat, have an undesirable effect on blood cholesterol and lead to heart disease? From what I can gather, the answer

is no. High cholesterol and heart disease are rare in cultures where people eat cholesterol-rich foods, including butter,

eggs, and shrimp. The same is true in tropical cultures where they eat saturated coconut oil daily. Studies of traditional

diets are only one reason I eat butter, cream, and coconut oil with impunity. Happily, clinical studies confirm this observation

about saturated fats.

The story about diet and disease is more complicated than just saturated fats and cholesterol, of course. As we'll see, reductionist

thinking is precisely the mistake the experts, who focused everything on cutting fat and cholesterol, made. Traditional diets

are also rich in many other nutrients that

prevent

heart disease, including omega-3 fats in fish and B vitamins. But one thing is clear: if beef and butter were to blame for

heart disease, heart disease would not be new. We've been eating them for too long.

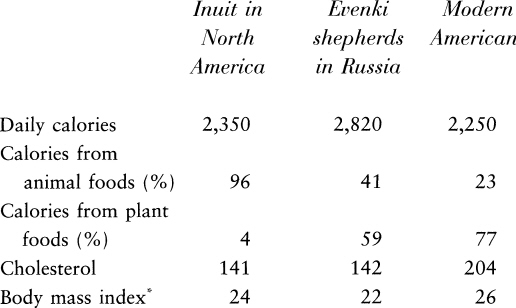

Look at the traditional diets in the accompanying table. They contain more calories, and many more calories from animal foods,

than the modern American diet. Yet Americans are overweight with higher cholesterol levels. Evenki reindeer herders in Russia

derive almost half their calories from meat, almost twice as much as the average American. Yet Evenki men are 20 percent leaner

than American men, with cholesterol levels 30 percent lower.

11

MODERN AMERICAN DIET VERSUS TRADITIONAL DIETS

* A healthy BMI is 18.5-24.9. Above 25 is overweight, and above 30 is obese.

Source: William R. Leonard, "Food for Thought,"

Scientific American,

August 2003, Vol 13, No 2 (updated from the December 2002 issue).

Clearly, the Americans are doing something wrong. Even though we eat fewer calories and more calories from plant foods than

the Inuit and Evenki, we're fat and have "high" cholesterol. The fault may well lie in our diets, but judging from these cases—

and many similar studies of modern hunter-gatherers such as Australian aboriginals— it's unlikely that saturated animal fat

itself

causes unhealthy cholesterol. These lean, healthy people eat a lot of saturated animal fat. Something else must be to blame

for our own poor health.

What might that be? The culprit is industrial foods. Sugar and hydrogenated vegetable oils raise cholesterol and triglycerides.

Eating oxidized— or damaged— cholesterol leads to unhealthy oxidized LDL in the body. The main, dietary source of oxidized

cholesterol is powdered skim milk and powdered eggs, commonly found in processed foods. Finally, other factors are vitally

important. Exercise, for example, keeps you thin and raises HDL. You can bet that Inuit seal hunters and Evenki shepherds

get more exercise than most Americans.

The experts are right: our diet is killing us. But traditional beef, butter, and eggs are not to blame for obesity, diabetes,

and heart disease. The so-called diseases of civilization are caused by the foods of civilization. More accurately, the diseases

of

industrialization

are caused by the foods of

industrialization.

I Am Nursed on the Perfect Food

ON THE DAY I WAS BORN, at home in our big house on 84 Russell Avenue in Buffalo, New York, my mother and I had everything

we wanted. That afternoon she rested comfortably on the couch in our sunny front room, in no particular hurry for anything

to happen, with her family checking in occasionally. March 29, 1971 fell on a Monday, but my father didn't go to work and

my sister and brother stayed home from school. The doctor was just taking off her coat when I arrived on a schedule known

only to my mother and me. Then my mother fed me the perfect food from the perfect container. Later, she fed herself some real

food: mail order organic beef liver from Walnut Acres, one of the pioneering organic brands.

I was a lucky baby. My mother gave me real food in my first hours and nursed me on demand until I stopped asking for fresh

raw milk three years later. If possible, a woman should nurse exclusively for at least one year, or, ideally, until the baby

loses interest. Though it's uncommon today among working women, nursing longer than the usual six or twelve months is natural.

In modern hunter-gatherer societies, nursing for three years is typical and four to six years is not unheard of. UNICEF and

the World Health Organization advise breast-feeding for "two years and beyond."

Breast-feeding cements a profound bond between mother and baby. When things are going well, by all accounts, it's a very nice

sensation. Mothers describe loving, trancelike feelings when nursing, and babies will suckle long after they are full. In

Fresh

Milk: The Secret Life of Breasts,

Fiona Giles collected memories of nursing from young children. "It was comforting and relaxing," said an eight-year-old boy.

"I looked forward to it." A twelve-year-old girl was more blunt: "The word

addictive

comes to mind." An older sibling who had been weaned acted out her own farewell as she watched the new baby nurse. She would

cover her mother's breasts and say, "Bye bye, delicious milk."

Breast milk is our first food, the best food, the ultimate traditional food in all cultures without exception. That's why

nature made nursing satisfying: to encourage mothers and babies to do it.

Because it was designed as the baby's only source of food, breast milk is a complete meal. If the mother is well nourished

on real food, her breast milk will contain just the right amount of protein, fat, carbohydrates, and all the other nutrients

for the growing baby, including essential vitamins, with one notable— and interesting— exception. The milk of all mammals

lacks iron. Moreover, milk contains the protein lactoferrin, which ties up any random iron that does find its way into the

young. There is logic in the missing iron: iron is necessary for the growth of

E. coli,

the most common source of infant diarrhea in all species. A breast-fed baby rarely needs any additional iron before one year;

bottle-fed babies may need iron sooner because infant formula depletes iron. After one year, iron-rich raw liver is often

the first solid food for babies in traditional diets.

Breast milk is not only a complete meal but also a rich one: about 50 percent of its calories come from fat. Indeed, fats

may be the most important thing about breast milk. At the most basic level, fat is essential for the baby's growth and development,

and for assimilating protein and the fat-soluble vitamins A and D, but each particular fat in breast milk also plays an important

role.

The long-chain polyunsaturated omega-3 fats EPA and DHA in mother's milk are vital to eye and brain development in the baby.

Pregnant and nursing women should eat plenty of fish— the only source of fully formed EPA and DHA— and keep eating it. With

each pregnancy, a woman's store of omega-3 fats is depleted. The hungry baby neither knows nor cares whether her mother eats

wild salmon, but simply takes the omega-3 fats she needs to build her own brain.

As we saw earlier, vegans and vegetarians risk deficiency of EPA and DHA. The breast milk of vegan mothers contains less DHA

than nonvegan breast milk.

1

Nursing mothers who do not eat fish are wise to take a generous supplement of flaxseed oil. The body

can

make EPA and DHA from flaxseed oil, but the conversion is uncertain and imperfect. It bears repeating: fish is vastly superior

to plant sources of omega-3 fats.

Most of the fat in breast milk is saturated. The body needs saturated fat to assimilate the polyunsaturated omega-3 fats and

calcium. Mother's milk is a rare source of a saturated fat called lauric acid. Antimicrobial and antiviral, lauric acid is

so critical to the baby's immunity that it must, by law, be added to infant formula; the usual source is coconut oil.

The ample cholesterol in human milk is essential to the developing brain and nervous system. So vital is cholesterol, breast

milk contains a special enzyme to ensure the baby absorbs it fully.

2

Humans make cholesterol in the liver and brain, but infants and children do not make enough cholesterol for health. Thus

the American Dietetic Association says the diets of children under two must include cholesterol.

3

Many other factors in breast milk boost the baby's immunity, an essential shield in its new, germ-filled world. White blood

cells, sugars called oligosaccharides, and lactoferrin fight bacteria and viruses. (Lactoferrin from human milk is patented

for use in killing

E. coli

in the meatpacking industry.) Mother's milk contains all five of the major antibodies, especially IgA, which is found throughout

the human digestive and respiratory systems and protects tissues from pathogens.

4

Babies don't begin to make their own IgA for weeks.

In one of nature's many elegant efficiencies, the antibodies in breast milk are targeted to the pathogens in the mother and

baby's immediate environment; they are tailor-made for the baby. Dr. Jack Newman, a breast-feeding consultant to UNICEF, says

researchers can't explain "how the mother's immune system knows to make antibodies against only pathogenic and not normal

bacteria, but whatever the process may be, it favors the establishment of 'good bacteria' in a baby's gut."

BREAST MILK: A COMPLETE MEAL

• Complete protein and carbohydrate (for growth)

• Saturated lauric acid (to fight infection)

• Polyunsaturated EPA and DHA (for the brain and eyes)

• Cholesterol (for brain and nerves)

• Many immune factors (to fight infections)

• Beneficial bacteria (for digestion)

Breast milk is the most important food a mother will ever feed her baby. A convincing number of studies confirm that babies

who drink this perfect food tend to have better immunity and digestion, lower mortality, and higher IQ than formula-fed infants.

They typically have lower rates of hospital admissions, pneumonia, stomach flu, ear and urinary tract infections, and diarrhea

than bottle-fed babies. In later life, breast-fed babies often have lower blood pressure and cholesterol, and extra protection

against juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, allergies, respiratory infections, eczema, immune system cancers such as lymphoma,

Crohn's disease, diabetes, stroke, and heart disease. Breast-fed babies are less likely to be obese when they grow up, possibly

because breast milk is rich in the protein adiponectin. Adiponectin lowers blood sugar and affects how the body burns fat.

Low levels of adiponectin are linked to obesity, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease.

Some women find that breast-feeding is not as easy as it looks in those lovely paintings of Madonna and Child. For many understandable

reasons, mother and baby may find nursing difficult, painful, or in extreme cases impossible. If nursing isn't right for you

and your baby, choose a formula with care. Even with the best intentions, it hasn't been easy for scientists to duplicate

the properties of breast milk, which contains more than three hundred known ingredients and probably still more yet to be

identified. Most formula contains a mere forty ingredients, and often the main ingredient is sugar. In the United States,

most infant formula contains no long-chain polyunsaturated omega-3 fats, an unconscionable omission given their vital role

in the eyes and brain. The World Health Organization and the European Union both recommend omega-3 fats for babies; infant

formula with DHA is widely available in Europe and Asia.

Soy-based formula and low-fat diets are particularly unwise for babies and children. As we'll see later, soy is far too rich

in estrogens. Low-fat diets cause stunted growth, learning disabilities, interrupted sexual development, and the syndrome

seen in the babies of malnourished vegan and vegetarian mothers, "failure to thrive," which is marked by slow growth and lethargy.

5

The best substitute for breast milk is made from grass-fed, raw whole milk, supplemented with live yogurt cultures and gelatin

(for digestion), coconut oil (for immunity), and cod-liver oil (for the eye and brain).

6

There are also human milk banks for special cases, such as premature babies and those who are allergic to formulas. Throughout

history, women, including wet nurses, have provided milk for infants whose own mothers were unwilling or unable to do so.

At the Mother's Milk Bank in Austin, Texas, potential donors are carefully screened with blood tests, and donated milk is

pasteurized and tested before being fed to babies.

Traditional societies provide advice and assistance to nursing mothers, usually from older relatives or experienced local

women. The contemporary equivalent of this support network is La Leche League, an excellent and friendly source of practical

and scientific knowledge about breast-feeding. If you are nursing and run into difficulty, or if you feel lonely or discouraged,

try calling these modern-day wise women. They know all about cracked and tender nipples— and your baby will thank you one

day.

I Remember Milking Mabel the Cow

WHEN I WAS TWO YEARS OLD, we moved to the Newcombs' farm in Fairfax County, Virginia, and thus began our relationship with

a long line of family cows. There was a red and white Hereford named Katy, a gentle black Angus called Steady Teddy, and then

the milk cows: a Guernsey named Emma, who slipped out one evening and was never heard from again, and a Jersey called Tai

Tai— an honorific akin to "Mrs." in Mandarin. Later, when we moved to our own farm in Loudoun County, we bought Mabel, a chocolate-colored

Jersey. I'm afraid her character didn't conform to the stereotype of the docile cow. My brother, Charles, remembers that "Mabel

was often irritated with us."

By then I was nine or ten, and milking was one of my regular chores. On my night to milk, I'd bring Mabel into the barn from

the pasture, put her in the stanchion, and give her a little grain while I washed her udder. Then I'd sit on a wooden stool

my brother had helped me build and begin to milk, making a ring with my thumb and forefinger and squeezing the teat from the

top down, one finger at a time, first one hand, then the other.

There is a pleasant, lulling rhythm to milking. Even now the sounds are vivid: Mabel's noisy chewing and breathing, the soft

rustling as the chickens settled in for the night. At first, when the bucket is empty, the milk goes "ping" as it hits the

tin. As the pail fills up, each squirt meets the foamy liquid and the pitch drops. In the summer, her tail— called a

switch

in dairy lore— might miss the flies on her flank and sting my face. With Mabel, there was also a good chance she'd lose her

poise and kick the bucket over or step right in it. You had to whisk the bucket away.

Before long her bag was loose and empty, and there were a couple of gallons of milk. If she'd been scratched by brambles,

I rubbed her udder with a miraculous salve called Bag Balm, made in Lyndonville, Vermont, since 1899. (I still use it on my

own cuts and scratches.) I carried the milk across the footbridge to the house and strained it through a striped pink cloth

into glass gallon jars. We wrote the date, plus AM or PM, on masking tape and stuck it to the jar. That was it.

Going to school smelling of cow was mortifying, and when I had to milk in the morning I always took my shower afterward. I

knew we weren't supposed to

sell

raw milk— after we put an ad in the paper, two friendly women from the state came around to tell us to keep it quiet— but

was ignorant about why it was better than supermarket milk. The jars of milk in the fridge were like the wheat berries on

the shelves: embarrassing.

Eventually the burden of daily milking grew tedious, and we sold Mabel

to

a local man, luring her into his truck with sweet corn, and we never kept a cow again. It seems sad now. Having visited dairy

farms small and large, tasted industrial and real milk side by side, and learned a bit about how butter and cheese are made,

I begin to grasp that having more fresh milk and cream than we could drink was a luxury.

Historically, milk was more than a luxury; it was critically important in the diet. For peasants, the cow kept the grocery

bill down and the doctor away. With her ability to convert inedible grass into milk and cream, the cow was at the center of

the domestic economy. Rich in protein, fat, calcium, and B vitamins, milk was known as "white meat," capable of transforming

an inadequate diet of bread and potatoes into a passable one, especially for children. In

cucina

povera

(peasant cooking), vegetables are often soaked in milk before roasting.

A cow needs nothing more than a patch of grass, but most European peasants were too poor to own land, and for centuries they

grazed animals on common land. In Britain and elsewhere, the gradual loss of access to the commons in the late eighteenth

century was catastrophic for peasants, who were no longer able to keep cattle for milk and meat. The British historian J.

M. Neeson describes "the stubborn memory of roast beef and milk" and their "swift disappearance" from the diet of the poor

after the loss of grazing rights.

7

In 1786, the cleric H. J. Birch wrote that butter was too dear for his Danish parishioners. They made do with bread crusts,

beer, and cabbage boiled without meat. When "cottagers receive not the smallest patch of land or grazing for cows or sheep,

and are not even entitled to keep as much as a couple of geese on the common . . . then poverty and need reach dire extremes;

then cottagers begin to beg— people who have never begged before, and never thought of begging."

8