Red Sky at Sunrise: Cider with Rosie, As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, A Moment of War (10 page)

Authors: Laurie Lee

‘… You know that boy from the Dairy, Marge – the one they call Barnacle Boots? Well, he asked me to go to Spot’s with him. I told him to run off home.’

‘No, you never!’

‘I certainly did. I said I don’t go to no pictures with butter-wallopers. You should have seen his face…’

‘Harry Lazbury smells of chicken-gah. I had to move me desk.’

‘Just hark who’s talking. Dainty Dick.’

‘I’ll never be ready by Sunday…’

‘I’ve found a lovely snip for my animal page – an old seal – look girls, the expression!…’

‘So I went round ’ere, and down round ’ere, and he said fie so I went ’ack, ’ack…’

‘What couldn’t I do to a nice cream slice…’

‘Charlie Revell’s had ‘is ears syringed…’

‘D’you remember, Doth, when we went to Spot’s, and they said Children in Arms Not Allowed, and we walked little Tone right up the steps and he wasn’t even two…’

Marge gave her silky, remembering laugh and looked fondly across at Tony. The fire burned clear with a bottle-green light. Their voices grew low and furry. A farm-dog barked far across the valley, fixing the time and distance exactly. Warned by the dog and some hooting owls, I could sense the night valley emptying, stretching in mists of stars and water, growing slowly more secret and late.

The kitchen, warm and murmuring now, vibrated with rosy darkness. My pencil began to wander on the page, my eyes to cloud and clear. I thought I’d stretch myself on the sofa – for a while, for a short while only. The girls’ muted chatter went on and on; I struggled to catch the drift. ‘Sh!… Not now… When the boys are in bed… You’ll die when you hear… Not now…’

The boards on the ceiling were melting like water. Words broke and went floating away. Chords of smooth music surged up in my head, thick tides of warmth overwhelmed me, I was drowning in languors of feathered seas, spiralling cosily down…

Once in a while I was gently roused to a sound amplified by sleep; to the fall of a coal, the sneeze of the cat, or a muted exclamation. ‘She couldn’t have done such a thing… She did…’ ‘Done what?… What thing?… Tell, tell me…’ But helpless I glided back to sleep, deep in the creviced seas, the blind waters stilled me, weighed me down, the girls’ words floated on top. I lay longer now, and deeper far; heavier weeds were falling on me…

‘Come on, Loll. Time to go to bed. The boys went up long ago.’ The whispering girls bent over me; the kitchen returned upside down. ‘Wake up, lamb . .. He’s whacked to the wide. Let’s try and carry him up.’

Half-waking, half-carried, they got me upstairs. I felt drunk and tattered with dreams. They dragged me stumbling round the bend in the landing, and then I smelt the sweet blankets of bed.

It was cold in the bedroom; there were no fires here. Jack lay open-mouthed, asleep. Shivering, I swayed while the girls undressed me, giggling around my buttons. They left me my shirt and my woollen socks, then stuffed me between the sheets.

Away went the candle down the stairs, boards creaked and the kitchen door shut. Darkness. Shapes returning slow. The window a square of silver. My bed-half was cold – Jack hot as a bird. For a while I lay doubled, teeth-chattering, blowing, warming against him slowly.

‘Keep yer knees to yerself,’ said Jack, turning over. He woke. ‘Say, think of a number!’

‘’Leven-hundered and two,’ I groaned, in a trance.

‘Double it,’ he hissed in my ear.

Double it… Twenny-four hundered and what? Can’t do it. Something or other… A dog barked again and swallowed a goose. The kitchen still murmured downstairs. Jack quickly submerged, having fired off his guns, and began snorkling away at my side. Gradually I straightened my rigid limbs and hooked all my fingers together. I felt wide awake now. I thought I’d count to a million. ‘One, two…” I said; that’s all.

Our house was seventeenth-century Cotswold, and was handsome as they go. It was built of stone, had hand-carved windows, golden surfaces, moss-flaked tiles, and walls so thick they kept a damp chill inside them whatever the season or weather. Its attics and passages were full of walled-up doors which our fingers longed to open – doors that led to certain echoing chambers now sealed off from us for ever. The place had once been a small country manor, and later a public beerhouse; but it had decayed even further by the time we got to it, and was now three poor cottages in one. The house was shaped like a T, and we lived in the down-stroke. The top-stroke – which bore into the side of the bank like a rusty expended shell – was divided separately among two old ladies, one’s portion lying above the other’s.

Granny Trill and Granny Wallon were rival ancients and lived on each other’s nerves, and their perpetual enmity was like mice in the walls and absorbed much of my early days. With their sickle-bent bodies, pale pink eyes, and wild wisps of hedgerow hair, they looked to me the very images of witches and they were also much alike. In all their time as such close neighbours they never exchanged a word. They communicated instead by means of boots and brooms – jumping on floors and knocking on ceilings. They referred to each other as “Er-Down-Under’ and “Er-Up-Atop, the Varmint’; for each to the other was an airy nothing, a local habitation not fit to be named.

‘Er-Down-Under, who lived on our level, was perhaps the smaller of the two, a tiny white shrew who came nibbling through her garden, who clawed squeaking with gossip at our kitchen window, or sat sucking bread in the sun; always mysterious and self-contained and feather-soft in her movements. She had two names, which she changed at will according to the mood of her day. Granny Wallon was her best, and stemmed, we were told, from some distinguished alliance of the past. Behind this crisp and trotting body were certainly rumours of noble blood. But she never spoke of them herself. She was known to have raised a score of children. And she was known to be very poor. She lived on cabbage, bread, and potatoes – but she also made excellent wines.

Granny Wallon’s wines were famous in the village, and she spent a large part of her year preparing them. The gathering of the ingredients was the first of the mysteries. At the beginning of April she would go off with her baskets and work round the fields and hedges, and every fine day till the end of summer would find her somewhere out in the valley. One saw her come hobbling home in the evening, bearing her cargoes of crusted flowers, till she had buckets of cowslips, dandelions, elder-blossom crammed into every corner of the house. The elder-flower, drying on her kitchen floor, seemed to cover it with a rancid carpet, a crumbling rime of grey-green blossom fading fast in a dust of summer. Later the tiny grape-cluster of the elderberry itself would be seething in purple vats, with daisies and orchids thrown in to join it, even strands of the dog-rose bush.

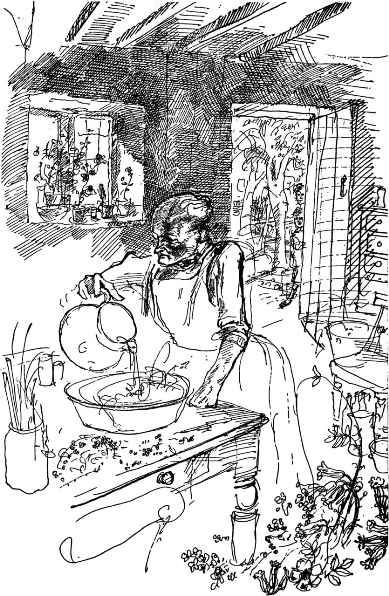

What seasons fermented in Granny Wallon’s kitchen, what summers were brought to the boil, with limp flower-heads piled around the floor holding fast to their clotted juices – the sharp spiced honey of those cowslips first, then the coppery reeking dandelion, the bitter poppy’s whiff of powder, the cat’s-breath, death-green elder. Gleanings of days and a dozen pastures, strip-pings of lanes and hedges – she bore them home to her flag-tiled kitchen, sorted them each from each, built up her fires and loaded her pots, and added her sugar and yeast. The vats boiled daily in suds of sugar, revolving petals in throbbing water, while the air, aromatic, steamy, embalmed, distilled the hot dews and flowery soups and ran the wine down the dripping walls.

And not only flower-heads went into these brews; the old lady used parsnips, too, potatoes, sloes, crab-apples, quinces, in fact anything she could lay her hands on. Granny Wallon made wine as though demented, out of anything at all; and no doubt, if given enough sugar and yeast, could have made a drink out of a box of old matches.

She never hurried or hoarded her wines, but led them gently through their natural stages. After the boiling they were allowed to settle and to work in the cool of the vats. For several months, using pieces of toast, she scooped off their yeasty sediments. Then she bottled and labelled each liquor in turn and put them away for a year.

At last one was ready, then came the day of distribution. A squeak and a rattle would shake our window, and we’d see the old lady, wispily grinning, waving a large white jug in her hand.

‘Hey there, missus! Try this’n, then. It’s the first of my last year’s cowslip.’

Through the kitchen window she’d fill up our cups and watch us, head cocked, while we drank. The wine in the cups was still and golden, transparent as a pale spring morning. It smelt of ripe grass in some far-away field and its taste was as delicate as air. It seemed so innocent, we would swig away happily and even the youngest guzzled it down. Then a curious rocking would seize the head; tides rose from our feet like a fever, the kitchen walls began to shudder and shift, and we all fell in love with each other.

Very soon we’d be wedged, tight-crammed, in the window, waving our cups for more, while our Mother, bright-eyed, would be mumbling gaily:

‘Lord bless you, Granny. Fancy cowsnips and parsney. You must give me the receipt, my dear.’

Granny Wallon would empty the jug in our cups, shake out the last drops on the flowers, then trot off tittering down the garden path, leaving us hugging ourselves in the window.

*

Whatever the small indulgences with which Granny Wallon warmed up her old life, her neighbour, Granny Trill, had none of them. For ‘Er-Up-Atop was as frugal as a sparrow and as simple in her ways as a grub. She could sit in her chair for hours without moving, a veil of blackness over her eyes, a suspension like frost on her brittle limbs, with little to show that she lived at all save the gentle motion of her jaws. One of the first things I noticed about old Granny Trill was that she always seemed to be chewing, sliding her folded gums together in a daylong ruminative cud. I took this to be one of the tricks of age, a kind of slowed-up but protracted feasting. I imagined her being delivered a quartern loaf – say, on a Friday night – then packing the lot into her rubbery cheeks and chewing them slowly through the week. In fact, she never ate bread at all – or butter, or meat, or vegetables – she lived entirely on tea and biscuits, and on porridge sent up by the Squire.

Granny Trill had an original sense of time which seemed to obey some vestigial pattern. She breakfasted, for instance, at four in the morning, had dinner at ten, took tea at two-thirty, and was back in her bed at five. This regime never varied either winter or summer, and belonged very likely to her childhood days when she lived in the woods with her father. To me it seemed a monstrous arrangement, upsetting the roots of order. But Granny Trill’s time was for God, or the birds, and although she had a clock she kept it simply for the tick, its hands having dropped off years ago.

In contrast to the subterranean, almost cavernous life which Granny Wallon lived down under, Granny Trill’s cottage door was always open and her living-room welcomed us daily. Not that she could have avoided us anyway, for she lay at our nimble mercy. Her cottage was just outside our gate and there were geraniums in pots round the door. Her tiny room opened straight on to the bank and was as visible as a last year’s bird’s-nest. Smells of dry linen and tea-caddies filled it, together with the sweeter tang of old flesh.

‘You at home, Granny Trill? You in there, Gran?’

Of course – where else would she be? We heard her creaking sigh from within.

‘Well, I’ll be bound. That you varmints again?’