Red Sky at Sunrise: Cider with Rosie, As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, A Moment of War (13 page)

Authors: Laurie Lee

The old lady at last had a lucid moment and saw the stranger sitting beside her. ‘Who’s this?’ she demanded of her hovering daughter. The girl leaned over the bed. ‘It’s all right, Mother,’ said the daughter distinctly. ‘It’s only a police-station gentleman. He hasn’t come to make any trouble. He just wants to hear about the watch.’

The old lady gave the stranger a sharp clear look and uttered not another word; she just leaned back on the pillow, closed her lips and eyes, folded her hands, and died. It was the end of the weakness that had endangered her sons; and the dark-suited stranger knew it. He rose to his feet, put his notebook in his pocket, and tiptoed out of the room. This old and wandering dying mind had been their final chance. No other leads appeared after that, and the case was never solved.

But the young men who had gathered in that winter ambush continued to live among us. I saw them often about the village: simple jokers, hard-working, mild – the solid heads of families. They were not treated as outcasts, nor did they appear to live under any special stain. They belonged to the village and the village looked after them. They are all of them dead now anyway.

Grief or madness were not so private, though they were kept within the village, playing themselves out before our eyes to the accompaniment of lowered voices. There was the case of Miss Flynn, the Ashcomb suicide, a solitary off-beat beauty, whose mute, distressed, life-abandoned image remains with me till this day.

Miss Flynn lived up on the other side of the valley in a cottage which faced the Severn, a cottage whose rows of tinted windows all burst into flame at sundown. She was tall, consumptive, and pale as thistledown, a flock-haired pre-Raphaelite stunner, and she had a small wind-harp which played tunes to itself by swinging in the boughs of her apple trees. On walks with our Mother we often passed that way, and we always looked out for her. When she saw strangers coming she skipped at the sight of them – into her cellar or into their arms. Mother was evasive when we asked questions about her, and said, ‘There are others more wicked, poor soul.’

Miss Flynn liked us boys, and gave us apples and stroked our hair with her long yellow fingers. We liked her too, in an eerie way – her skipping, her hair, her harp in the trees, her curious manners of speech. Her beauty for us was also remarkable, there was no one like her in the district; her long, stone-white and tapering face seemed as cool as a churchyard angel.

I remember the last time we passed her cottage, our eyes cocked as usual for her. She was sitting behind the stained-glass window, her face brooding in many colours. Our Mother called brightly; ‘Yoo-hoo, Miss Flynn! Are you home? How you keeping, my dear?’

Miss Flynn came out with a skip to the door, stared down at her hands, then at us.

‘Such cheeky boys,’ I heard her say. ‘The image of Morgan they are.’ She lifted one knee and pointed her toe. ‘I’ve been bad, Mrs Er,’ she said.

She came swaying towards us, twisting her hair with her fingers and looking white as a daylight moon. Our Mother made a clucking, sympathetic sound, and said the west wind was bad for the nerves.

Miss Flynn embraced Tony with a kind of abstract passion and stared hard over our heads at the distance.

‘I’ve been bad, Mrs Er – for the things I must do. It’s my mother again, you know. I’ve been trying to keep her sick spirit from me. She don’t let me alone at nights.’

Quite soon we were hurried off down the lane, although we were loath to go. ‘The poor, poor soul,’ Mother sighed to herself; ‘and she half gentry, too…’

A few mornings later we were sitting round the kitchen, waiting for Fred Bates to deliver the milk. It must have been a Sunday because the breakfast was spoilt; and on weekdays that didn’t matter. Everybody was grumbling; the porridge was burnt, and we hadn’t yet had any tea. When Fred came at last he was an hour and a half late, and he had a milk-wet look in his eyes.

‘Where were you, Fred Bates?’ our sisters demanded; he’d never been late before. He was a thin, scrubby lad in his middle teens, with a head like a bottle-brush. But the cat didn’t coil round his legs this morning, and he made no reply to the girls. He just ladled us out our usual jugful and kept sniffing and muttering ‘God dammit’.

‘What’s up then, Fred?’ asked Dorothy.

‘Ain’t nobody told you?’ he asked. His voice was hollow, amazed, yet proud, and it made the girls sit up. They dragged him indoors and poured him a cup of tea and forced him to sit down a minute. Then they all gathered round him with gaping eyes, and I could see they had sniffed an occurrence.

At first Fred could only blow hard on his tea and mutter,

‘Who’d

a thought it?’ But slowly, insidiously, the girls worked on him, and in the end they got his story…

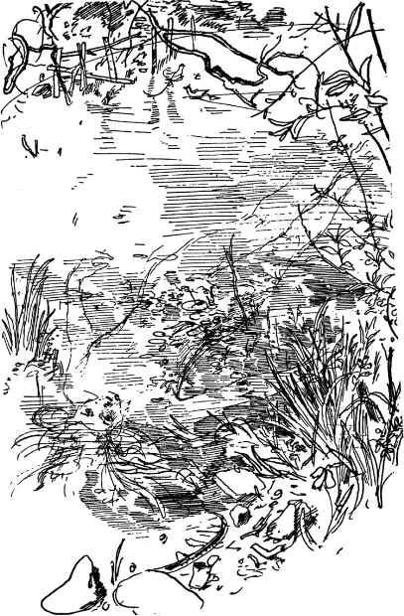

He’d been coming from milking; it was early, first light, and he was just passing Jones’s pond. He’d stopped for a minute to chuck a stone at a rat – he got tuppence a tail when he caught one. Down by the lily-weeds he suddenly saw something floating. It was spread out white in the water. He’d thought at first it was a dead swan or something, or at least one of Jones’s goats. But when he went down closer, he saw, staring up at him, the white drowned face of Miss Flynn. Her long hair was loose – which had made him think of a swan – and she wasn’t wearing a stitch of clothes. Her eyes were wide open and she was staring up through the water like somebody gazing through a window. Well, he’d got such a shock he dropped one of his buckets, and the milk ran into the pond. He’d stood there a bit, thinking, ‘That’s Miss Flynn’; and there was no one but him around. Then he’d run back to the farm and told them about it, and they’d come and fished her out with a hay-rake. He’d not waited to see any more, not he; he’d got his milk to deliver.

Fred sat for a while, sucking his tea, and we gazed at him with wonder. We all knew Fred Bates, we knew him well, and our girls often said he was soppy; yet only two hours ago, and only just down the lane, he’d seen drowned Miss Flynn with no clothes on. Now he seemed to exude a sort of salty sharpness so that we all wished to touch and taste him; and the excited girls tried to hold him back and make him go through his story again. But he finished his tea, sniffed hard, and left us, saying he’d still got his milk-round to do.

The news soon spread around the village, and women began to gather at their gates.

‘Have you heard?’

‘No. What?’

‘About poor Miss Flynn… Been and drowned herself down in the pond.’

‘You just can’t mean it!’

‘Yes. Fred Bates found her.’

‘Yes – he just been drinking tea in our kitchen.’

‘I can’t believe it. I only saw her last week.’

‘I know: I saw her just yesterday. I said, “Good morning, Miss Flynn”; and she said, “Good morning, Mrs Ayres,” – you know, like she always did.’

‘But she was down in the town, only Friday it was! I saw her in the Home-and-Colonial.’

‘Poor, sad creature – whatever made her do it?’

‘Such a lovely face she had.’

‘So good to our boys. She was kindness itself. To think of her lying there.’

‘She had a bit of a handicap, so they say.’

‘You mean about those fellows?’

‘No, more’n that.’

‘What was it?’

‘Ssssh!’

‘Well, not everyone knows, of course…’

Miss Flynn was drowned. The women looked at me listening. I stole off and ran down the lane. I was dry with excitement and tight with dread; I just wanted to see the pond. A group of villagers, including my sisters, stood gaping down at the water. The pond was flat and green and empty, and a smudge of milk clung to the reeds. I hid in the rushes, hoping not to be seen, and stared at that seething stain. This was the pond that had choked Miss Flynn. Yet strangely, and not by accident. She had come to it naked, alone in the night, and had slipped into it like a bed; she lay down there, and drew the water over her, and drowned quietly away in the reeds. I gazed at the lily roots coiled deep down, at the spongy weeds around them. That’s where she lay, a green foot under, still and all night by herself, looking up through the water as though through a window and waiting for Fred to come by. One of my knees began to quiver; it was easy to see her there, her hair floating out and her white eyes open, exactly as Fred Bates had found her. I saw her clearly, slightly magnified, and heard her vague dry voice: ‘I’ve been bad, Mrs Er. It’s my mother’s spirit. She won’t let me bide at night…’

The pond was empty. She’d been carried home on a hurdle, and the women had seen to her body. But for me, as long as I can remember, Miss Flynn remained drowned in that pond.

As for Fred Bates, he enjoyed for a day a welcome wherever he went. He repeated his story over and over again and drank cups of tea by the dozen. But his fame turned bad, very suddenly; for a more sinister sequel followed. The very next day, on a visit to Stroud, he saw a man crushed to death by a wagon.

‘Twice in two days,’ the villagers said. ‘He’ll see the Devil next.’

Fred Bates was avoided after that. We crossed roads when we saw him coming. No one would speak to him or look him in the eyes, and he wasn’t allowed to deliver milk any more. He was sent off instead to work alone in a quarry, and it took him years to re-establish himself.

*

The murder and the drowning were long ago, but to me they still loom large; the sharp death-taste, tooth-edge of violence, the yielding to the water of that despairing beauty, the indignant blood in the snow. They occurred at a time when the village was the world and its happenings all I knew. The village in fact was like a deep-running cave still linked to its antic past, a cave whose shadows were cluttered by spirits and by laws still vaguely ancestral. This cave that we inhabited looked backwards through chambers that led to our ghostly beginnings; and had not, as yet, been tidied up, or scrubbed clean by electric light, or suburbanized by a Victorian church, or papered by cinema screens.

It was something we just had time to inherit, to inherit and dimly know – the blood and beliefs of generations who had been in this valley since the Stone Age. That continuous contact has at last been broken, the deeper caves sealed off for ever. But arriving, as I did, at the end of that age, I caught whiffs of something old as the glaciers. There were ghosts in the stones, in the trees, and the walls, and each field and hill had several. The elder people knew about these things and would refer to them in personal terms, and there were certain landmarks about the valley – tree-clumps, corners in woods – that bore separate, antique, half-muttered names that were certainly older than Christian. The women in their talk still used these names which are not used now any more. There was also a frank and unfearful attitude to death, and an acceptance of violence as a kind of ritual which no one accused or pardoned.

In our grey stone village, especially in winter, such stories never seemed strange. When I sat at home among my talking sisters, or with an old woman sucking her jaws, and heard the long details of hapless suicides, of fighting men loose in the snow, of witch-doomed widows disembowelled by bulls, of child-eating sows, and so on – I would look through the windows and see the wet walls streaming, the black trees bend in the wind, and I saw these things happening as natural convulsions of our landscape, and though dry-mouthed, I was never astonished.

Being so recently born, birth had no meaning; it was the other extreme that enthralled me. Death was absorbing, and I saw much of it; it was my childhood’s continuous fare. Somebody else had gone, they had gone in the night, and nobody tried to hide it. Old women, bright-eyed, came carrying the news; the corpse was praised and buried; while Mother and the girls at their kitchen chorus went over the final hours. ‘The poor old thing. She fought to the last. She didn’t have the strength left in her.’ They wept easily, sniffing, and healthily flushed; they could have been mourning the death of a dog.

Winter, of course, was the worst time for the old ones. Then they curled up like salted snails. We called one Sunday on the old Davies couple who lived along by the shop. It had been a cold wet January, a marrow-bone freezer, during which three old folk, on three successive Saturdays, had been carried off to their graves. Mr and Mrs Davies were ancient too, but they had a stubborn air of survival; and they used to watch each other, as I remember, with the calculating looks of card-players. This morning the women began to discuss the funerals, while we boys sat down by the fire. Mrs Davies was jaunty, naming each of the mourners and examining their bills of health. She rocked her white head, shot her husband a glance, and said she wondered who would be next.