Red Sky at Sunrise: Cider with Rosie, As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, A Moment of War (16 page)

Authors: Laurie Lee

The three or four years Mother spent with my father she fed on for the rest of her life. Her happiness at that time was something she guarded as though it must ensure his eventual return. She would talk about it almost in awe, not that it had ceased but that it had happened at all.

‘He was proud of me then. I could make him laugh. “Nance, you’re a killer,” he’d say. He used to sit on the doorstep quite helpless with giggles at the stories and things I told him. He admired me too; he admired my looks; he really loved me, you know. “Come on, Nance,” he’d say. ‘Take out your pins. Let your hair down – let’s see it shine!’ He loved my hair; it had gold lights in it then and it hung right down my back. So I’d sit in the window and shake it over my shoulders – it was so heavy you wouldn’t believe – and he’d twist and arrange it so that it caught the sun, and then sit and just gaze and gaze…

‘Sometimes, when you children were all in bed, he’d clear all his books away – “Come on, Nance,” he’d say, “I’ve had enough of them. Come and sing us a song!” We’d go to the piano, and I’d sit on his lap, and he’d play with his arms around me. And I’d sing him “Killarney” and “Only a Rose”. They were both his favourites then…’

When she told us these things it was yesterday and she held him again in her enchantment. His later scorns were stripped away and the adored was again adoring. She’d smile and look up the weed-choked path as though she saw him coming back for more.

But it was over all right, he’d gone for good, we were alone and that was that. Mother struggled to keep us clothed and fed, and found it pretty hard going. There was never much money, perhaps just enough, the few pounds that Father sent us; but it was her own muddlehead that Mother was fighting, her panic and innocence, forgetfulness, waste, and the creeping tide of debt. Also her outbursts of wayward extravagance which splendidly ignored our needs. The rent, as I said, was only 3s. 6d. a week, but we were often six months behind. There would be no meat at all from Monday to Saturday, then on Sunday a fabulous goose; no coal or new clothes for the whole of the winter, then she’d take us all to the theatre; Jack, with no boots, would be expensively photographed, a new bedroom suite would arrive; then we’d all be insured for thousands of pounds and the policies would lapse in a month. Suddenly the iron-frost of destitution would clamp down on the house, to be thawed out by another orgy of borrowing, while harsh things were said by our more sensible neighbours and people ran when they saw us coming.

In spite of all this, Mother believed in good fortune, and especially in newspaper competitions. She was also convinced that if you praised a firm’s goods they would shower you with free samples and money. She was once paid five shillings for such a tribute which she had addressed to a skin-food firm. From then on she bombarded the market with letters, dashing off several each week. Ecstatically phrased and boasting miraculous cures, they elegantly hinted at new dawns opened up because of, or salvations due only to: headache-powders, limejuice-bottlers, corset-makers, beef-extractors, sausage-stuffers, bust-improvers, eyelash-growers, soap-boilers, love-mongerers, statesmen, corn-plasterers, and kings. She never got another penny from any of these efforts; but such was her style, her passion and conviction, that the letters were often printed. She had bundles of clippings lying all over the house, headed ‘Grateful Sufferer’ or ‘After Years of Torture’ or ‘I Used to Groan Myself to Sleep till I Stumbled on Your Ointment’… She used to read them aloud with a flush of pride, quite forgetting their original purpose.

Deserted, debt-ridden, flurried, bewildered, doomed by ambitions that never came off, yet our Mother possessed an indestructible gaiety which welled up like a thermal spring. Her laughing, like her weeping, was instantaneous and childlike, and switched without warning – or memory. Her emotions were entirely without reserve; she clouted you one moment and hugged you the next – to the ruin of one’s ragged nerves. If she knocked over a pot, or cut her finger she let out a blood-chilling scream – then forgot about it immediately in a hop and skip or a song. I can still seem to hear her blundering about the kitchen: shrieks and howls of alarm, an occasional oath, a gasp of wonder, a sharp command to things to stay still. A falling coal would set her hair on end, a loud knock make her leap and yell, her world was a maze of small traps and snares acknowledged always by cries of dismay. One couldn’t help jumping in sympathy with her, though one learned to ignore these alarms. They were, after all, no more than formal salutes to the devils that dogged her heels.

Often, when working and not actually screaming, Mother kept up an interior monologue. Or she would absentmindedly pick up your last remark and sing it back at you in doggerel. ‘Give me some tart,’ you might say, for instance. ‘Give you some tart? Of course… Give me some tart! O give me your heart! Give me your heart to keep! I’ll guard it well, my pretty Nell, As the shepherd doth guard his sheep, tra-la…’

Whenever there was a pause in the smashing of crockery, and Mother was in the mood, she would make up snap verses about local characters that could stab like a three-pronged fork:

Mrs Okey

Makes me choky:

Hit her with a mallet! – croquet.

This was typical of their edge, economy, and freedom. Mrs Okey was our local postmistress and an amiable, friendly woman; but my Mother would sacrifice anybody for a rhyme.

Mother, like Gran Trill, lived by no clocks, and unpunctuality was bred in her bones. She was particularly offhand where buses were concerned and missed more than she ever caught. In the free-going days when only carrier-carts ran to Stroud she would often hold them up for an hour, but when the motor-bus started she saw no difference and carried on in the same old way. Not till she heard its horn winding down from Sheepscombe did she ever begin to get ready. Then she would cram on her hat and fly round the kitchen with habitual cries and howls.

‘Where’s my gloves? Where’s my handbag? Damn and cuss – where’s my shoes? You can’t find a thing in this hole! Help me, you idiots – don’t just jangle and jarl – you’ll all make me miss it, I know. Scream! There it comes! – Laurie, run up and stop it. Tell ‘em I won’t be a minute…’

So I’d tear up the bank, just in time as usual, while the packed bus steamed to a halt.

‘… Just coming, she says. Got to find her shoes. Won’t be a minute, she says…’

Misery for me; I stood there blushing; the driver honked his horn, while all the passengers leaned out of the windows and shook their umbrellas crossly.

‘Mother Lee again. Lost ‘er shoes again. Come on, put a jerk in it there!’

Then sweet and gay from down the bank would come Mother’s placating voice.

‘I’m coming – yoo-hoo! I Just mislaid my gloves. Wait a second! I’m coming, my dears.’

Puffing and smiling, hat crooked, scarf dangling, clutching her baskets and bags, she’d come hobbling at last through the stinging-nettles and climb hiccuping into her seat…

When neither bus nor carrier-cart were running, Mother walked the four miles to the shops, trudging back home with her baskets of groceries and scattering packets of tea in the mud. When she tired of this, she’d borrow Dorothy’s bicycle, though she never quite mastered the machine. Happy enough when the thing was in motion, it was stopping and starting that puzzled her. She had to be launched on her way by running parties of villagers; and to stop she rode into a hedge. With the Stroud Co-op Stores, where she was a registered customer, she had come to a special arrangement. This depended for its success upon a quick ear and timing, and was a beautiful operation to watch. As she coasted downhill towards the shop’s main entrance she would let out one of her screams; an assistant, specially briefed, would tear through the shop, out the side door, and catch her in his arms. He had to be both young and nimble, for if he missed her she piled up by the police-station.

Our Mother was a buffoon, extravagant and romantic, and was never wholly taken seriously. Yet within her she nourished a delicacy of taste, a sensibility, a brightness of spirit, which though continuously bludgeoned by the cruelties of her luck remained uncrushed and unembittered to the end. Wherever she got it from, God knows – or how she managed to preserve it. But she loved this world and saw it fresh with hopes that never clouded. She was an artist, a light-giver, and an original, and she never for a moment knew it…

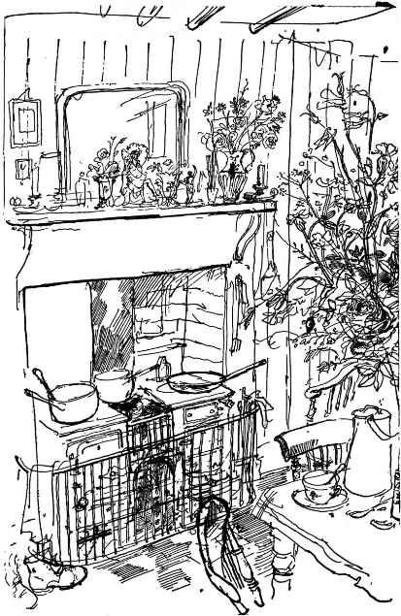

My first image of my Mother was of a beautiful woman, strong, bounteous, but with a gravity of breeding that was always visible beneath her nervous chatter. She became, in a few years, both bent and worn, her healthy opulence quickly gnawed away by her later trials and hungers. It is in this second stage that I remembered her best, for in this stage she remained the longest. I can see her prowling about the kitchen, dipping a rusk into a cup of tea, with hair loose-tangled, and shedding pins, clothes shape-lessly humped around her, eyes peering sharply at some revelation of the light, crying Ah or Oh or There, talking of Tonks or reciting Tennyson and demanding my understanding.

With her love of finery, her unmade beds, her litters of unfinished scrapbooks, her taboos, superstitions, and prudishness, her remarkable dignity, her pity for the persecuted, her awe of the gentry, and her detailed knowledge of the family trees of all the Royal Houses of Europe, she was a disorganized mass of unreconciled denials, a servant girl born to silk. Yet in spite of all this, she fed our oafish wits with steady, imperceptible shocks of beauty. Though she tortured our patience and exhausted our nerves, she was, all the time, building up around us, by the unconscious revelations of her loves, an interpretation of man and the natural world so unpretentious and easy that we never recognized it then, yet so true that we never forgot it.

Nothing now that I ever see that has the edge of gold around it – the change of a season, a jewelled bird in a bush, the eyes of orchids, water in the evening, a thistle, a picture, a poem – but my pleasure pays some brief duty to her. She tried me at times to the top of my bent. But I absorbed from birth, as now I know, the whole earth through her jaunty spirit.

Not until I left home did I ever live in a house where the rooms were clear and carpeted, where corners were visible and window-seats empty, and where it was possible to sit on a kitchen chair without first turning it up and shaking it. Our Mother was one of those obsessive collectors who spend all their time stuffing the crannies of their lives with a ballast of wayward objects. She collected anything that came to hand, she never threw anything away, every rag and button was carefully hoarded as though to lose it would imperil us all. Two decades of newspapers, yellow as shrouds, was the dead past she clung to, the years saved for my father, maybe something she wished to show him… Other crackpot symbols also littered the house: chair-springs, boot-lasts, sheets of broken glass, corset-bones, picture-frames, firedogs, top-hats, chess-men, feathers, and statues without heads. Most of these came on the tides of unknowing, and remained as though left by a flood. But in one thing – old china – Mother was a deliberate collector, and in this had an expert’s eye.

Old china to Mother was gambling, the bottle, illicit love, all stirred up together; the sensuality of touch and the ornament of a taste she was born to but could never afford. She hunted old china for miles around, though she hadn’t the money to do so; haunted shops and sales with wistful passion, and by wheedling, guile, and occasional freaks of chance carried several fine pieces home.

Once, I remember, there was a big auction at Bisley, and Mother couldn’t sleep for the thought of its treasures.

‘It’s a splendid old place,’ she kept telling us. ‘The Delacourt family, you know. Very cultivated they were – or

she

was, at least. It would be a crime not to go and look.’

When the Sale day arrived, Mother rose right early and dressed in her auction clothes. We had a cold scratch breakfast – she was too nervy to cook – then she edged herself out through the door.

‘I shall only be looking. I shan’t buy, of course. I just wanted to see their Spode…’

Guiltily she met our expressionless eyes, then trotted away through the rain…

That evening, just as we were about to have tea, we heard her calling as she came down the bank.

‘Boys! Marge – Doth! I’m home! Come and see!’

Mud-stained, flushed, and just a little shifty, she came hobbling through the gate.

‘Oh, you

should

have been there. Such china and glass. I never saw anything like it. Dealers, dealers all over the place – but I did ‘em all in the eye. Look, isn’t it beautiful? I just had to get it… and it only cost a few coppers.’