Red Sky at Sunrise: Cider with Rosie, As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, A Moment of War (27 page)

Authors: Laurie Lee

Meanwhile, it was as though I had been dipped in hot oil, baked, dried, and hung throbbing on wires. Mysterious senses clicked into play overnight, possessed one in luxuriant order, and one’s body seemed tilted out of all recognition by shifts in its balance of power. It was the time when the thighs seemed to burn like dry grass, to cry for cool water and cucumbers, when the emotions swung drowsily between belly and hands, prickled, hungered, moulded the curves of the clouds; and when to lie face downwards in a summer field was to feel the earth’s thrust go through you. Brother Jack and I grew suddenly more active, always running or shinning up trees, working ourselves into lathers of exhaustion, whereas till then we’d been inclined to indolence. It was not that we didn’t know what was happening to us, we just didn’t know what to do with it. And I might have been shinning up trees to this day if it hadn’t been for Rosie Burdock…

The day Rosie Burdock decided to take me in hand was a motionless day of summer, creamy, hazy, and amber-coloured, with the beech trees standing in heavy sunlight as though clogged with wild wet honey. It was the time of hay-making, so when we came out of school Jack and I went to the farm to help.

The whirr of the mower met us across the stubble, rabbits jumped like firecrackers about the fields, and the hay smelt crisp and sweet. The farmer’s men were all hard at work, raking, turning, and loading. Tall, whiskered fellows forked the grass, their chests like bramble patches. The air swung with their forks and the swathes took wing and rose like eagles to the tops of the wagons. The farmer gave us a short fork each and we both pitched in with the rest…

I stumbled on Rosie behind a haycock, and she grinned up at me with the sly, glittering eyes of her mother. She wore her tartan frock and cheap brass necklace, and her bare legs were brown with hay-dust.

‘Get out a there,’ I said. ‘Go on.’

Rosie had grown and was hefty now, and I was terrified of her. In her cat-like eyes and curling mouth I saw unnatural wisdoms more threatening than anything I could imagine. The last time we’d met I’d hit her with a cabbage stump. She bore me no grudge, just grinned.

‘I got sommat to show ya.’

‘You push off,’ I said.

I felt dry and dripping, icy hot. Her eyes glinted, and I stood rooted. Her face was wrapped in a pulsating haze and her body seemed to flicker with lightning.

‘You thirsty?’ she said.

‘I ain’t, so there.’

‘You be,’ she said. ‘C’mon.’

So I stuck the fork into the ringing ground and followed her, like doom.

We went a long way, to the bottom of the field, where a wagon stood half-loaded. Festoons of untrimmed grass hung down like curtains all around it. We crawled underneath, between the wheels, into a herb-scented cave of darkness. Rosie scratched about, turned over a sack, and revealed a stone jar of cider.

‘It’s cider,’ she said. ‘You ain’t to drink it though. Not much of it, any rate.’

Huge and squat, the jar lay on the grass like an unexploded bomb. We lifted it up, unscrewed the stopper, and smelt the whiff of fermented apples. I held the jar to my mouth and rolled my eyes sideways, like a beast at a water-hole. ‘Go on,’ said Rosie. I took a deep breath…

Never to be forgotten, that first long secret drink of golden fire, juice of those valleys and of that time, wine of wild orchards, of russet summer, of plump red apples, and Rosie’s burning cheeks. Never to be forgotten, or ever tasted again…

I put down the jar with a gulp and a gasp. Then I turned to look at Rosie. She was yellow and dusty with buttercups and seemed to be purring in the gloom; her hair was rich as a wild bee’s nest and her eyes were full of stings. I did not know what to do about her, nor did I know what not to do. She looked smooth and precious, a thing of unplumbable mysteries, and perilous as quicksand.

‘Rosie…’ I said, on my knees, and shaking.

She crawled with a rustle of grass towards me, quick and superbly assured. Her hand in mine was like a small wet flame which I could neither hold nor throw away. Then Rosie, with a remorseless, reedy strength, pulled me down from my tottering perch, pulled me down, down into her wide green smile and into the deep subaqueous grass.

Then I remember little, and that little, vaguely. Skin drums beat in my head. Rosie was close-up, salty, an invisible touch, too near to be seen or measured. And it seemed that the wagon under which we lay went floating away like a barge, out over the valley where we rocked unseen, swinging on motionless tides.

Then she took off her boots and stuffed them with flowers. She did the same with mine. Her parched voice crackled like flames in my ears. More fires were started. I drank more cider. Rosie told me outrageous fantasies. She liked me, she said, better than Walt, or Ken, Boney Harris, or even the curate. And I admitted to her, in a loud, rough voice, that she was even prettier than Betty Gleed. For a long time we sat with our mouths very close, breathing the same hot air. We kissed, once only, so dry and shy, it was like two leaves colliding in air.

At last the cuckoos stopped singing and slid into the woods. The mowers went home and left us. I heard Jack calling as he went down the lane, calling my name till I heard him no more.

And still we lay in our wagon of grass tugging at each other’s hands, while her husky, perilous whisper drugged me and the cider beat gongs in my head…

Night came at last, and we crawled out from the wagon and stumbled together towards home. Bright dew and glow-worms shone over the grass, and the heat of the day grew softer. I felt like a giant; I swung from the trees and plunged my arms into nettles just to show her. Whatever I did seemed valiant and easy. Rosie carried her boots, and smiled.

There was something about that evening which dilates the memory, even now. The long hills slavered like Chinese dragons, crimson in the setting sun. The shifting lane lassoed my feet and tried to trip me up. And the lake, as we passed it, rose hissing with waves and tried to drown us among its cannibal fish.

Perhaps I fell in – though I don’t remember. But here I lost Rosie for good. I found myself wandering home alone, wet through, and possessed by miracles. I discovered extraordinary tricks of sight. I could make trees move and leapfrog each other, and turn bushes into roaring trains. I could lick up the stars like acid drops and fall flat on my face without pain. I felt magnificent, fateful, and for the first time in my life, invulnerable to the perils of night.

When at last I reached home, still dripping wet, I was bursting with power and pleasure. I sat on the chopping-block and sang ‘Fierce Raged the Tempest’ and several other hymns of that nature. I went on singing till long after supper-time, bawling alone in the dark. Then Harold and Jack came and frog-marched me to bed. I was never the same again…

A year or so later occurred the Brith Wood rape. If it could be said to have occurred. By now I was one of a green-horned gang who went bellowing round the lanes, scuffling, fighting, aimless and dangerous, confused by our strength and boredom. Of course something like this was bound to happen, and it happened on a Sunday.

We planned the rape a week before, up in the builder’s stable. The stable’s thick air of mouldy chaff, dry leather, and rotting straw, its acid floors and unwashed darkness provided the atmosphere we needed. We met there regularly to play cards and scratch and whistle and talk about girls.

There were about half a dozen of us that morning, including Walt Kerry, Bill Shepherd, Sixpence the Tanner, Boney, and Clergy Green. The valley outside, seen through the open door, was crawling with April rain. We sat round on buckets sucking strips of harness. Then suddenly Bill Shepherd came out with it.

‘Here,’ he said. ‘Listen. I got’n idea…’

He dropped his voice into a furry whisper and drew us into a circle.

‘You know that Lizzy Berkeley, don’t ya?’ he said. He was a fat-faced lad, powerful and shifty, with a perpetual caught-in-the-act look. ‘She’d do,’ he said. ‘She’s daft in the ‘ead. She’d be all right, y’know.’

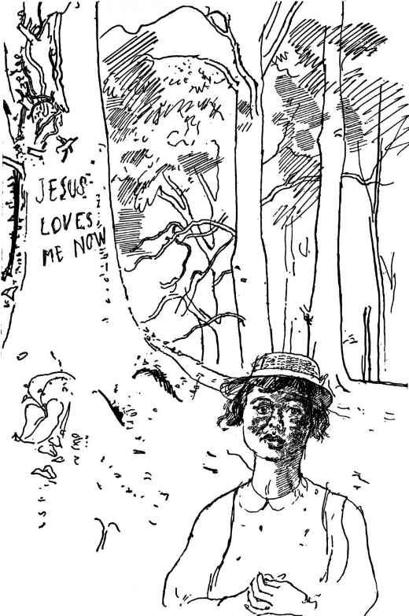

We thought about Lizzy and it was true enough; she was daft about religion. A short, plump girl of about sixteen, with large, blue-bottle eyes, she used to walk in Brith Wood with a handful of crayons writing texts on the trunks of the beech trees. Huge rainbow letters on the smooth green bark, saying ‘Jesus Loves Me Now.’

‘I seen ‘er Sunday,’ said Walt, ‘an’ she was at it then.’

‘She’s always at it,’ said Boney.

‘Jerusalem!’ said Clergy in his pulpit voice.

‘Well, ’ow about it?’ said Bill.

We drew closer together, out of earshot of the horse. Bill rolled us in his round red eyes.

‘It’s like this, see. Blummin’-well simple.’ We listened and held our breath. ‘After church Sunday mornin’ we nips up to the wood. An’ when ‘er comes back from chapel – we got ’er.’

We all breathed out. We saw it clearly. We saw her coming alone through the Sunday wood, chalk-coloured Lizzy, unsuspecting and holy, in the bundle of her clothes and body. We saw her come walking through her text-chalked trees, blindly, straight into our hands.

‘She’d ‘oiler,’ said Boney.

‘She’s too batty,’ said Bill.

‘She’d think I was one of the ‘possles.’

Clergy gave his whinnying, nervous giggle, and Boney rolled on the floor.

‘You all on, then?’ Bill whispered. ‘Wha’s say? ’Ow about it? It’ll half be a stunt, you watch.’

We none of us answered, but we all felt committed; soon as planned, the act seemed done. We had seen it so vividly it could have happened already, and there was no more to be said. For the rest of the week we avoided each other, but we lived with our scruffy plan. We thought of little else but that coming encounter; of mad Lizzy and her stumpy, accessible body which we should all of us somehow know…

On Sunday morning we trooped from the church and signalled to each other with our eyebrows. The morning was damp with a springtime sun. We nodded, winked, and jerked our heads, then made our separate ways to the wood. When we gathered at last at the point of ambush, the bounce had somehow gone out of us. We were tense and silent; nobody spoke. We lay low as arranged, and waited.

We waited a long time. Birds sang, squirrels chattered, the sun shone; but nobody came. We began to cheer up and giggle.

‘She ain’t comin’,’ said someone. ‘She seen Bill first.’

‘She seen ‘im and gone screamin’ ‘ome.’

“Er’s lucky, then. I’d ’ave made ’er ’oller.’

‘I’d ’ave run ’er up a tree.’

We were savage and happy, as though we’d won a battle. But we waited a little while longer.

‘Sod it!’ said Bill. ‘Let’s push off. Come on.’ And we were all of us glad he’d said it.

At that moment we saw her, walking dumpily up the path, solemn in her silly straw hat. Bill and Boney went sickly pale and watched her in utter misery. She approached us slowly, a small fat doll, shafts of sunlight stroking her dress. None of us moved as she drew level with us, we just looked at Bill and Boney. They returned our looks with a kind of abject despair and slowly got to their feet.

What happened was clumsy, quick, and meaningless; silent, like a very old film. The two boys went loping down the bank and barred the plump girl’s way. She came to a halt and they all stared at each other… The key moment of our fantasy; and trivial. After a gawky pause, Bill shuffled towards her and laid a hand on her shoulder. She hit him twice with her bag of crayons, stiffly, with the jerk of a puppet. Then she turned, fell down, got up, looked round, and trotted away through the trees.

Bill and Boney did nothing to stop her, they slumped and just watched her go. And the last we saw of our virgin Lizzy was a small round figure, like a rubber ball, bouncing downhill out of sight.

After that, we just melted away through the wood, separately, in opposite directions. I dawdled home slowly, whistling aimless tunes and throwing stones at stumps and gateposts. What had happened that morning was impossible to say. But we never spoke of it again.

As for our leaders, those red-fanged ravishers of innocence – what happened to them in the end? Boney was raped himself soon afterwards; and married his attacker, a rich farm-widow, who worked him to death in her bed and barnyard. Bill Shepherd met a girl who trapped him neatly by stealing his Post Office Savings Book. Walt went to sea and won prizes for cooking, then married into the fish-frying business. The others married too, raised large families, and became members of the Parish Church Council.