Red Sky at Sunrise: Cider with Rosie, As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, A Moment of War (23 page)

Authors: Laurie Lee

‘It ain’t true! You’re fibbing! Uncle!

‘Just

got

to, boys. See you all in the oven. Scrub yer elbows. Be good. So long.’

Off he’d go at a run: though the Lord knew where,

we

couldn’t think of any place to go to. Then he’d come back much later, perhaps the following night, wet through, with a dog-like grin. He’d be unable to see properly, couldn’t hang up his coat, couldn’t find the latch on the door. He’d sit by the fire and steam and sing and flirt with the squawking girls. ‘You’d best get to bed,’ Mother would say severely: at which he’d burst into theatrical sobs. ‘Annie, I can’t! I can’t move an inch. Got a bone in me leg… Mebbe two.’

One night, after he’d been missing for a couple of days, he came home on a bicycle, and rode it straight down the bank in the stormy darkness and crashed into the lavatory door. The girls ran out and fetched him indoors, howling and streaming with blood. They laid him full length on the kitchen table, then took off his boots and washed him. ‘What a state he’s in,’ they giggled, shocked. ‘It’s whisky or something, Mother.’ He began to sing, ‘O, Dolly dear…’ then started to eat the soap. He sang and blew bubbles, and we crowded around him, never having had any man in our house like this.

Word soon got round that Ray Light was home, laden with Canadian gold. He was set on by toughs, hunted by girls, and warned several times by the police. He took most of this in his powerful stride but the girls had him worried at times. A well-bred young seamstress whom he was cuddling in the picture-palace stole his dollar-crammed purse in the dark. Then one morning Beatie Burroughs arrived on our doorstep and announced that he’d promised to marry her. Under the Stroud Brewery arches, she said: just to clinch it. He had to hide for three days in our attic…

But drunk or sober, Uncle Ray was the same: a great shaggy animal wagging off to his pleasures: a helpless giant, amiable, naive, sentimental, and straightforwardly lustful. He startled my sisters, but even so they adored him: as for us boys, what more could we want? He even taught us how to tie him up, boasting that no knots could hold him. So we tied him one night to a kitchen chair, watched him struggle, and then went to bed. Mother found him next morning on his hands and knees, still tied up and fast asleep.

That visit of Uncle Ray’s, with its games and exhibitions, was like a prolonged Christmas Day in the house. Routine, discipline, and normal behaviour were suspended during that time. We stayed up late, took liberties, and shared his intoxications: while he bounded about, disappeared on his errands, returned in a tousled daze, fumbled the girls, sang songs, fell down, got up, and handed dollars all round. Mother was prim by turns and indulgent with him, either clicking her tongue or giggling. And the girls were as excited and assailed as we, though in a different, whispering way: saying Would you believe it? I never! How awful! or Did you hear what he said to me then?

When he got through his money he went back to Canada, back to the railway camps, leaving behind him several broken heads, fat innkeepers, and well-set-up girls. Soon after, while working in the snow-capped Rockies, he blew himself up with dynamite. He fell ninety feet down the Kicking Horse Pass and into a frozen lake. A Tamworth schoolteacher – now my Aunt Elsie – travelled four thousand miles to repair him. Having plucked him from the ice and thawed him out, she married him and brought him home. And that was the end of the pioneer days of that bounding prairie dog: without whom the Canadian Pacific Railway would never have reached the Pacific, at least, so we believe.

Moody, majestic Uncle Sid was the fourth, but not least, of the brothers. This small powerful man, at first a champion cricketer, had a history blighted by rheumatism. He was a bus-driver too,after he left the Army, put in charge of our first double-deckers. Those solid-tyred, open-topped, passenger chariots were the leviathans of the roads at that time – staggering siege-towers which often ran wild and got their top-decks caught under bridges. Our Uncle Sid, one of the elite of the bus-drivers, became a famous sight in the district. It was a thing of pride and some alarm to watch him go thundering by, perched up high in his reeking cabin, his face sweating beer and effort, while he wrenched and wrestled at the steering wheel to hold the great bus on its course. Each trip through town destroyed roof-tiles and gutters and shook the gas mantles out of the lamps, but he always took pains to avoid women and children and scarcely ever mounted the pavements. Runaway roarer, freighted with human souls, stampeder of policemen and horses – it was Uncle Sid with his mighty hands who mastered its mad career.

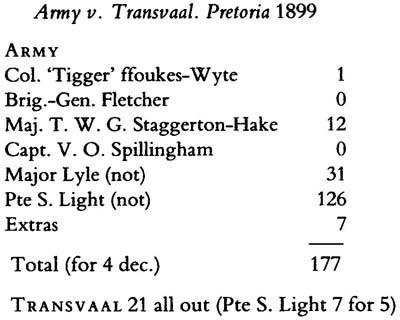

Uncle Sid’s story, like Uncle Charlie’s, began in the South African War. As a private soldier he had earned a reputation for silence, cunning, and strength. His talent for cricket, learned on the molehills of Sheepscombe, also endowed him with special privileges. Quite soon he was chosen to play for the Army and was being fed on the choicest rations. The hell-bent technique of his village game worked havoc among the officers. On a flat pitch at last, with a scorched dry wicket, after the hillocks and cow-dung of home, he was projected straightaway into regions of greatness and broke records and nerves galore. His murderous bowling reduced heroes to panic: they just waved him goodbye and ran: and when he came in to bat men covered their heads and retired piecemeal to the boundaries. I can picture that squat little whizzing man knocking the cricket ball out of the ground, his face congested with brick-red fury, his shoulders bursting out of his braces. I can see him crouch for the next delivery, then spin on his short bowed legs, and clout it again half-way to Johannesburg while he heard far-off Sheepscombe cheer. In an old Transvaal newspaper, hoarded by my Mother, I once found a score-card which went something like this:

This was probably the peak of Uncle Sid’s glory, the time he would most wish to remember. From then on his tale shows a certain fall – though it still flared up on occasions.

There was, for instance, the day of the Outing, when our village took three charabancs to Clevedon, with Uncle Sid driving the leading one, a crate of beer at his feet. ‘Put her in top, Uncle Sid!’ we cried, as we roared through the summer country. Guzzling with one hand, steering with the other, he drove through the flying winds, while we bounced and soared above the tops of the hedges, made airborne by this man at the wheel…

Then on our way home, at the end of the day, we were stopped by a woman’s screams. She stood by the roadside with a child in her arms, cringing from a threatening man. The tableau froze for us all to see; the wild-haired woman, the wailing child, the man with his arm upraised. Our charabancs came to a shuddering halt and we all started shouting at once. We leaned over the sides of our open wagons and berated the man for a scoundrel. Our men from their seats insulted him roundly, suggesting he leave the poor woman alone. But our Uncle Sid just folded his coat, climbed down from his cab without speaking, walked up to the bully, swung back his arm, and knocked the man straight through the hedge. Life to him was black and white and he had reacted to it simply. Scowling with pride, he returned to the wheel and drove us home a hero.

Uncle Sid differed in no way from all his other brothers in chivalry, temper, and drink. He could knock down a man or a glass of beer as readily and as neatly as they. But his job as a bus-driver (and his rheumatism) both increased – and obstructed – his thirst. The result exposed him to official censure, and it was here that the fates laid him low.

When he married my Aunt Alice, and became the father of two children, his job promised to anchor his wildness. But the law was against him and he soon got into scrapes. He was the best double-decker driver in Stroud, without doubt: even safer, more inspired when he drank. Everybody knew this – except the Bus Company. He began to get lectures, admonitions, stem warnings, and finally suspensions without pay.

When this last thing happened, out of respect for Aunt Alice, he always committed suicide. Indeed he committed suicide more than any man I know, but always in the most reasonable manner. If he drowned himself, then the canal was dry: if he jumped down a well, so was that: and when he drank disinfectant there was always an antidote ready, clearly marked, to save everyone trouble. He reasoned, quite rightly, that Aunt Alice’s anger, on hearing of another suspension, would be swallowed up by her larger anxiety on finding him again near to death. And Aunty Alice never failed him in this, and forgave him each time he recovered.

The Bus Company were almost equally forgiving: they took him back again and again. Then one night, having brought his bus safely home, they found him fast asleep at the wheel, reeking of malt and stone-jar cider: and they gave him the sack for good.

We were sitting in the kitchen rather late that night, when a loud knock came at the’ door. A hollow voice called ‘Annie! Annie!’ and we knew that something had happened. Then the kitchen door crept slowly open and revealed three dark-clad figures. It was Aunty Alice and her two small daughters, each dressed in their Sunday best. They stood at the foot of the kitchen steps, silent as apparitions, and Auntie Alice’s face, with its huge drawn eyes, wore a mantle of tragic doom.

‘He’s done it this time,’ she intoned at last. ‘That’s what. I know he has.’

Her voice had a churchlike incantation which dropped crystals of ice down my back. She held the small pretty girls in a majestic embrace while they squirmed and sniffed and giggled.

‘He never came home. They must have given him the sack. Now he’s gone off to end it all.’

‘No, no,’ cried our Mother. ‘Come and sit down, my dear.’ And she drew her towards the fire.

Aunty Alice sat stiffly, like a Gothic image, still clutching her wriggling children.

‘Where else could I go, Annie? He’s gone down to Deadcombe. He always told me he would…’

She suddenly turned and seized Mother’s hands, her dark eyes rolling madly.

‘Annie! Annie! He’ll do himself in. Your boys – they just

got

to find him!…’

So Jack and I put on caps and coats and went out into the half-moon night. From so much emotion I felt light-headed: I wanted to laugh or hide. But Jack was his cool, intrepid self, tight-lipped as a gunboat commander. We were men in a crisis, on secret mission, life and death seemed to hang on our hands. So we stuck close together and trudged up the valley, heading for Deadcombe Wood.

The wood was a waste of rotting silence, transformed by its mask of midnight: a fine rain was falling, wet ferns soaked our legs, leaves shuddered with owls and water. What were we supposed to do? we wondered. Why had we come, anyway? We beat up and down through the dripping trees, calling ‘Uncle!’ in chill, flat voices. What should we find? Perhaps nothing at all. Or worse, what we had come to seek… But we remembered the women, waiting fearfully at home. Our duty, though dismal, was clear.

So we stumbled and splashed through invisible brooks, followed paths, skirted ominous shadows. We poked bits of stick into piles of old leaves, prodded foxholes, searched the length of the wood. There was nothing there but the fungoid darkness, nothing at all but our fear.

We were about to go home, and gladly enough, when suddenly we saw him. He was standing tiptoe under a great dead oak with his braces around his neck. The elastic noose, looped to the branch above him, made him bob up and down like a puppet. We approached the contorted figure with dread; we saw his baleful eye fixed on us.

Our Uncle Sid was in a terrible temper.

‘You’ve been a bloody long time!’ he said.

Uncle Sid never drove any buses again but took a job as a gardener in Sheepscombe. All the uncles now, from their wilder beginnings, had resettled their roots near home – all, that is, save Insurance Fred, whom we lost through prosperity and distance. These men reflected many of Mother’s qualities, were foolish, fantastical, moody; but in spite of their follies they remained for me the true heroes of my early life. I think of them still in the image they gave me; they were bards and oracles each; like a ring of squat megaliths on some local hill, bruised by weather and scarred with old glories. They were the horsemen and brawlers of another age, and their lives spoke its long farewell. Spoke, too, of campaigns on desert marches, of Kruger’s cannon, and Flanders mud; of a world that still moved at the same pace as Caesar’s, and of that Empire greater than his – through which they had fought, sharp-eyed and anonymous, and seen the first outposts crumble…