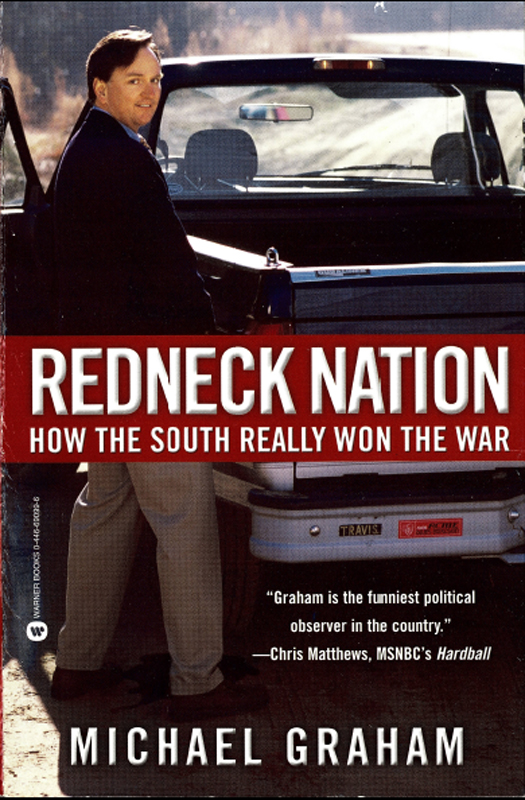

Redneck Nation

Authors: Michael Graham

REDNECK NATION

“Yes, Northerners and Southerners talk differently, and, yes, we eat differently and vote differently and express our arguments

differently, but the same Old South principles are at work. Somehow—and I’ll be damned if I can figure it out—the South lost

the Civil War of 1860, lost the civil rights struggle of 1960, but has managed to win the battle of ideas.

“This is not a good thing. The South is a land of few ideas, nearly all of them bad. And if you’re a typical modern Northern

American, they are probably yours.”

“Michael Graham may make you laugh or he may really annoy you, but one thing is for certain: He’s the funniest person ever

to come out of Pelion, SC.”

—Charlotte Observer

“Hilarious…. [Graham] examines the peculiar phenomenon with a cynical wit that spares no one, including himself.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Graham takes a hilarious, albeit painfully honest, look at what he believes is America’s cultural collapse.”

—Richmond Times-Dispatch

“Michael Graham has written an adroit and devastating cultural analysis with at least one laugh on every page, but what really

makes REDNECK NATION memorable are the number of times I stopped in mid-laugh to find myself thinking, ‘Oh, God help us, it’s

true.’”

—Florence King

“With fluid style and piercing intelligence, Michael Graham ably demonstrates the ‘Redneck’ nature of modern Liberalism….

Jam-packed with prescient analysis and biting satire.”

—Conservative Monitor

“Redneck is only another term for WASP, and this book infused me with a deep and disturbing sense of Anglo-Saxon identity

politics.”

—Christopher Hitchens

“Smart-mouthed and lighthearted… a laugh-out-loud funny rant.”

—NationalReview.com

“Funny and insightful. You’ll really enjoy [this book].”

—G. Gordon Liddy

“Michael Graham proves you can be Southern, funny, and smart!”

—Jeff Foxworthy, comedian

Copyright © 2002 by Michael Graham

All rights reserved.

Warner Books

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

Originally published in hardcover by Warner Books, Inc.

First eBook Edition: November 2009

ISBN: 978-0-446-56959-0

To my father, Simon Graham of Horry County, SC, who taught me never to trust a Yankee; and to my mother, Patricia Futrell

Graham of Los Angeles, CA, who told me that nothing good ever came out of the South.

You were both right.

Contents

You are living in a REDNECK NATION

2. How the South Really Won the War

6. Nothing Gets This Bad Except on Purpose: Redneck Education

10. It’s a ___ Thing. You Wouldn’t Understand.

Epilogue: Confessions of a Reluctant Southerner

My first college roommate at Oral Roberts University was John, a thirty-seven-year-old captain in the Nigerian Army. We were

thrown together in one of those inexplicable twists of fate that are, for me, indisputable truth that there is a God and He

writes for Monty Python.

I was an eighteen-year-old white kid straight from the rural South. A graduate of the South Carolina public school system,

I came to Oral Roberts because of a deep, spiritual calling to attend whatever university was farthest from South Carolina

and offered me a full scholarship. That’s how I ended up in the shadow of the Prayer Tower in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

John spoke seven languages, none of them English. At least, not that I could tell. And though he was an officer in a national

army that regularly fired on its own citizens without apology, John himself was a gentle, almost gregarious man. That fact

did not lessen the shock a southern white boy feels on his first morning away from home when he is awakened at dawn by a large

black man in Nigerian cammies doing anticommunist calisthenics at the foot of his bed.

John had never been to America before. His knowledge of our country came almost entirely from his exposure

to commercial television back in Africa. And so our first conversation went something like this:

JOHN: Where were you born, Michael?

ME: Los Angeles, California.

JOHN: California! Hollywood, movie stars!

ME: How do you like it here in Oklahoma?

JOHN: Oklahoma! Cowboys, Indians, Wild West! So where do you live now?

ME: Actually, I grew up down in South Carolina…

JOHN: South Carolina! The American South! Dixie! Ah, the South, ahem… Oh. I see.

Later that night, I found him checking my pillowcases for eyeholes.

Here’s a guy from Africa who doesn’t know Montana from Maryland and thinks Walt Disney was one of our greatest presidents,

but he knows enough about the South to assume that every white guy from South Carolina is in the KKK.

I didn’t think much of this southern stereotyping at the time because I was used to it. In fact, not only was I unfazed by

charges that white southerners were racist, redneck hicks, I was an enthusiastic witness for the prosecution.

There is no other way to put it: I hated growing up in the South. From the age of six, I lived in the rural town of Pelion,

South Carolina, a picturesque community of 211 hearty southern folk, where I spent my formative years running from large,

hairy people named “Bubba,” many of them women.

The public school was a single campus that accommodated

all twelve grades, so I spent my entire educational career with the same group of drawling, intellectually uninspired mouth-breathers,

most of whom thought I was a pinhead who read too many books.

The students didn’t like me, either.

I spent my summers cropping tobacco in the Pee Dee region of South Carolina, home of NASCAR’s Darlington International Speedway

and one of America’s highest rates of sexually transmitted diseases, which, due to local cultural traditions, would often

spike immediately after large family reunions.

It was during one of these summers working tobacco that I learned how powerful racism was as a social force in the South:

A black coworker pulled a knife on me late one afternoon in one of the sweltering tobacco barns. Back then the barns were

tall, narrow, heat-holding structures with huge rails—skinned tree trucks, actually—used for hanging sticks of green tobacco

while they cured. My black assailant was only half serious and we were both very young and who knows if we were on the verge

of a fight or a tutorial on fingernail cleaning, but when the knife appeared, the same redneck barn workers who had tortured

me throughout the summer began dropping from the railings above to rescue me. They seemed to appear out of thin air, like

Army Rangers dropping from Black Hawks in a firefight.

After beating the crap out of the black field worker and his friends, one of the older boys in the group looked at me and,

seeing the wonder across my face, said, “Don’t worry—we still hate you, too.”

To this day, I think he meant it in a nice way.

Back home, my family and I attended a series of small

evangelical churches, the kind where the casting-out of demons was a regularly scheduled part of services. These were old-time,

red-meat “Thank you, Jesus!” southern churches with a Pentecostal flair. I never attended a church with a mainstream name:

no First Baptist or Elm Street Methodist. No, we always seemed to be the newest members of places called Springdale Revival

Center or Shekinah Temple or God’s Gonna Smite Yo’ Ass-embly of God.

And so I grew up going to church four or five times a week and playing “fuhtbawl” and hunting squirrels and getting called

“nigger lover” and having the Great American Southern White Boy Experience. All that was missing was a banjo and severe dental

problems.

Which is why I never complained when Northerners (or Nigerians) cracked wise about me or my homeland. When I saw movies or

TV shows mocking the South as an inbred backwater of racial obsession, good-ol’-boy politics, and

Hee Haw

culture, I didn’t grouse because I knew they were right. All I had to do was look around my living room.

But I also inferred that these Northerners who were looking down on us were doing so because they were different. I just assumed

they mocked southern ideas and attitudes because they, as Northerners, found them at the least strange, at the most repulsive,

and, under any circumstances, unacceptable.

So it threw me off my stride when, less than fifteen minutes after arriving in Boston, Massachusetts, for the first time,

the very first white person I spoke to used the word “nigger.”

I had just pulled into town and needed directions. I

stopped at a gas station where a burly, blue-shirted white guy with his name over the pocket barked at me (or is that “baaked”

at me), “You’re all turned around, buddy. This is Nigger Town.”

My head almost snapped back. Here I was, eight hundred miles north of the redneck wonderland I had fled in rural South Carolina,

and the first Yankee I talk to is a racist idiot. I couldn’t believe it. Then I saw him glance at my out-of-state license

plate. “Aha,” I thought to myself, “he’s just going native on me as a southerner. It’s really my fault,” I told myself in

a pathetically codependent way.

And in a way, it

was

my fault. I spent six years doing stand-up comedy, traveling to forty-one states and performing for thousands of people;

I spent six more years working as a GOP political consultant in places like Chicago and Westchester County, New York, talking

to volunteers and voters from both sides of the political aisle. And inevitably I found that not only did northerners assume

I was a closet Klan member but they had my tacit permission to slip on the intellectual white sheet as well.

In 1997, I was at a cocktail party in Westchester County, which is ground zero for limousine liberalism in America, the kind

of place where Bill Clinton’s annoying mix of self-absorption and self-righteousness would fit right in. Surrounded by Manhattan

expatriates, SUV socialites, and liberals with causes, I happened to mention that I’m from South Carolina. It turns out one

of the gathered had gone through army basic training at Fort Jackson in Columbia. Without so much as a sidelong glance, he

tells me:

“I like you southerners. You sure know how to handle your niggers.”

I have since discovered that incidents like these are

hardly the exception. Yes, I realize that anecdotes alone aren’t sufficient for drawing grand conclusions about society north

of the Mason-Dixon line. But after a lifetime fleeing my southern heritage and looking for that place in America that practices

(for the lack of a better term) “Northernism,” I am persuaded that no such place exists. As Gertrude Stein said of Oakland,

there is no there there.

I’ve eaten Maxwell Street hot dogs near Chicago’s Cabrini Green, Norwegian

lefse

in Minnesota, sturgeon from the Columbia River, lobster rolls in Massachusetts, ribs in Kansas City, homemade salsa in Los

Angeles, and mounds of fries and gravy at the diner around the corner from the Improv in New York.

I’ve driven through the Rockies a half dozen times, gotten into arguments with snot-nosed college pukes on the steps of a

Boston comedy club, suffered through a program of awful Italian folk songs sung in worse Italian by Sicilian wanna-bes in

Yonkers, New York, and had a shotgun pulled on me at a gas station in Umatilla, Washington.