Reluctant Genius (15 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

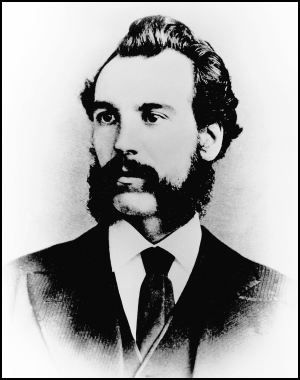

At twenty-seven, Alec Bell was intense, shy, and overwhelmed by passion.

By now, there were sounds of giggles and chatter outside the parlor’s closed oak door. Gertrude’s four daughters were eager to walk over to Harvard Yard and watch the sons of America’s elite take their degrees. There would be so much to see on the university’s leafy grounds! Some of the most distinguished professors on the continent, including Charles Eliot Norton and William James, would circulate through the crowd. Local celebrities like poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and author Henry James might make appearances. The cream of New York society would be there, twirling their parasols as their offspring swaggered through the quadrangles for the last time. The parade of Fifth Avenue fashions, provided gratis by Social Register families, would provide conversational fodder for weeks.

As Alec walked down Brattle Street with the Hubbard ladies, he managed to subdue his nerves sufficiently to start a conversation with Mabel. In Harvard Yard the afternoon sun cast a rosy glow on the old red brick of the dormitories, and the two young people chatted between the various graduation orations. Alec was captivated, as usual, by Mabel’s sweet smile and serious manner. But this was the first time he had conversed with her as a suitor rather than a teacher. His feelings overflowed: he was almost incoherent with self-consciousness. As she kept her eyes trained on his lips, paying earnest attention to what he was saying, she seemed to him so much more mature and intellectual than her lively younger sisters. He felt, he told his parents, that “she evidently took some pleasure in my society.” He could see “that she had not been informed of what had passed between her mother and myself [and] was perfectly unconscious of what was passing in my mind.”

Mabel’s father, Gardiner Greene Hubbard, was horrified by Alec’s impulsiveness.

Gardiner Hubbard had been in New York when Alec had declared his feelings about Mabel to Gertrude. When Mabel’s father came home two days later and heard what was going on, he was much less sympathetic toward his protégé than his wife had been. Alec noted tersely, in a diary, that Hubbard “thought Mabel much too young. Did not want thoughts of love and marriage put into her head. If Mrs. Hubbard had not said

one

year, he would have said two…. Did not think I was ready to be engaged. No objections personally.”

The Hubbards were far from hostile to Alec. Gardiner Hubbard knew he could not afford to alienate his daughter’s suitor. Alec represented his best hope of beating Orton to a viable multiple telegraph, and thus to repairing his own fortunes. Mabel’s father was torn between his view of his daughter’s best interests and his support for Alec’s scientific endeavors. “He said he had felt quite an affection for me from the very first time he saw me,” Alec told his parents. “That this had led him to offer his assistance in regard to the ‘Telegraph’—that he believed I had great talents—and that his object in aiding me in the Telegraphic Scheme was not alone a speculation on his part, but in the hope of encouraging me to devote myself to science.”

According to Alec’s diary for this anguished period, Mabel’s deafness was never mentioned in the many intense conversations between Alec and her parents. Instead, like his wife, Hubbard wondered about Alec’s emotional stability. And despite his ostentatious belief in the principle of meritocracy, he knew that the Bell family was, by Boston standards, rather shabby. How could this impoverished young man, who had no family money or status, support Mabel? A little caution was the least that Gardiner Hubbard asked.

Mr. Hubbard’s haughty remarks dampening Alec’s hopes were delivered in the Brattle Street parlor. To soften the blow, Hubbard suggested Alec join the ladies in the garden. Alec stepped out of the French windows into the warm evening air and saw Mrs. Hubbard’s canna lilies glowing in the dusk. There he found Mabel and suggested they take a quiet stroll down one of the gravel walks. He meant to keep silent, as the twilight was too dim for Mabel to see his lips clearly, but with Mabel’s hand resting on his arm he could not prevent a few awkward words escaping.

Then Mabel’s sister Roberta and cousin Mary Blatchford appeared. Under Cousin Mary’s caustic gaze, mischievous Roberta began to play “he loves me, he loves me not” with some of Mrs. Hubbard’s asters. The flower she selected for Alec came out, to her delight, as “Love.” In his private diary, Alec recorded how Mabel innocently asked him of whom he was thinking. Alec stared helplessly at her, unable to speak. Berta and Mary burst out laughing and said

they

knew who was in their guest’s thoughts. Alec was left suffused with embarrassment, and wondering who would spring to Mabel’s mind in similar circumstances. They all retreated to the brightly lit veranda, and he heard himself blurt out, “If you could choose a husband, what would you wish him to be like?” Mabel turned her large gray eyes on him in confusion: her teacher’s inquiry seemed indelicate and impertinent. She feared he was mocking her. Alec winced at his own faux pas. In his diary he wrote, “Betrayed my feelings—fear Mabel may be laughed at on account of my foolish proceedings.”

But at least he had spoken out. He no longer felt like an emotional pressure cooker about to burst.

On July 1, Mabel left as planned with her McCurdy cousins, to spend the summer under the watchful eye of Mary Blatchford on Nantucket. With its clapboard architecture, rambling roses, and history as a whaling center, Nantucket was a favorite vacation spot for wealthy Bostonians. Cousin Mary, now in her late twenties, was a woman in the mold of Olive Chancellor, the character described by Henry James in

The Bostonians

as “a spinster as Shelley was a lyric poet, or as the month of August is sultry. There are women who are unmarried by accident, and others who are unmarried by option; but Olive Chancellor was unmarried by every implication of her being.” Mary Blatchford could be relied upon to see that the young people behaved themselves. Like Olive Chancellor, she “knew her place in the Boston hierarchy” and had carefully honed instincts about who would—or wouldn’t—“do.” No disreputable beaux would cross her threshold.

Alec planned to remain in Boston to pursue his telegraph experiments. It was an awful month. He remained isolated and fretful because he felt too unsettled to pay a call on the Hubbard household in Cambridge. His assistant, Watson, was sick. He continued alone with his telegraph experiments, but he could not concentrate and he was too clumsy to make the minute adjustments at which Watson excelled. He felt himself becoming almost unhinged by the tension and apprehension. Only the elderly Mrs. Sanders was at hand in Salem to comfort the distracted young Lothario. Her lodger’s growing agitation convinced her that he was suffering from “brain fever brought on by telegraphy.”

In late July, Alec could bear the tension no longer. He summoned his courage to return to Cambridge. As he noted in his diary, “Called on Mr. and Mrs. Hubbard. Told them that I could not help myself. Should tell Mabel what was in my mind if they gave me the opportunity. Thought she

should

know it. I could only avoid telling her by avoiding

her

.”

The Hubbards were horrified as Alec, quivering with emotion, blurted out his feelings. They had hoped he would calm down, dutifully devote himself to science, as Gardiner had suggested, and suppress his feelings for Mabel for at least another year. Now here he was, striding about in their parlor, running his long fingers through his lank black hair, even more frenzied than he had been four weeks earlier. The intensity of his passion shook them, especially when Alec announced he would go to Nantucket to speak to Mabel himself. Such a step, they insisted, would startle and distress their daughter. Alec must take control of himself and wait until Mabel returned to Cambridge in early August. Once she was reunited with her mother, Alec might speak to her. A chastened Alec dutifully returned to Salem and tried to abide by the Hubbards’ advice.

In Nantucket, Mabel had now been under the wing of bossy and overprotective Mary Blatchford for four weeks. Cousin Mary had divined the awkward Scotsman’s feelings, and she disapproved. She didn’t like Alec’s shiny black suit and lack of pedigree. She also realized that Mabel was unaware of his inclinations. So as she and Mabel, clad in baggy knee-length bathing dresses and rubber bonnets, plunged into the icy Atlantic, she decided to meddle. She casually asked Mabel how she felt about Alec. She encouraged her impressionable cousin to denigrate her teacher. She reported to Mabel’s parents, “I… more or less told her she did not care for him, nor did she seem to care.” In particular, Mary made fun of Alec’s conduct in the garden. Like any vulnerable young woman, Mabel felt that Mary was ridiculing her as well as Alec, and she instinctively shrank from the incident. Coached by Mary, she confided to her mother in her next letter home that she really

disliked

her former tutor, particularly his long greasy dark hair and black eyes. Blue eyes, she insisted, were more to her taste.

In an effort to dampen Alec’s hopes, Mrs. Hubbard summoned him to Cambridge and read him passages from Mabel’s letter. Although Gertrude meant well, it was a cruel thing to do, and it sent Alec into a fury of despair. “Don’t know what is best to do—quite distressed about it—as such dislikes have a tendency to be permanent,” he noted in his diary. His head ached, and he tossed and turned through the sultry August nights. As he guilelessly explained to Gertrude Hubbard in yet another emotional letter, “I do not know how or why it is that Mabel has so won my heart. It is as great a mystery to me as it must be to you…. I should probably have sought one more mature than she is—one who could share with me those scientific pursuits that have always been my delight. However, my

heart

has chosen.” He desperately wanted to explain his feelings to Mabel himself, to tell her “all that is in my heart, and let her deal with me as she chooses.”

But then Alec had to undergo a further turn of the screw. Another letter from Mabel arrived at the Hubbards’ home, and Mrs. Hubbard felt obliged to summon him back to Brattle Street again so she could read yet more extracts to him. Mabel herself was now in a spin. Manipulative Mary had continued her campaign: she had told Mabel that Alexander Graham Bell wanted to marry her and had already spoken to her parents. Mabel was shocked, and her letter reflects her own youth, her confused feelings, and her dependence on her mother for advice. Yet there is also an undercurrent of independence in her response, and a belief in her right to be informed about matters concerning her. Her letter reveals a much more stable temperament than Alec’s.

My darling Mamma,

…I think I am old enough now to have a right to know if he spoke about [marriage] to you or Papa. I know I am not much of a woman yet, but I feel very very much what this is to have as it were, my whole future life in my hands…. Oh Mamma, it comes to me more and more that I am a woman such as I did not know before I was. I felt and feel so much of a child still so very young I had no idea of marrying or being sought in marriage yet a while…I…feel more and more how unfitted and unworthy I am of such a position as a woman and wife. Of course it cannot be, however clever and smart Mr. Bell may be, and however much honored I should be by being his wife I never never could love him or even like him thoroughly. But this does not lessen the feeling of responsibility it gives me—even awe. Oh, it is such a grand thing to be a woman, a thinking, feeling, and acting woman, to be thought fit to be the life’s companion and mother of the children of a man. But is it strange I don’t feel at all as if he did it through love….

I wish I had you here that you might speak to me sensibly and clearly and tell me all how I ought to feel.… You need not write about me accepting or declining this offer if it should be made. I feel almost as if I’d die first.… I must hear from you to clear me up, I feel so misty and befogged I don’t want to think or feel things I ought not.…Help me please,

Your own, Mabel.