Reluctant Genius (18 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

This meant that Alec could not file a patent application in Washington until Brown had been granted the British patent. But, unknown to Alec, Brown had lost interest in the invention after being told by a London lawyer that it was worthless. While Alec eagerly awaited news of his British patent, the application lay forgotten at the bottom of Brown’s suitcase as he dined with old friends at the Travellers Club on Pall Mall. Back in Boston, Gardiner Hubbard struggled to control his irritation.

This time, however, Hubbard realized it was smarter to avoid another showdown with his excitable protégé. In February 1876, without consulting Alec, he went ahead and filed on Alec’s behalf for a patent on the “speaking telegraph.” He dropped off at the U.S. Patent Office in Washington the application with its descriptions of Alec’s electrical theories and of the crude apparatus that Alec and Watson had built.

At first, Alec was furious with Hubbard for taking matters into his own hands. But Hubbard’s action was crucial. Two hours after Hubbard’s call on the U.S. Patent Office, Elisha Gray filed a caveat there. The caveat, or warning, served notice to other inventors that Gray was working on the transmission of speech by electricity. Since Gray, unlike Alec, had not yet succeeded in transforming his theories into practice by constructing the apparatus that would demonstrate his theories, he could not apply for a full patent. On March 3, Alec’s twenty-ninth birthday, the United States Patent Office announced that it had granted Patent No. 174,465 to Alexander Graham Bell for a “speaking telegraph.” His patent gave his invention seventeen years of protection in the market. If anybody else was working on a “speaking telegraph,” they now had to prove that their idea was completely different from Alec’s. Alec Bell had won the first stage of the race. He acknowledged that Hubbard had done the right thing, and he proudly presented the patent certificate to Mabel, who hung it in her second-floor study in Brattle Street.

But there was no time to lose in self-congratulation. Both Alec and Tom Watson knew that their invention was far from fully developed: it had yet to transmit a clear message. They moved their workshop to the privacy of Alec’s new Boston lodgings at 5 Exeter Place, and spent hours fiddling with the equipment in order to make the vocal transmission distinctly audible. Alec thought a different kind of battery, which would strengthen the electric current carrying the sound, would improve clarity. “I had made for Bell a new transmitter,” described Watson later, “in which a wire, attached to a diaphragm, touched acidulated water contained in a metal cup, both included in a circuit through the battery and the receiving telephone. The depth of the wire in the acid and consequently the resistance of the circuit was varied as the voice made the diaphragm vibrate, which made the galvanic current undulate in speech form.” On the evening of March 10,1876, Alec and Watson set up the receiver on the bureau in Alec’s bedroom, then took the transmitter with its battery connected to the cup of sulfuric acid into the room next door. Watson barely had time to return to the bedroom before he heard Alec’s voice emanating from the receiver, saying, quite clearly, “Mr. Watson, come here, I want you!"

In Alec’s account of this historic moment, Watson rushed out of the bedroom declaring he had heard clearly the message. Tom Watson’s account is far livelier. He recalled not only the message, but also a note of urgency in his boss’s voice: “I rushed down the hall into his room and found he had upset the acid of a battery over his clothes. He forgot the accident in his joy over the success of the new transmitter when I told him how plainly I had heard his words… . His shout for help on that night … doesn’t make as pretty a story as did the first sentence, ‘What hath God wrought!’ which Morse sent over his new telegraph … thirty years before, but it was an emergency call—therefore typical of the great service the telephone was to render to mankind."

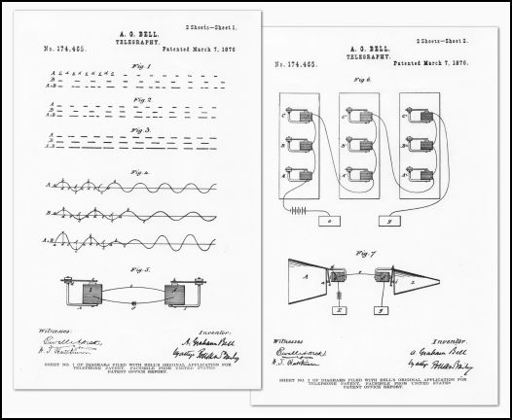

The crucial telephone patent illustrated Alec’s undulating current theory (Figs. 1-4), reed receivers (Fig.

5,),

and circuitry for the harmonic telegraph (Fig. 6) and his telephone (Fig. 7).

Whatever the truth of the matter, there is no doubt that inventor and technician exploded with excitement at the breakthrough they had wrought. Then they changed places, so Alec could hear Tom read from a book into the mouthpiece. The two young men spent the rest of the night laughing and testing the transmitter over and over again, until Alec ended the world’s first telephone conversation with the words “God save the Queen!” The solemnity of this sign-off lasted only a moment. Loyalty to Queen Victoria was supplanted by the exuberance of the Mohawk war dance that George Johnson had taught him several summers earlier in Brantford. Now, as the sun rose beyond the dusty windows of Exeter Place, Alec gleefully entertained Tom Watson with war whoops and stamping.

Alec’s notes on the first successful transmission of speech.

Success was sweet. Alec told his father, “This is a great day with me.” Alec might have exasperated his patrons with his scatter-brained enthusiasms, but the reach of this young, self-educated man s vision is illustrated in his next remark: “The day is coming when telegraph wires will be laid on to houses just like water or gas—and friends converse with each other without leaving home.” Today we take such communication totally for granted. In 1876, when three-quarters of the population of North America spent their entire lives in the isolated rural communities in which they were born, when electric lighting was still a decade away, and when a reliable mail service was regarded as a miracle, most people dismissed such a notion as fantasy.

Alec’s fiancée quickly recognized the world-shaking significance both of the technical breakthrough and of the patent. Alec, Gardiner Hubbard, and Thomas Sanders now had a monopoly on an extraordinary new technology—as long as they moved quickly into production and the patent wasn’t contested. Mabel wrote to Alec, “How can I tell you how very glad I am for you, I am so glad you have at last obtained this patent for which you worked so hard and have now as you say a fair prospect of success. I am just as happy as can be.” She herself had worked hard to understand the science behind Alec’s instruments. ("I want to know all about yourself and your ideas,” she instructed him, although, tongue in cheek, she added, “so far as you consider possible for a poor ignorant, feeble-minded

woman

to understand.") Her father’s faith in her fiancé had paid off, and the brilliance she knew he possessed had been recognized in Washington. “You don’t know how much my heart is in your work or how anxious I am that you should succeed,” she wrote from Cambridge a few months later. “I want so much that you should take your place among scientific men."

But Alec continued to be torn three ways—between demands from his own father to keep working on Visible Speech, pressure from Mabel’s father to concentrate on telegraphy, and his own commitment to the deaf. Despite the excitement of the breakthrough, he clung to his self-selected mission. “You must settle down to the conviction,” he replied to Mabel, “that whatever success I may meet with in life— pecuniary or otherwise—your husband will be known as a teacher of the deaf…. I see so much to be done—and so few to do it."

Mabel was more hard-headed than Alec. Her own deafness did not convince her that Alec should devote his life to her fellow sufferers— indeed, she never thought of herself as a sufferer, and she rarely mingled with other deaf people. In later life, she would admit that “when I was young and struggling for a foot-hold in the society of my natural equals, I

could not

be nice to other deaf people. It was a case of self-preservation.” Right now, she shared her father’s fear that Alec would let slip his immediate opportunity to make his fortune with the telephone because of this yearning to help the afflicted. Although she herself had a good working knowledge of Visible Speech, she didn’t really see much future in it and thought it a waste of Alec’s talents—although she never dared admit this to Alec. Visible Speech “will be of greatest value to learners, deaf or hearing, but I think it will be a long time before it will come into general use,” she gently informed him. “There may be money in it but you are not the one to get that money because you love your work and cannot bear to ask pay for that labor of love.” Success with the telephone, she pointed out, would give him the financial freedom to devote himself to the interests of the deaf, “[s]o for that reason I think it would be better if you made Visible Speech secondary to the telephone.” In letters and speech, Mabel had a certain tone of voice to which, over the years, Alec would learn to listen carefully.

The Hubbard household in Cambridge was now Alec’s second home. Several evenings a week, he would lope along Brattle Street to be welcomed at the door of Number 146 by a radiant Mabel. After dinner, Gertrude Hubbard would ask him to play the piano, or Mabel’s sisters would beg him to tell them about Scotland. Alec, once so somber and awkward in this wealthy, youthful company, now reverted to the boy who had entertained his own cousins in Edinburgh. Surrounded by Gertrude, Grace, and Berta Hubbard and by Augusta, and Caroline (Lina) McCurdy, clad in shimmery silks and taffetas or well-starched lace and linens, Alec recited the poetry of Robbie Burns or recounted the plots of Walter Scott’s novels. Augusta remembered how “[w]e would all gather round the piano while he played and sang, or ... he would hold us spellbound, with his wonderful tales of old Scotland, for he was then as always a most charming story-teller.” After the loss of his own brothers and his years of intense and lonely labors over his lab bench, Alec enjoyed being, in Augusta’s words, “one young man among a lot of pretty young girls.” And Mabel, perched close to her fiancé and watching his lips carefully, reveled in Alec’s popularity with her family.

That spring, Alec had to submit to the prenuptial obligation of meeting Mabel’s relatives, as was expected of every well-bred young couple in the 1870s. Knowing Alec’s eagerness to focus on his invention, Mabel kept visits to the minimum. However, she worried about the impression that Alec, who rarely paid much attention to his appearance and often forgot to get his hair cut, might make. “Be sure you keep looking very nice and clean, and do me credit my dear,” she advised her future husband. Her cousins were all amazed that Mabel, aged only eighteen and unable to hear, should be the first of their number to become betrothed. And they were intrigued that she was marrying outside their circle. “International marriages were not as common then as now,” recalled Augusta McCurdy half a century later, ’and even Canada seemed far away"

In New York, Mabel’s McCurdy grandparents were most impressed with her clever young Scotsman. Robert McCurdy, a self-made man who had built up his own dry goods business, didn’t share Gardiner Hubbard’s Brahmin distaste for uncombed hair, shiny suits, and poverty. The McCurdys were also more realistic than Mabel’s doting parents about her marital opportunities. They knew that there would be prejudice against Mabel’s deafness and strange speech within Boston’s upper crust. Robert McCurdy thought that Mabel had done well to find a man so sympathetic to the challenges of hearing loss.

Alec had refused to continue as Mabel’s speech instructor once they were engaged. Clasping her hand and looking deep into her wide gray eyes, he explained that he wanted to be her lover, not her teacher. But despite the improvements he had already made to her speech, even her family sometimes found the contorted vowel sounds of her speech hard to understand. “Mamma says I try so manfully to read your letters [aloud] aright that no one can understand a word I say,” she told Alec on one occasion. Strangers often assumed that this well-dressed young woman was stupid when she just stared at them; they rarely realized she was struggling to read their lips (a task made more difficult by the thick beards then in fashion for men). With Alec, however, she was totally uninhibited. When she accompanied Alec on a walk, no one remarked on the lively chatter between the tall, thin professorial-looking figure and his high-spirited, long-haired companion, whose eyes were fixed so lovingly on his face. Passersby smiled indulgently at the obvious mutual affection, not realizi

ng that Alec

and Mabel were always holding hands or linking arms because touch was such an important form of communication for them. The only unusual aspect of their conversations emerged on dark nights. On evening strolls, Mabel would do all the talking between street lamps, and then the two would pause under the popping gaslight while Alec replied. If the couple took an evening drive, they often carried a candle in the carriage so they could converse without interruption.