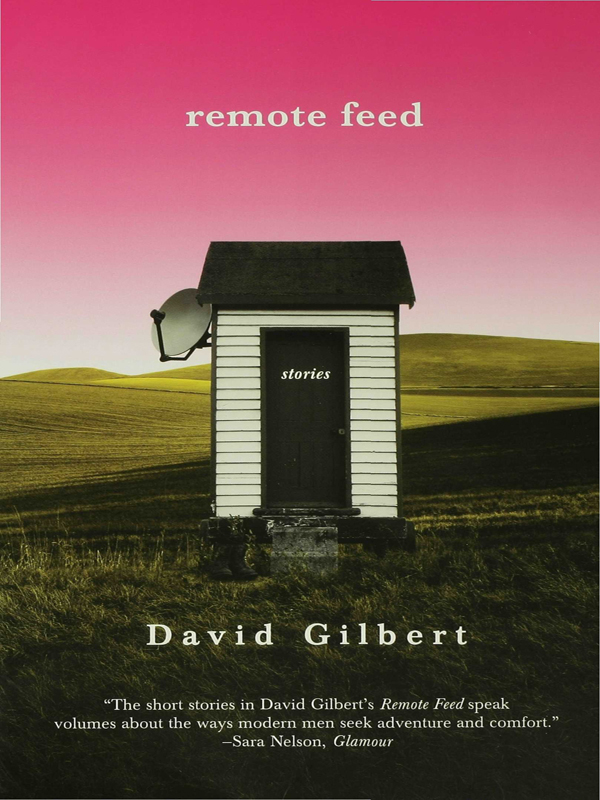

Remote Feed

Authors: David Gilbert

Praise for

Remote Feed

'The short stories in David Gilbert's

Remote Feed

speak volumes about the ways modern men seek adventure and comfort."

—Sara Nelson,

Glamour

"One is mesmerized by Gilbert's daring and absolute persuasiveness. . . . [A] distinctive voice."

—

Time Out

"Scathing writing can be exhilarating."

—Michelle Goldberg,

Salon

"The action in Gilbert's fast, witty, unnerving stories is dark and edgy to be sure, but his prose gleams, a beacon in the

fog of our numb days and nights."

—Donna Seaman,

Booklist

"If you read one short-story collection all year, promise me it will be Gilbert's. . . . He's just about the funniest social

commentator since Fran Lebowitz. . . . To call Gilbert insightful is an understatement."

—Gina Vivinetto,

St. Petersburg Times

(Florida)

"An intelligent Darwinian debut collection . . . [the] writing [has] zest."

—

Kirkus Reviews

"Recommended for literary collections."

—Christine DeZelar-Tiedman,

Library Journal

"David Gilbert is one of those rare new writers who bursts in the sky like a new star. I read

Remote Feed

with admiration and awe. Here is a young writer who seems to have been born whole: every hair in place, fingernails filed,

a sharp, mature eye fastened to the world. His prose is laconic, witty, and immensely focused. Reading this collection, I

thought of the young Phillip Roth, who dazzled the world of letters with

Goodbye, Columbus.

Of Salinger, with

Nine Stories.

Gilbert is wonderful. I hope readers flock to these vivid tales."

—Jay Parini

"David Gilbert's strange takes and wonderful dark humor intrude upon the familiar until his own singular vision prevails—he

doesn't let anyone get away with anything."

—Amy Hempel

"David Gilbert has caught us in the act. The tales in

Remote Feed are

swift and entertaining, as invasive as surgery, simultaneously hilarious and terrifying—and dead-on accurate. This is how

we are. What to do?"

—William Kittredge

"To describe David Gilbert as a young writer is deceptive unless the emphasis is placed on writer' rather than young.' These

stories are witty, insightful, even wise; only Gilbert's passion betrays his youth—for most importantly,

Remote Feed

is very definitely not annoying."

—Fran Lebowitz

"These stories stick in the mind like half-remembered dreams: vivid, inexplicable, and full of color. David Gilbert's imagination

seems to live deep down under the skin of our culture, funny and disturbing all at once. A fast and furious first collection."

—Kevin Canty

remote feed

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Normals

remote feed

stories

David Gilbert

BLOOMSBURY

Copyright © 1998 by David Gilbert

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from

the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Bloomsbury

Publishing, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Published by Bloomsbury Publishing, New York and London

Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers

All papers used by Bloomsbury Publishing are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests.

The manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gilbert, David, 1967

Remote feed / David Gilbert.

p. cm.

Contents: Cool moss—Remote feed—Anaconda wrap—Girl with large foot jumping rope—Graffiti—Opening day—Don't go to the basement!—At

the deja vu—Still in motion.

eISBN: 978-1-58234-583-3

1. Psychological fiction, American. 2. Humorous stories, American. I. Title.

PS3557.I3383R46 2005

813,.54—dc22

2005041246

"Remote Feed" originally appeared in

Harper's Magazine,

"Graffiti" in the

New Yorker,

"Cool Moss" in altered form in the

Mississippi Review

and in

New Stories of the South, Best of 1996,

and "Girl with Large Foot Jumping Rope" in altered form in

Cutbank

magazine.

First published in hardcover by Scribner in 1998

First published in paperback by Scribner in 2000

This Bloomsbury paperback

edition published in 2005

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset by Hewer Text (UK) Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in the United States of America

by Quebecor World Fairfield

For my Mother and Father

IT WAS THE summer of theme parties. The Millers started it in June with line dancing. They'd found some group from Texas who

called themselves Get In Line! and we watched and followed these sequined wonders as they stomped through the "Achy-Breaky"

and the "Mason-Dixon." The Bissels tried to top the Millers a few weeks later with a psychic named Francine. She read palms,

tarot cards, was even able to talk to Lena Bissel's greatgrandfather, but like so many spiritualists she had no sense of humor

and did not appreciate Chuck Hubert's zombie walk. Soon after that the Makendricks transformed their annual July Fourth party

into what would have been a spectacular kite party had there been any wind. Laura Makendrick broke into very public tears.

And eventually Zoe and I made a stab at it. We concocted a "Foods of the World" party which quickly turned into a "Drinks

of the World" party. Once again Charlie Hubert performed his zombie walk—a few people always egg him on—and a table was broken,

certainly no antique. I really don't know what it was about that summer, maybe we were all just restless, but normal parties

felt dull and forgetful. Instead, there had to be a something learned even if it was that borscht does in fact taste like

shit and a healthy supply of rum can save almost any party.

Tonight belonged to the Greers, Bill and Tammy. In the inferno of our friends they dwell in the third circle: the friends

of friends with money. Lots of money. I sat downstairs on the couch and waited for Zoe. We were running late but I didn't

care. An awful rumor had spread that there would be no alcohol served, something about false courage and a numbing of the

brain. Yes, I thought, booze will do that to you. Thank God. So I was having a drink which quickly turned into a series of

drinks, all lit with gin. That summer I was drinking gin. But I wasn't smoking.

The television was on and my three-year-old son was propped a few feet from the screen. Static raised his fine blond hair.

The beginning of

Chitty Chitty Bang Bang

was playing on the VCR. Ray loved it. I knew because he had his hands jammed down his elastic pants and he mumbled about cars—"Vroom,

Vroom"—as he squeezed his groin like a toy horn. In May he had discovered the first joy of the pleasure principle. We tried

to thwart this habit by continually slapping him on the wrist and looking angry and pointing a finger to the ever-watchful

sky, but he still carried on, our little boner boy. And nowhere was off limits. Restaurants. Birthday parties. He could pin

the tail on the donkey with one hand. For a while we considered building a cardboard skirt, like the kind that prevents a

dog from scratching his recently pinned ears, at least that's the joke we told gullible friends.

"He'll grow into it," I said to the nervous baby-sitter. She was sitting on the edge of a chair, a knapsack hugging her shoulders.

Her name was Gwen and she had a large head and a large nose. I wondered if the kids at school were merciless toward her. Sombrero

face.

She giggled. I thought of following up with a gag about Dick Van Dyke, but I wasn't sure if she'd even know who Dick Van Dyke

was and I didn't want her to just hear the words "dick" and "dyke." So I offered her a soft drink instead.

"No thanks, I'm fine." She also had a bad complexion. I figured baby-sitting was a relief to her on Saturday nights.

"We won't be late," I told her.

"That's all right. I mean, it doesn't matter." She shrugged her knapsack. "I have lots of work." And she smiled without showing

her teeth. I thought the worst: braces and receding gums.

"And he's easy," I said, gesturing toward my boy. "After this, another video, and if he's still awake after that, pop in another."

I went over to the folding table that acts as our bar and mixed myself another drink. "He's seen them all a hundred times,

the same damn movies, over and over again, but still, you know." My point clinked out in falling ice, and there was silence

except for Truly Scrumptious singing her song. I sat back down. On the floor above I could hear Zoe's maneuverings. I didn't

want to rush her; she was always feeling rushed. It was better to stay quiet than to bitch about being late. Just accept the

situation. And I had that familiar feeling of waiting in an airport lounge for a delayed plane, and the more I waited the

more I became convinced that this plane would crash over Ohio or skid into the ocean and that this drink would be my last

drink and that this moment would be my last memory of things.

Soon Zoe came downstairs and I was relieved to see her. She gave me an expression of exasperation. "Sorry," she said.

"No problem." I lifted my glass to show her that I had been taking advantage of the lag time.

She said to the baby-sitter, "You must be Gwen."

The baby-sitter stood up. "Yes, hello Mrs. Scott."

"Well." Zoe's hands dropped to her sides and she took a deep breath. She was beautiful, tanned from the summer, firm from

jogging, and her hair had recovered some of its youthful blondness. "Just put him to bed when he gets tired. He's had dinner

but if he gets hungry, give him a fruit roll-up. They're in the cupboard." I used to love to watch Zoe think. Her deep-set

eyes have these attractive pouches and when she thinks she seems to search them for misplaced items. "Oh, and the Greers'

phone number is by the kitchen phone, along with the emergency numbers."

The baby-sitter was nodding her huge head. "Got it," she said.

Zoe turned to me. "Okay, we're off." She walked over to Ray and slumped her knees against his back. "Ray, we're going," she

said in a louder voice.

"Yep."

"We'll be back in just a little bit." I knew that Zoe wanted a child that would cry at such departures and wrap helpless arms

around her and wail terribly. But Ray just sat there, hands down his pants, readying himself for a stupid car that could fly.

I ruffled his hair and said, "Have a good time." And as Zoe went toward the front door, I topped off my drink and took it

with me.

" 'Bye now," I said, a bit awkwardly.

The Greers live just far enough away to remind us that we don't live in the truly nice neighborhood. "You know they're not

serving any booze," I said.

"Yes."

"They've got more money than anyone and they're not serving booze. That just doesn't seem right. There's no heavy machinery

involved." Zoe was quiet and looked like a weight lifter before attempting a clean and jerk. "You all right?" I asked.

"I'm not in the mood for a party tonight," she said.

"I hear you. Especially a party without booze." The sky had this grenadine glow. Months earlier a volcano had erupted on some

distant island in the Philippines. A whole village was destroyed, fifty-seven people burned up and blown into the atmosphere—a

definite tragedy—but all that summer every sunset seemed straight out of Hollywood.

"They have a surprise in store." Zoe pushed down the visor and checked her makeup in the pop-up vanity mirror. She wiped at

the corners of her mouth. "I hate surprises," she said.

"Me too." And as we passed under tree-lined streets, I knew that there were eyes on the two of us and that we were somehow

talking to those eyes, a third-party viewer, a witness, a ghost. "Surprises are for suckers," I said. The houses and front

lawns grew progressively bigger. I rolled down the window so that the rushing air could enter our conversation.

"Malachi?"

"What?"

She paused for a second. I thought she was going to say something that would force me to pull the car over and face her. A

hearty dialogue. But there wasn't any melodrama in our life—no affairs, no unemployment problems, no addictions—and we still

thought that people on daytime talk shows were freaks.

We were simply bored.

"What?" I said again.

Zoe reached over and clicked on the radio. The volume was too high but neither one of us bothered to turn it down. And I didn't

drive any faster, just a flat thirty-five miles per hour.

The Greers' driveway was filled with cars and edged with standing torches. We parked on the street along with a few other

late arrivals and followed the bending line of torches to the house: a large neocolonial, white with black shutters. During

Christmas they placed an electric candle in each window. It was quite dramatic. And during Easter they hosted a huge Easter-egg

hunt. They put a hundred bucks in the big egg. Kids would sprint and dive into bushes. But Ray was hopeless, sitting down

and devouring the first chocolate bunny he came across.

"How do I look?" Zoe asked me.

"Fine."

"Really?"

"Yes."

From behind the house we heard a noise. It wasn't a social noise, a mingling of chitchat, music, and laughter; it was more

like an angry swarm of mosquitoes, or, worse yet, a solitary two-hundred-and-fifty-pound mosquito. Mosquito-man. My mind tripped

onto a late-night movie I had recently seen—

The Island of Dr. Moreau

—and I remembered those failed genetic experiments. Boar-man. Weasel-man. Orangutan-man. They terrorized a bare-chested Michael

York. And at two in the morning I rooted for them to rip his body into pretty blond shreds.

"Take my hand," I said to Zoe.

We circled around some bushes, a bit of mulch, a birdbath, and then walked through a gate which opened onto a beautiful back

lawn—almost an acre and a half of perfect Bermuda grass. Off to the side, huddled in a circle, our group of friends hummed

with their heads lowered, their arms intertwined. Just behind them a fifteen-foot stretch of coals glowed hot. It looked like

a strange pep rally.

"Are we playing State tomorrow?" I whispered.

"Maybe it's a barbecue."

We stood still and no one noticed us. No one said, "Hey, it's the Scotts." No one offered us drinks or cheese puffs. No one

cared. The circle was closed, and we didn't want to be one of those pushy couples. Besides, we were late, we didn't have any

party rights. So we just watched as the hum slowly grew around them. A neighbor's dog howled, its timbre much more profound.

And soon the hum reached a breathless pitch, and faces and arms slowly lifted toward the sky as if these people were chanting

refugees waiting for the helicopters to drop down supplies from L. L. Bean. Finally, the hum ended with a lung-emptying

"Ahhh,"

and there was cheering and smiling and one man, a tall guy in a shiny suit, said, "Did you feel the power?" Everyone nodded.

"Yes?" he asked. He glanced around the group. "Well, that's the power of positive thinking." He made a point of training his

eyes on each and every person. "That's the power you hold trapped within your body." He fisted his hands. "The power you never

let out." Raised his finger. "Why?" Paused. "Because of fear."

Still no one noticed us. Attention was focused on this man. He had a manufactured face, smooth and with only a few lines to

delineate a mouth, a nose, eyes. His voice was a personal whisper spoken to a crowd. I was sure he had a set of self-help

videos in the trunk of his car, maybe an infomercial in the works. "Fear," he continued, "is what we have to overcome. Most

of us are still children. We are afraid of the dark, afraid of the unknown, afraid to succeed. Why? Because if we try to succeed,

if we put ourselves on the line, we can fail." I tried to catch the eyes of a few friends by making quick faces, but no eyebrows

raised in recognition.

"Maybe these are the Stepford friends," I said to my wife.

"Huh?"

"You know, Robot people."

"Shhh."

"Now." The man clapped his hands. "I see some new guests have arrived." He gestured toward us like a game-show host displaying

a brand-new washer and dryer. "So I think it's a good time for a break. But remember, let's psych each other up. We're part

of a team." And then, with surprising quickness, he left the group and came over to us. "Hi," he said. "I'm Robert Porterhouse."

"I'm Zoe Scott, and this is my husband Mai."

We shook hands. He had a pinky ring and I hate pinky rings. He also had an expensive gold watch that hung loosely from his

wrist.

"Well, are the two of you ready?" he asked.

"For what?" I said.

He grasped our forearms. "To change your life. To become who you want to be."

I smiled. "A baseball player? Sure."

I could tell by the way Zoe looked at me that she wanted to hit me on the arm, but instead she quickly pushed her voice over

mine. "Why not," she said. I was a little put off by her enthusiasm. We used to laugh at our born-again friends.

"Great, Zoe. You have to align your belief system so that you get what you want."

"Even if it's a bigger house? A Porsche," I said.

"Sure, if that's what you want."

"How eighties," I said.

"No Mai, it's about what you want." He poked the air in front of my chest. "About what's in here." He glanced over our shoulders.

"Now, I've got to check on things. I'll see you in a few." And he walked away.

I turned to Zoe. "And that night, Malachi Scott learned how to live."

"Don't be such a cynic."

I grabbed Zoe by the arms. "Did they get to you too?" I made a plea to the heavens. "You bastards!"

"Jesus, how drunk are you?"

"Not enough for this crap."

"You're going to make a great bitter old man."

"It's the gin. But thanks anyway."

Zoe was once a fan of my banter, thinking it was smart and urbane and very round-table, but now she turned away and made a

disparaging sigh. "So clever," she said.

The circle had broken up and smaller groups formed. Bill and Tammy Greer saw us and waved and came over. Nervous enthusiasm

creased their athletic faces. He was of Norwegian descent. She was of Finnish descent. They both wore the same shade of blue.

"Hey, you guys," Tammy said.

We apologized for being late, then I gave Tammy a kiss, and Zoe gave Bill a kiss, and Tammy gave Zoe a kiss, and Bill shook

my hand. After that, we had little to say.

"So," I said. "What's going on here? A barbecue? A little luau?" I swung my hips.

"No, no," Bill said, shaking his head. "Something a lot more . . . powerful."