Resolute (18 page)

Authors: Martin W. Sandler

Never before had so many ships from various search expeditions spent the winter so near each other. Never had there been such an opportunity to relieve the boredom by exchanging visits and sharing in the usual plays and other entertainment. There was even the opportunity for pranks. It did not take the men of the icebound flotilla long to discover that Penny, skilled and knowledgeable as he was, was almost entirely without humor, totally focused on finding traces of Franklin. One of the highlights of the wintering down was the day on which John Ross and some fellow pranksters placed some weather-beaten planks on the ice near Penny's ships, knowing that the whaler would find them and believe that he had discovered remains of either the

Erebus

or the

Terror.

When exactly that scenario took place, the onlookers from the various vessels could not contain their merriment. Penny was not amused.

But it was not all pranks and entertainment. Far from it. For it would be the searches for Franklin by sledge during this winter that, in addition to the discoveries at Beechey Island, would be the highlight of the unprecedented Arctic activity that took place in 1850â51. After a meeting of commanders, it was decided that while Penny and members of his crew would search Wellington Channel, the major sledging effort would be made to the south and the west by crews from Austin's ships.

Austin put all of the planning for the sledging expeditions in the hands of one of his officers, Leopold M'Clintock, the Irishman who had demonstrated his unique sledging skills during James Clark Ross's 1848 search for Franklin. In the interim, M'Clintock had spent considerable time developing an improved sledge design and ways of equipping the sledges more efficiently. He had also come up with the idea of laying caches of provisions at regular distances as he went so that future parties could increase their range of travel.

Eight expeditions, each traveling in a different direction, would be sent out from the Austin fleet. M'Clintock himself would lead the most ambitious search. During James Ross's expedition, M'Clintock had set a new standard by completing a forty-day sledging exploration. Now he was intending to undertake a search that would keep him away from the ship for twice that long.

After a month of training, the various sledging expeditions set off. One party tried to make its way southeast from Cape Walker (as Franklin had been ordered to do) but found the way ahead completely blocked. Another party made its way down the western shores of Peel Sound. Encountering a fierce blizzard, they turned back, convinced, as other searchers before them had been, that Peel Sound was never free of ice. Their report would only intensify the belief that Franklin could never have gone south and that all subsequent searches should concentrate on the north.

Meantime, M'Clintock and his party were engaged in the longest journey of all. Traveling westward down Barrow Strait they arrived at a point seventy miles beyond that which Edward Parry had reached in 1819. Traveling on, they found the remains of a cart that Parry and his men had used more than thirty years before. Further ahead, at Winter Harbor, where Parry had been trapped, they made a more dramatic discoveryâa huge sandstone boulder, on which was carved an inscription proclaiming the year that Parry had been there. Before leaving the spot, M'Clintock announced that he also had been there by carving the year “1851” on the boulder.

It was now time to turn back. When the men returned to the ship, they had been gone for the exact eighty days for which M'Clintock had planned and had traveled 875 miles. Altogether, the eight sledging parties had covered 7,025 miles on foot and had explored and entered into the map 1,225 miles of previously unknown land. A remarkable achievementâbut they had not found a single trace of Franklin. After the hope engendered by the Beechey Island discoveries, it was becoming a winter of frustration. But it was nothing compared to what the Grinnell expedition had been going through.

AFTER LEAVING BEECHEY ISLAND

, the

Advance

and the

Rescue

had encountered ice everywhere they had turned. Unlike their fellow British searchers, the Americans had absolutely no experience in wintering in the Arctic and De Haven had no intention of doing so; he was heading for home. But first he had to find the

Rescue

, which had become separated from the

Advance

in a storm. Forced to waste precious time, he finally found the sister ship miles away to the west, in Barrow Strait. Taking the

Rescue

in tow, he made a dash for open water. But he was too late. By the time he reached the mouth of Wellington Channel, he could go no further. He had long since lost sight of the British ships. For the men of the

Advance

and the

Rescue

there would be no congenial Union Harbor. They would have to go it alone.

None of the Americans could have even imagined what they would be forced to endure that winter. Even when they wore two pairs of mittens, their hand became frost bitten when they touched any piece of metal. Burning hot coffee froze in their mugs as soon as it was poured. When they tried sucking icicles, the skin peeled off their lips. The only way they could cut butter was with the use of a hammer and a chisel. Their tongues froze to their beards.

Even more seriously, many of the men, including Elisha Kane, had been stricken with scurvy. Several became so weak that any activity caused them to faint. Fortunately, Kane began forcing the crew to regularly eat potatoes and sauerkraut and to drink lemon juice, all rich in Vitamin C, and a major disaster was averted.

Fortunately, when summer arrived, all of the ships were released from the ice. No one was more relieved by the thaw than Austin. Two winters in the ice had been enough. He was ready to return. But not William Penny. He argued vehemently that Austin should lend him one of his steamships so that Penny could continue the search beyond Wellington Channel. “You say we have been acting in concert,” he reminded Austin. “Let us prove the sincerity of that concert. Give me a steamer and with the little

Sophia

I will go miles further.” Austin, who had never warmed to Penny's abrasive personality and who had probably never accepted the presence of a whaler as the captain of a British naval vessel, would not listen. He was taking his fleet home.

For the Americans, there would be one final surprise. Before leaving the Arctic, they suddenly encountered another ship. It was the

Prince Albert

, the vessel that they knew had sailed back to England before the winter had set in. When the captain and second-in-command of the small vessel came aboard the

Advance

it was obvious that they were neither Charles Forsyth nor W. Parker Snow. Instead they were a Canadian, William Kennedy, and a French naval lieutenant, Joseph René Bellot. (Kennedy and Bellot were strange bedfellows, but equally devoted to Lady Jane and the search, see note, page 268.) Lady Franklin, they told De Haven and Kane, bitterly disappointed at the

Prince Albert's

premature return to England, had immediately raised more money, refitted the vessel, and sent it out again to look for her husband. Kane could only shake his head. The noble woman would never give up.

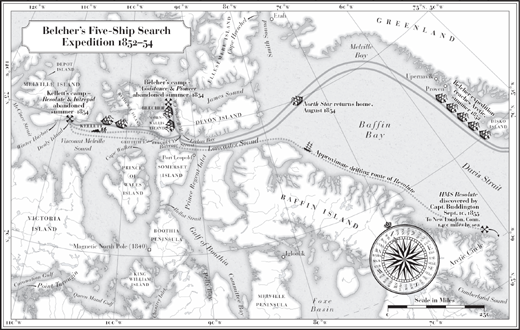

THIS MAP

reveals various locations in the experiences of the Belcher rescue fleet in general, and of the

Resolute

in particular. It shows where the

Resolute

and

Intrepid were

abandoned and where the

Assistance

and the

Pioneer were

left behind. The map also indicates the route along which the

Resolute

drifted after being abandoned, and the spot where whaling master James Buddington discovered her.

CHAPTER 10.

CHAPTER 10.Rescue and Abandonment

“The announcement of relief being close at hand, when

none was supposed to be even within the Arctic Circle, was

too sudden, unexpected and joyous for our minds to

comprehend it all at once.”

â

ROBERT MCCLURE

, on being found, 1853

W

ITH THE RETURN OF AUSTIN

, Penny, and Ross to London in the fall of 1851, only one ship was now left to search for the lost expedition. It would never do. Even the Admiralty recognized that. And now there was additional pressure. Nothing had been heard from either McClure or Collinson. No longer was Jane Franklin alone in her pleadings. Francis Cresswellâthe wealthy and influential father of Lieutenant Samuel Cresswell, second mate and artist aboard the

Investigator

âlaunched a vigorous campaign aimed at reminding everyone that it was not only Franklin and his men who were missing, but that it had also been much too long since his son and his comrades, as well as Richard Collinson and his crew, had been heard from.

The London

Times

summed up the nation's mood when, in an editorial written immediately after Austin's return, it called for an even larger rescue expedition to be sent out:

Though we do not think the geographical importance of these expeditions commensurable with the cost of exposure of a single sloop's crew, we unhesitatingly admit that our obligation to rescue those who have been dispatched on the enterprise of a very different magnitude. It signifies supremely little whether Boothia Felix is a peninsula, an island, or a gulf ⦠but it does impinge most emphatically to our national honour that we should ascertain the fate of our missing countrymen, and redeem them, if living, from the dangers to which they have been consigned.

This time, with far more alacrity than it had displayed when Franklin had first gone missing, the navy acted. It mounted a five-ship rescue expedition. Three of the vessels had been the core of Austin's fleetâthe

Resolute

, now commanded by Captain Henry Kellett, the

Pioneer

, once again commanded by Captain Sherard Osborn, and the

Assistance

, with the expedition's overall commander Sir Edward Belcher aboard. The squadron also included the

Intrepid

, commanded by the recently promoted Leopold M'Clintock and the

North Star

, which would serve as the fleet's supply ship.

The selection of Sir Edward Belcher to head the expedition was based both on his seniority and his official record. On the surface, he seemed a logical choice. The son of a prominent Nova Scotia family, he had joined the navy in 1812, at the age of thirteen, and four years later had served in the campaign against the Barbary pirates. In 1818, as John Franklin was sailing in search of the North Pole, Belcher was promoted to lieutenant and seven years later he sailed with Captain Frederick Beechey in his attempt to link up with the Franklin and Parry passage-seeking expeditions.

Belcher had also distinguished himself as both an explorer and an inventor of a number of nautical devices, including a navigational protractor for fixing a ship's position in coastal water. As an explorer, his accomplishments included the discovery of a number of islands in Norwegian Bay and the first navigation of the Sacramento River. The highlight of his career had been his command of an 1836â42 around-the-world voyage during which he and his crew, in addition to making significant astronomical and meteorological observations, discovered several unknown rivers and a host of previously unknown tropical plants and animals.

On paper, he was certainly qualified to lead what the Admiralty now regarded as the most important rescue mission it had yet organized. But, as events would prove, Belcher was absolutely the wrong man for the job. At fifty-three, he was extremely fit for his age, but he was pompous, quarrelsome, critical of everyone, and arguably the most narrow-minded commander that had ever been sent to the Arctic. Not only did he refuse to listen to the advice of those who had more Arctic experience than he, but he let it be known that he didn't want any officer with him who had served on more than one northern expedition. Fortunately, the Admiralty ignored that wish.