Resolute (32 page)

Authors: Martin W. Sandler

The visit to Captain Potter, if not a fool's errand, had been a major disappointment. But Schwatka was still confident that there were papers to be found on King William Island. On April 1, 1879, Schwatka began his explorations. With three dog teams and seventeen people, including several Inuit women and their children, he set out for King William Island. It would be an incredibly long and difficult trek, one which, as Gilder would describe it, was made possible only by the Inuit hunters:

[There was] only about one month's rations of civilized food for seventeen people, and, was in fact, nearly exhausted by the time we reached King William Land. Our main dependence was, therefore, the game of the country through which we were travelling; a contingency upon which we had calculated and were willing to rely, having full faith in the superior quality of the arms and ammunition with which we had been so liberally equipped by American manufacturers. It is well for us that our faith was well founded, for there can scarcely be a doubt that it was this that made our expedition possible. In all other respects we were probably in a much worse condition than any previous expedition; but the quality of our arms put us at once upon a footing to derive all the benefit possible from the game of the country, a benefit of which we availed ourselves, as the unparalleled score of

522

reindeer, besides musk oxen, polar bears and seals will show. This is what was killed by our party from the time we left Camp Daly until our return. The quality of our provisions was excellent, and it was only deficient in quantity. The Inuit shared our food with us as long as it lasted, and, indeed, that was one of the inducements to accompany us on the journey.

In mid-May, the party encountered its first group of Inuit, an igloo-dwelling tribe known as Ookjooliks. There, from a man named Ikinnelikpatolok, they heard a fascinating story. “We learned at the interview that he had only once seen white men alive,” Gilder wrote in his journal, continuing:

That was when he was a little boy. He is now about sixty-five or seventy. He was fishing on Back's River when they came along in a boat and shook hands with him. There were ten men. The leader was called “Tos-ard-e-roak,” which Joe says, from the sound, he thinks means Lieutenant Back. The next white man he saw was dead in a bunk of a big ship which was frozen in the ice near an island about five miles due west of Grant Point, on Adelaide Peninsula. They had to walk out about three miles on smooth ice to reach the ship. He said that his son, who was present, a man about thirty-five years old, was then about like a child he pointed out

â

probably seven or eight years old. About this time he saw the tracks of white men on the main-land. When he first saw them there were four, and afterward only three. This was when the spring snows were falling. When his people saw the ship so long without any one around, they used to go on board and steal pieces of wood andiron. They did not know how to get inside by the doors, and cut a hole in the side of the ship, on a level with the ice, so that when the ice broke up during the following summer the ship filled and sunk. No tracks were seen in the salt-water ice or on the ship, which also was covered with snow, but they saw scrapings and sweepings alongside, which seemed to have been brushed off by people who had been living on board. They found some red cans of fresh meat, with plenty of what looked like tallow mixed with it. A great many had been opened, and four were still unopened. They saw no bread. They found plenty of knives, forks, spoons, pans, cups, and plates on board, and afterward found a few such things on shore after the vessel had gone down. They also saw books on board, and left them there. They only took knives, forks, spoons, and pans; the other things they had no use for. He never saw or heard of the white men's cairn on Adelaide Peninsula.

Schwatka was exhilarated by the story. If Ikinnelikpatolok was telling the truth, and Schwatka was convinced he was, here was evidence not only of what had happened to at least one of Franklin's ships, but where it had met its fate. Disturbing, however, was the Inuit's account of how, despite all the articles the Ookjooliks had taken from the ship, the books had been left behind.

Moving on towards King William Island, the team came to other Inuit camps, where they heard stories of how certain of the elders had seen white men who were “very thin, and their mouths were dry and hard and black” (sure signs of scurvy). They were also told of how other Inuit had seen tents with dead bodies lying in them, and of how they had also encountered many graves. On the shore of Erebus Bay, just before crossing over to the island, they made one of their most interesting discoveries. “We secured one valuable relic here,” Gilder noted in his journal, “in the sled seen by Sir Leopold McClintock, in Erebus Bay, which at that time had upon it a boat, with several skeletons inside. Since the sled came into the hands of the Inuits it has been cut down several times. It was originally seven feet longer than at present, the runners about two inches higher and twice as far apart. But even in its present state it is an exceedingly interesting memento. We have carefully preserved it in the condition in which it has been in constant use by the Esquimaux for many years.” Aware of the interest that such a relic would have for the Smithsonian, which had partially sponsored his venture, Schwatka had his men pack up a remaining section of the boat to be taken back with him to the museum.

It was indeed a most valuable find, but it would be followed shortly thereafter by the most disturbing story that Schwatka, Gilder, or any of the others would hear during the entire expedition. It came from an Inuit named Ogzeuckjeuwock, who told them that several years before he had visited the site of one of the boats that the Franklin party had abandoned, where he had found skeletons and many relics. The native's story, confirmed by others in his tribe, not only provided Schwatka with the most probable explanation of what had happened to the sought-after books and papers, but also once again raised the ugly specter of cannibalism. “Ogzeuckjeuwock,” Gilder wrote, “said he saw books [in a long boat on the island] in a tin case, about two feet long and a foot square, which was fastened, and they broke it open.” Gilder continued:

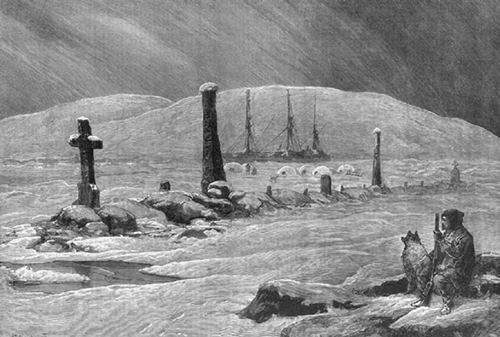

BOTH THE LONG SEARCH

for the Northwest Passage and the years of seeking the men of the Franklin expedition engendered hundreds of depictions of events that took place during these quests. Most were drawn by artists or individuals who took part in the happenings. Fanciful depictions also appeared, such as this one of Schwatka or one of his men gazing at a row of graves and mammoth headstones never proven to have existed.

The case was full. Written and printed books were shown him, and he said they were like the printed ones. Among the books he found what was probably the needle of a compass or other magnetic instrument, because he said when it touched any iron it stuck fast. The boat was right side up, and the tin case in the boat. Outside the boat he saw a number of skulls. He forgot how many, but said there were more than four. He also saw bones from legs and arms that appeared to have been sawed off. Inside the boat was a box filled with bones; the box was about the same size as the one with the books in it.

He said the appearance of the bones led the Inuits to the opinion that the white men bad been eating each other. What little flesh was still on the bones was very fresh; one body had all the flesh on. The hair was light; it looked like a long body. He saw a number of wire snow-goggles, and alongside the body with flesh on it was a pair of gold spectacles. (He picked out the kind of metal from several that were shown him.) He saw more than one or two pairs of such spectacles, but forgot how many. When asked how long the bodies appeared to have been dead when he saw them, he said they had probably died during the winter previous to the summer he saw them. In the boat he saw canvas and four sticks (a tent or a sail), saw a number of watches, open-faced; a few were gold, but most were silver. They are all lost now. They were given to the children to play with, and have been broken up and lost. One body

â

the one with flesh on

â

had a gold chain fastened to gold ear-rings, and a gold hunting-case watch with engine-turned engraving attached to the chain, and hanging down about the waist. He said when he pulled the chain it pulled the head up by the ears. This body also had a gold ring on the ring finger of the right hand. It was taken off, and has since been lost by the children in the same way that the other things were lost. His reason for thinking that they had been eating each other was because the bones were cut with a knife or saw. They found one big saw and one small one in the boat; also a large red tin case of smoking tobacco and some pipes. There was no cairn there. The bones are now covered up with sand and seaweed, as they were lying just at high-water mark. Some of the books were taken home for the children to play with, and finally torn and lost, and others lay around among the rocks until carried away by the wind and lost or buried beneath the sand.

Here then was the answerâalbeit an enormously disappointing oneâthat Schwatka had been seeking. It was supreme irony. Records of the most advanced search for the Northwest Passage that had ever been launched had been casually destroyed by children who could not even read them. Others had been either blown or washed away. Assessing the enormity of what had been lost, Gilder stated in his journal: “It isâ¦a very natural deduction that the books that were found in a sealed or locked tin case, which had to be broken open by the natives, were the most important records of the expedition.”

A frustrated Schwatka was ready to go home. But first there would be two other discoveries. Coming upon a large mound of earth, Frank Melms and Henry Klutschak quickly discovered that it was a grave. Describing the burial site in his account of the journey, Schwatka wrote:

It was obvious that it had been opened and despoiled by the natives some years before. Frank and Henry had examined it closely enough to uncover a silver medal, which they brought back with them. It was about three inches in diameter. On one side was the bust of King George IV, surrounded by the inscription: “Georgius IIII., D. G. Brittanniarum Rex, 1820,” and on the reverse was a laurel wreath surrounded by the inscription: “Second Mathematical Prize, Royal Naval College.” Inside the wreath was cut “Awarded to John Irving, Midsummer, 1830.” This then, was the resting place of Lieutenant Irving, third-ranking Lieutenant on the

Terror,

the second of Sir John Franklin's ships.

The party's second major discovery before returning to Camp Daly was made in late July. “Lieutenant Schwatka found a well-built cairn or pillar seven feet high, on a high hill about two miles back from the coast, and took it down very carefully without meeting with any record or mark whatever,” Gilder wrote in his journal. “It was on a very prominent hill, from which could plainly be seen the trend of the coast on both the eastern and western shores, and would certainly have attracted the attention of any vessels following in the route of the âErebus' and the âTerror', though hidden by intervening hills from those walking along the coast.” Schwatka had rediscovered the cairn that had so puzzled Penny, Kane, and its other original finders. Schwatka and Gilder added their own speculation as to why there had been no message in the cairn. “The next day Frank, [Hannah], and I went with Lieutenant Schwatka to take another look in the vicinity of the cairn, and to see if, with a spy-glass, we could discover any other cairn looking from that hill, but without success,” Gilder continued. “It seemed unfortunate that probably the only cairn left standing on King William Land, built by the hands of white men, should have no record left in it, as there it might have been well preserved⦠The inference was that it had been erected in the pursuit of the scientific work of the expedition, or that it had been used in alignment with some other object to watch the drift of the ships. Before leaving we rebuilt the cairn, and deposited in it a record of the work of the Franklin search party to date.”

It was now late September 1878, and it was, Schwatka felt, truly time to start back. The almost six-month return trip to Camp Daly was as demanding as the trek to King William Island had been, made even more so, in fact, by the extreme temperatures. (Frigid coldness was not the only environmental extreme with which Arctic explorers had to contend; see note, page 277). Schwatka noted the details of the harrowing trip in his journal:

It was on January 3, 1880, when Henry Klutschak noted that the thermometer had reached 71 degrees below the freezing point, coldest on the trip and the coldest I believe ever experienced by white men in the fieldâ¦That low temperature was not at all disagreeable, until long towards the early night when a light breeze from the south sprang up. It is not so much the intensity of the cold that determines the dangerous character of Arctic weather as it is the strength and direction of the wind. I have found it far pleasanter for travelling, hunting or sledging, with the thermometer at 60 to

70

degrees below zero, with little or no wind blowing at the time, than to face a rather stiff breeze when the little tell-tale showed a far warmer temperature.

At any temperature below zero the beard must be kept closely cut, or it will form a base for a congealed mass of annoying ice, and from 60 to

70

degrees below zero, the accumulation glues the lips and nostrils together in the most diabolical manner. The few scattering bristles that the Esquimaux grow give them quite an advantage over the full bearded Caucasian, whose flowing whiskers are decidedly more ornamental than useful.