Resolute (27 page)

Authors: Martin W. Sandler

To Hobson, the discovery of the skeletons, grisly as it was, was not a complete surprise. Given the note he had found, he half expected to find the remains of members of the Franklin party. What

was

astounding, however, was the nature of the articles in the boat and their accumulative weight. None of the items could be considered essential for men trying desperately to save their lives. And why in the world would they go out of their way to load the boat with so much weight when to pull it in their weakened condition would likely sap whatever energy they had left? It was yet another mystery that would never be solved, another puzzling enigma of the Franklin saga.

And it wasn't the only mystery connected with the boat. Once he started to get over his amazement at the vessel's cargo, he noticed the direction in which the boat was pointed. It was headed directly away from “Back's Fish River,” where, according to Crozier and Fitzjames's note, the Franklin survivors were headed. How could that be explained?

That was not all that Hobson did not know. What he had no way of realizing was that buried directly beneath where he and his party were standing were the bones of fourteen other members of the Franklin expedition. Years later, they would be uncovered by other searchersâand would reveal a terrible secret. From the knife markings on the bones, it would be obvious that the most edible parts of the bodies had been carefully stripped away. Investigation would also reveal that the jaws of the unfortunate deceased had been carved away from their skulls, an indication that their brains, rich in protein, had been extracted. John Rae's report of cannibalism had not been mere Inuit fantasy.

His explorations completed, Hobson headed back to the

Fox.

M'Clintock, not knowing what his lieutenant had discovered, continued to follow Hobson's route. Crossing Cape Herschel, he came upon the gigantic cairn that Peter Dease and Thomas Simpson had erected during their 1839 discovery-filled explorations. Twelve miles from there he found a cairn that Hobson had left behind, containing a message describing the note he had found. On May 29, he spotted the lifeboat.

If anything, M'Clintock was even more shocked at the vessel's contents than Hobson had been. Later he would describe the boat and what had been packed inside it as “a mere accumulation of dead weight, but slightly useful, and very likely to break down the strength of the sledge crews.” Telling himself that perhaps another explorer would some day be able to solve that part of the Franklin puzzle, M'Clintock realized that it was time to head back to the

Fox

and sail for home.

He arrived back in England during the third week of September and was hailed for having led the expedition that had finally uncovered the secrets of John Franklin's fate. Among the honors that were bestowed upon him was a request by Queen Victoria that he sail the

Fox

to her residence at the Isle of Wight, where she could personally congratulate him and view the relics he had brought back with him. (Queen Victoria inspired decades of British Arctic explorers during her sixty-three-year reign; see note, page 274). For his discoveries, William Hobson was promoted to the rank of commander. He would never realize how close he had come to proving that John Rae's report of cannibalism had sadly been all too true.

CHAPTER 14.

CHAPTER 14.Still Searching

“I felt that I had within my grasp the great and noble

thing which had inspired the zeal of the sturdy Frobisher,

and that I had achieved the hope of the matchless Parry.”

â

ISAAC HAYES

, 1861

T

HE DISCOVERIES MADE

by Hobson and M'Clintock satisfied the Admiralty that, although many questions remained, the fate of Franklin and his men had been revealed. There would be no more British naval searches. Nor would Lady Franklin have the resources to mount further explorations. The Americans, on the other hand, viewed the British withdrawal as a golden opportunity.

There were indeed questions that still remained: Were there survivors of the Franklin party still out there, perhaps among the Inuit? What about the journals and other records of the expedition? The passage had been found, but the other great prize, the North Pole, still beckoned. There was still great glory to be gained and there were Americans determined to make it their own.

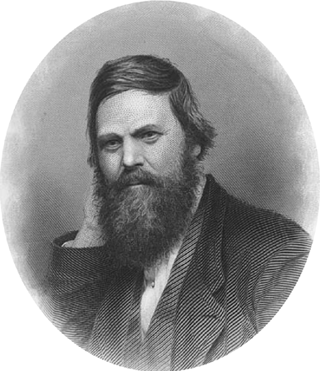

Chief among them was Charles Francis Hall. The Arctic quests had featured more than their share of distinctive characters. Now the world was about to be introduced to perhaps the most unique of them all. Born in New Hampshire in 1821, Hall, a former blacksmith and owner of a small Cincinnati printing firm, was fascinated by everything about the Arctic. He had read every book and article about the region he could find. He had studied the reports and journals of all the previous expeditions, especially those of Elisha Kane, who was his hero. Unlike the frail Kane, however, the full-bearded, broad-shouldered Hall was the picture of good health. He was only five feet, eight inches tall and weighed two hundred pounds, but all of it seemed to be muscle. Above everything else, Hall had become fascinated with the Inuit.

He could not understand why, from the beginning, the British had not made a far greater effort to learn all they could from the natives. This was particularly true, he felt, of M'Clintock and Hobson. Their discoveries could not be dismissed; they were certainly the most significant yet. But why, once they had proven that King William Island was the key to unlocking the Franklin mystery, hadn't they spent more time questioning the natives? Why hadn't they combed the entire island and the surrounding area for survivors?

That is just what Hall intended to do. And, along with everything else, he had his own special motivation, one that he was not reluctant to reveal. He had received a message from above. God had come to him and told him that it was his destiny to find the Franklin survivors. He would go, and he would go as soon as possible. He knew that Isaac Hayes, the doctor who had accompanied Kane, was planning his own expedition. Hall was determined to beat him to the Arctic.

Early in the spring of 1860, Hall, having sold his business and left his pregnant wife and daughter behind, traveled to New York to seek funding for his heaven-endorsed mission. There he met with the most logical funder, Henry Grinnell, who was once again willing to put up money for an Arctic quest. But not anywhere near what Hall had hoped for. He had asked for two fully equipped ships. What he got instead was free passage aboard a steam whaleship and a quantity of supplies.

DRIVEN BY THE BELIEF

that he had been personally selected by the Almighty to find the survivors of the Franklin expedition, Charles Francis Hall, through his amateur, independent expeditions, proved that it was possible for a white man to live in the Arctic for long periods of time. His untimely death added to the many mysteries attached to the Franklin saga.

Disappointed but hardly discouraged, Hall revised his plans. Once the whaleship deposited him at Baffin Island, he would spend the winter living with the Inuit, hopefully even learning their language. Then, in the spring, he would travel by boat to King William Island and make his discoveries. It was an unprecedented scheme. No explorer, not even John Rae, had ever lived alone with the Inuit for an entire winter.

Hall left for the Arctic on May 20, 1860. The whaleship upon which he was being carried was the

George Henry

âthe same vessel James Buddington had used to rescue the

Resolute.

And the coincidences did not stop there. The captain of the

George Henry

was Sidney Buddington, James's nephew and the tender that had been sent to accompany the

George Henry

was the

Rescue

, the same vessel that had been part of Elisha Kane's first search for Franklin.

The

George Henry

arrived off the coast of Baffin Island in the middle of August and Buddington anchored her in what was then called Frobisher Strait, discovered by the early Arctic explorer Martin Frobisher some 285 years before. (Once Hall discovered that this body of water was actually a bay, it became known as Frobisher Bay.) At once, Hall realized that all he had read about the wonders of the North had not been exaggerated. The first iceberg he saw “appeared a mountain of alabaster resting calmly upon the bosom of the dark blue sea.” Surveying the landscape, he felt that the mountains were “like giants holding up the sky ⦠Never did I feel so spellbound to a spot as that whereon I stood.”

His exhilaration was short-lived. Within days a horrendous storm struck the area. The

Rescue

was torn from its mooring and although its crew was saved, the vessel was completely destroyed. Somehow, Buddington was able to maneuver the

George Henry

out of the teeth of the storm and find haven in Rescue Harbor off Cumberland Sound. There the ship would remain for the rest of the year.

It was an early disaster, one that might well have diminished the spirit of even the most seasoned Arctic adventurer. But not Hall. “I was determined,” he later wrote, “that, God willing, nothing would daunt me; I would persevere if there was the smallest chance to succeed. If one plan failedâif one disaster came, then another plan should be tried.”

First he had to wait out the winter. And on November 2, an event occurred that would alter the rest of his days in the Arctic. As he sat in his cabin aboard the

George Henry

, an Inuit woman suddenly appeared. Introducing herself as Tookoolito, and telling him that the white man called her Hannah, she explained that she and her husband (known to the white man as Joe Ebierbing) had in the past worked with British whalers; these white men had even taken the two of them to London, where they had been presented to the Queen. Would Hall, she wanted to know, like to have the couple join him as guides and interpreters? It would be the beginning of a relationship upon which Hall would depend for the rest of his life.

In Hannah and Joe, who spoke English fluently, Hall saw his golden opportunity to learn to live like the Inuit. Guided by them, he lived for almost another full year among the natives who were camped nearby, discovering how to sustain himself on seal blubber and blood, and learning how to hunt and drive dogsled teams in temperatures dozens of degrees below zero. Later, Hall would describe his life in the camp as “charming for all its lack of civilized trappingsâor perhaps because of its lack.” (In encountering the Inuit, those who went searching for Franklin came face to face with a culture that was totally foreign to them; see note, page 275.)

LIKE HER HUSBAND

Joe Ebierbing, the Inuit woman Tookoolito (Hannah) served Charles Hall faithfully on all three of his Arctic expeditions.