Resolute (26 page)

Authors: Martin W. Sandler

Finally freed from the ice, M'Clintock and his men spent the entire summer of 1858 beginning their search, but found nothing. When the ice returned, they were forced to seek winter quarters, this time under much more favorable circumstances in the harbor at Port Kennedy, at the west end of Bellot Strait. In late February 1859, on one of the several sledging expeditions he and Hobson launched from the

Fox

, M'Clintock made his first discovery. At Cape Victoria, on the west coast of Boothia Felix, he came upon a group of Inuit, one of whom was wearing a British naval button. And the natives had a story to tell.

The Inuit told of two ships, one that had been sunk and another that had been crushed by ice, and of white men who had starved to death on an island somewhere to the southwest, a location that M'Clintock realized had to be King William Island. And, like the natives that John Rae had encountered some five years earlier, the Inuit had objects that perhaps M'Clintock would like to buyâneedles, buttons, a gold chain, silver spoons, and forks. Most revealing were the knives the Inuit showed him. They had obviously been fashioned from wood and metal from a wrecked ship. Finally, the natives handed M'Clintock a silver medal, which, according to its inscription, had belonged to Alexander McDonald, the assistant surgeon aboard the

Terror.

For M'Clintock, the Inuit's stories were a confirmation of what he had believed was the key to his search. More than ever, he was convinced that the answers he was looking for were to be found at King William Island. After returning to the

Fox

, he and Hobson set out with sledge parties to search the shores of the island. They left on April 2, and within a few days encountered another group of Inuit who told the same story of two ships, one having been sunk, the other having been driven ashore by the ice. These natives also had items that clearly had come from the

Erebus

and the

Terror.

By April 26, M'Clintock, Hobson, and their men had reached Cape Victoria, where M'Clintock decided that they should split up. He would explore southward down the east coast of King William and then travel clockwise around the island; Hobson was to head directly to the west coast to confirm the Inuit's story of a ship having been forced ashore there.

On the seventh of May, M'Clintock came upon an Inuit village whose inhabitants also had significant items. Among them were spoons and forks bearing the crests or the initials of various

Erebus

and

Terror

personnel, including John Franklin and Francis Crozier. To M'Clintock's disappointment, despite all of the articles he had recovered, he had still not been shown a journal, a diary, or a single scrap of paper, parts of the record of the lost expedition that Franklin would certainly have compiled.

The disappointment turned into dismay when, before leaving the camp, M'Clintock was told yet another story by an elderly Inuit woman. She had seen a large group of white men slowly making their way on foot towards the Great Fish River. Many of these men had suddenly dropped in their tracks; some, she stated, had been buried; others had remained where they collapsed. It was still not evidence that he had seen for himself, but it was certainly the most devastating report he had yet received.

Leaving the settlement, M'Clintock continued south where, in another Inuit village, he saw wooden kayak paddles, spear handles, snow shovels, and tent poles. There were no trees for hundreds of miles and it was obvious to M'Clintock that the wood that had gone into the making of these items had come from the remains of a ship. A few days later he was at Montreal Island, but his explorations revealed only an empty meat tin and some pieces of copper and iron. Again, none of the hard evidence he was looking for.

M'Clintock then turned west and headed back to King William Island. There, on May 25, he made his most important find. Having decided that perhaps his next best course of action would be to follow the route he had ordered Hobson to take, in order to find out what, if anything, his lieutenant had been able to discover, he suddenly came upon a human skeleton lying face down on the frozen terrain. Close by lay a clothes brush, a pocket comb, and a notebook. A quick inspection of the book revealed that the unfortunate soul had been Harry Peglar, one of the

Terror's

officers. It was an important findâthe first direct evidence of what M'Clintock was becoming increasingly certain had been a major disaster.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant William Hobson was having a terrible time of it. The several explorations he had engaged in while the

Fox

had been beset in Bellot Strait had only increased his intense dislike of sledgingâthe bone-numbing cold, the inevitable storms, the nights trying to sleep in inadequate tents. And this trip had already become the worst of all his sledging experiences. His menâfour seamen and an Inuit guideâwere suffering terribly. Since leaving the

Fox

some thirty-four days before, the temperature had averaged about 30 degrees below zero. Every one of his men had frostbite. He worried most about Thomas Blackwell, the ship's surgeon. His lower extremities had turned completely white and he had almost no feeling in them. Periodically the men would stop and attempt to warm the doctor's feet with their hands. Hobson didn't dare think of what lie ahead for Blackwell even if he was fortunate enough to return to the

Fox.

In many ways, Hobson himself was in equally bad shape. His legs were so swollen that he could hardly walk. Most frightening, his skin had become severely blotched, his joints ached, his gums bled, and he was shaken with chillsâall unmistakable signs of scurvy. And, as if that were not enough, he, like almost all his companions, had developed snow blindness from the brilliant, eighteen-hour-a-day Arctic sun. He could barely see.

Suddenly, after making his way up a rugged coastal point, he thought he saw something. His eyes were watering terribly; the landscape was appearing to him in varying colors and much in front of him seemed to be coming out of a haze. But he was sure he had seen

something.

Or was it one of the Arctic mirages? He was all too aware of John Ross's imaginary Crocker Mountains.

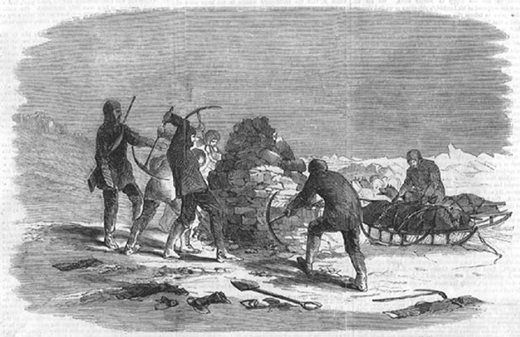

LEOPOLD M'CLINTOCK'S

sledging expertise never served him better than during his discovery-making voyage in the

Fox.

Here, he approaches the cairn where his lieutenant William Hobson first found the note left behind by members of the Franklin expedition.

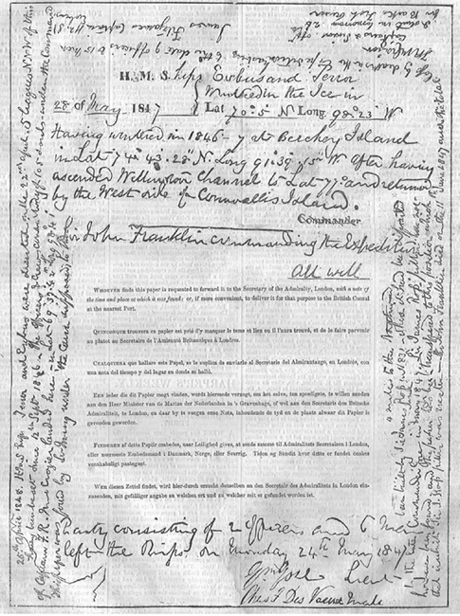

WILLIAM HOBSON

and members of his party tear apart the cairn containing the note revealing Franklin's demise. Within weeks of the

Fox's

return to England, publications such as the

Illustrated London News

and

Harper's Weekly

featured dramatic depictions of the expedition.

But it

was

something, something extraordinary. There, towering above the sea was a six-foot-tall stone cairn. Around it were five-foot-high mounds of clothing, blankets, mattresses, and other articles. There also were pans, kettles, and four of the type of iron stoves used on British navel vessels. Now working feverishly to clear his eyes, Hobson then discovered that the entire area was littered with scores of other objectsâshovels, pickaxes, saws, and barrel hoops, all partially covered by the snow. Further on there were rusted meat tins and broken bottles, all bearing the symbol of the Royal Navy. There was no doubting itâall that he was looking at had been part of the Franklin expedition.

But a closer examination of these items would have to come later. He could not wait to tear apart the cairn. Almost as soon as he began, a sealed tin fell out at his feet. Inside was a single sheet of Admiralty record paper. Upon it was an official message printed in six languages. It read “WHOEVER finds this paper is requested to forward it to the Secretary of the Admiralty, London, with a note of the time and place it was found.” Above and below this standard message, was a handwritten note which stated:

28 of May 1847. H.M.S.hips

Erebus

and

Terror

Wintered in the Ice in Lat.

70

°5'N Long. 98°23'W. Having wintered in 1846â7 at Beechey Island in Lat 74°43'28” N Long 91°39'15” W. After having ascended Wellington Channel to Lat 77° and returned by the West side of Cornwallis Island. Sir John Franklin commanding the Expedition. All well Party consisting of 2 Officers and 6 Men left the ships on Monday 24th May 1847.

â

Gm. Gore, Lieut., Chas. F. DesVoeux, Mate

Hobson was now trembling, for he knew that he had found the first written record of the Franklin expedition. And although it had been penned almost exactly twelve years earlier, it was hopeful. “All well,” it had ended. But what was the handwriting that ran all around the margins of the paper? Quickly he read it. And it was crushing. Written almost a year after the first note, it read:

April 25th, 1848

â

HM's Ships

Terror

and

Erebus

were deserted on 22nd April

, 5

leagues N.N. W, of this, having been beset since 12th September 1846. The Officers and crews, consisting of 105 souls, under the command of Captain F. R. M. Crozier, landed here in Lat. 69°37'42” Long. 98°41'â¦Sir John Franklin died on 11th of June 1847; the total loss by deaths in the Expedition has been to this date 9 officers and 15 men.

â

James Fitzjames, Captain HMS

Erebus

â

F. R. M. Crozier, Captain and Senior Officer

And start tomorrow, 26th, for Back's Fish River.

Hobson was devastated. John Franklin was dead. And, given the information contained in the marginal note, how could he even hope that anyone in the lost expedition could still be alive? But despite his own ever-weakening physical condition and that of the rest of his party, he kept on searching, following the route along the island that he was now certain the survivors of the Franklin party had taken. At this point the effects of his scurvy were so bad that his teeth were beginning to fall out and he was so weak that at times he had to be pulled along in the sledge. By May 11, he decided it was folly to go on. They had to turn back.

IT WAS ONLY

one page long and its most important information was scribbled all around its edges. Yet, the note containing two messagesâthe first dated May 28, 1847 and the second dated a year laterâwas the single most important piece of written evidence in the search for Franklin and his men.

But just as he started to do so, he made another unexpected discovery. There on the coast lay the largest lifeboat Hobson had ever seen. Together with the huge sledge upon which it rested, it had to weigh at least fourteen hundred pounds. What was inside the boat stunned him even more. Lying at the bottom of the vessel, which he now realized was the type of long, narrow vessel that both the

Erebus

and the

Terror

had carried, were two skeletons, one at the bow, the other at the stern. Between the two skeletons was an astounding array of articlesâbooks, slippers, cigar cases, tooth brushes, various kinds of footgear, assorted toolsâeven a collapsible mast and sails. The only provisions were some loose tea and about forty pounds of chocolate.