Reverse Deception: Organized Cyber Threat Counter-Exploitation (102 page)

Read Reverse Deception: Organized Cyber Threat Counter-Exploitation Online

Authors: Sean Bodmer

Tags: #General, #security, #Computers

When these stolen documents were transferred to Julian Assange, the status value of those documents transferred as well. During the early days following the discovery of the theft of the documents, the case sounded very much like one that was motivated by cause. Many of Assange’s public statements had themes that revolved around disclosing the secret machinations of governmental and military entities as a means to coerce these organizations into behaviors that he and his followers felt were more ethically correct.

However, there were a number of signs that what was motivating Assange was not cause but status. One of the most important clues was the hesitancy to divulge all of the documents at once, but rather to dribble them out in small chunks. When an individual or hacker holds information that has status value, if he publicly discloses that information, it loses its status value because it is no longer secret or closely held. If Assange had been motivated by cause, then he would have been much more likely to release all of the documents at once in order to cause maximum embarrassment and thus enhance the chances that the disclosure would have a real effect on the governmental entities involved. Instead, he released them in smaller chunks so that he would only partially “spend” the status value of the documents with each release.

Status as a motivation can also be put to effective use in an offensive capacity. As noted earlier, the formation, maintenance, and communication of status hierarchies within hacking groups are often problematic. One consequence of this is that from a status perspective, these groups are not very stable. It does not take much discordant information to cause significant rifts within the group. For example, if inconsistent status information about a targeted group member (such as the group leader) is introduced into the communication channels, the result can be the initiation of considerable conflict that can lead to the serious disruption of the group’s activities and plans. This inconsistent status information might be introduced by manipulating another group member to denigrate the skills of the target in an e-mail or IRC communication, which in turn is leaked to other group members, as well as the hacking community at large.

Motivational Analysis

Now that we have discussed the six motivations associated with malicious online behavior, let’s see where an understanding of these motivations can be useful to profilers.

A very useful application of motivational analysis is the evaluation of the assets of an enterprise to see what servers have what kind of value to which kind of individual. This allows information security personnel to prioritize how resources are spent in the defense of the network and its servers. Using the six motivations as a simple taxonomy, each device within the enterprise can be coded in terms of the likelihood of attack motivated by each motivation. This kind of analysis may be useful in gauging the current threat environment in terms of the motivation of known actors and attacks in play, so that resources can be shifted to protect those assets that appear at greatest risk at the moment.

Another example involves the status value of stolen data or documents, which was discussed in the previous section. Imagine that you are a secret government agency, and over the weekend, a server was compromised and sensitive documents were copied and spirited outside the network to an unknown location by an unknown actor or actors. While the technical personnel patch the security hole that allowed the intrusion to take place, the reaction from senior managers at the agency may be one of resignation to the fact that the documents are now no longer secret.

The dilemma faced by senior management may not be as straightforward as it seems. It depends on the motivation of the actor or actors who committed the crime. If the motivation of the actors was one of cause, then it is likely that the documents will not remain secret very long. The documents probably will be exposed in the press at the first opportunity, or they may be on their way to a foreign power’s intelligence apparatus. However, if the motivation of the intruders was one of status value, there is a chance that all is not lost. Remember that these secret documents lose their status value when they are disclosed or copied and distributed to others. They retain their status value only as long as they remain secret and in the custody of the original perpetrators. This means that the government agency has a window of opportunity—albeit usually a small one—to assemble a technical team, put as many clues together as quickly as possible, and attempt to identify and apprehend the perpetrators while they are still sitting on the documents.

If the organization fails to apprehend the individuals in time, there is still value to the motivational assignment process. The idea here is to think of ways that you can alter the status value of the stolen assets. One possibility is to disclose the essence of the documents before the perpetrators can, in a manner that minimizes the collateral damage to the original owners of the data. Another strategy may be to generate a story around the documents that suggests that the information in them is false or misleading, and that this was done intentionally for purposes that are not going to be disclosed.

A third application of motivational analysis is the idea of tuned honeypots. A tuned honeypot system is a series of computers, each of which houses a different kind of information. If you want to understand the motivations of individuals who are attempting to compromise your network, placing a set of tuned honeypots within your enterprise can assist in providing more information about the potential motives of the attackers.

Imagine a military installation that installs a tuned honeypot system to help determine the motivations of a specific APT that has been observed attempting to compromise a particular network. One server in the tuned honeypot system might house a real-looking but fictitious e-commerce server for the base PX that would be attractive to individuals whose motivation is money. Another server might contain some real but stale troop movement and logistics information that would be attractive to individuals working for a foreign nation-state intelligence service. A third server might hold documents that contain false information about something that might otherwise embarrass the government but can be disproven as disinformation if it is ever compromised. By watching how the individuals behind the APT move around the tuned honeypot system and observing which files they examine and take, you can construct an educated hypothesis about their motivations.

A proactive example application of motivational profiles takes advantage of the nature of strong meritocracy within the hacking community, and more specifically, within a targeted hacking group itself. Given the strong presence and maintenance of the status order within the targeted group, efforts that disturb this status hierarchy can serve to disrupt the structure of the group and social relationships within that group, thus reducing its stability. This often involves the introduction of inconsistent status information concerning one or more members of the group. This technique targets the higher status, more skilled individuals in the hacking group. It may involve the public disclosure of a vulnerability in the code that the target individual has developed or the p0wning of a system that the high status target individual owns. Efforts that introduce inconsistent (for example, lower) status information about high-status individuals within the hacking group increase the likelihood of status conflicts within the group, which will strain social relationships among its members. This strategy has been effectively deployed by at least one entity within the global intelligence community.

A somewhat different approach based on similar principles could be applied to a cyber criminal gang. Recall that one of the tensions that develops within these groups results from the introduction of money as a competitive status characteristic. Aside from technical skills, status position within a cyber criminal group can depend on the amount of money the member possesses or extracts from the criminal enterprise. If the conflict revolving around which status characteristics—technical skills or money—can be amplified through a defender’s communications is directed to specific members of the cyber criminal group, then it may be possible to destabilize the cyber gang along technical and monetary issues.

Social Networks

Social networks are an incredibly data-rich and important profiling vector, especially when it comes to objectives such as identification, pursuit, and prosecution. Social networks often give profilers direct clues about many different dimensions of an individual’s life. These clues allow them to produce a very detailed profile of an individual, as well as make inferences about those individuals beyond the information present on their social networking pages.

What information sources might provide data that could be found in a typical social networking analysis? Data of this type is usually found in the form of exchanges or relationships between actors. For example, a series of IRC chats may be harvested to map the flow of message exchanges between a set of actors of interest. In another example, a profiler may extract information from the pages of online social networking websites themselves to populate a social networking analysis data matrix.

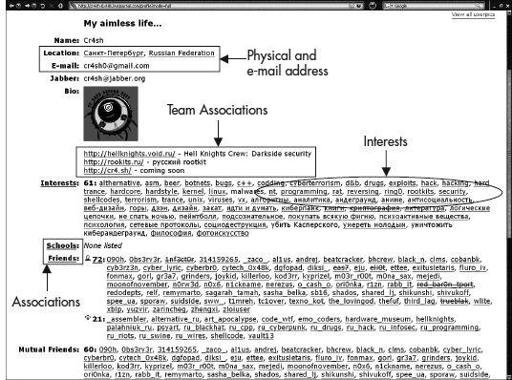

Figure 10-1

is an illustration of a LiveJournal social networking page for a member of a Russian hacking crew from a recent study (Holt et al, 2009).

Figure 10-1

Example of a hacker’s LiveJournal web page

Notice that the webpage lists the following information about this crew member:

A rough geolocation

An e-mail address

A list of the hacking groups or crews that he is associated with

A list of his interests