Richard The Chird (41 page)

Authors: Paul Murray Kendall

British Museum

Parchment with signatures "£D-WARDUS QUINTUS" above, "Loy-aulte me lie, Richard Gloucestre" in the center, and "Souvente me souvene Harre Bokingham" below.

The Hall of Crosby's Place, Richard's town house in Chelsea.

National Buildings Record

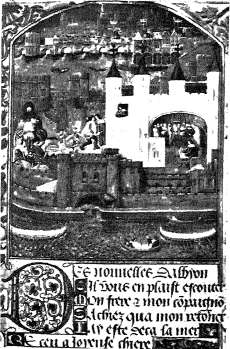

The Tower of London with old London Bridge in the background. A miniature from a manuscript of the poems of Charles d'Orleans, who was captured at Agincourt in 1415 and remained a prisoner in England until 1440.

Ifixw cnyfaijt {jmitir w frttt i -^

''"^SHS*

British Museum

York Minster, scene of the investiture of Richard's son Edward as Prince of Wales.

National Buildings Record

National Portrait Gallery, London

Lady Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry VII.

Stewart Bale, Ltd., Liverpool

Thomas, Lord Stanley.

National Portrait Gallery, London

Henry VII.

were quarreling with one another. The Scots, however, were now showing signs of tiring of the warfare which had brought them little but hard knocks. On August 16, James the Third sent Richard a proposal for an eight months' abstinence of war with a view to permanent peace—"a courteous and wise letter/ 1 Bishop Langton called it. Richard showed his willingness to negotiate by offering to provide safe-conducts for a Scots embassy. Still, none knew better than he how weak and vacillating King James was. He confirmed Earl Douglas' annuity of five hundred pounds and he supported at his court the Duke of Albany, who had once again betrayed his brother, delivered Dunbar to the English, and fled across the border. If the Scots continued to make trouble, Douglas and Albany would be sent north to keep them busy. 13

Irish affairs also demanded Richard's attention. By coining silver money similar in appearance to that of England but worth much less because it w r as heavily alloyed, the Irish were visiting serious financial losses on English merchants. Richard therefore ordered that money was to be minted only at Waterford and Dublin and that the coins must be clearly differentiated from those of England. He wisely avoided tampering with the government of Ireland, however. The Earl of Kildare was reappointed Deputy Lieutenant for a year, and further at the King's pleasure; all other officers were confirmed in their posts. Richard was careful to recognize also that other powerful peer, the Earl of Desmond. Desmond was requested to take an oath of allegiance to the King, and to renounce the wearing of Irish clothing. As an inducement, Richard sent him gowns, doublets, hose, and bonnets, and also the King's livery; a collar of gold worked in roses and suns with a white boar appended. One part of the instructions for Desmond casts an interesting light upon the past. The services of the Earl's father to Richard's father were, Richard assured him, warmly remembered. Further, the King and Desmond were bound by a common tie of sorrow, for those who had murdered the Earl's father (i.e., the Woodvilles) were the very ones who had encompassed the death of the Duke of

Clarence. If the Earl so desired, Richard promised to give him opportunity to prosecute the guilty parties at law. Brother George still cast a long shadow. 1 *

As for France, Richard's efforts this summer to redeem the dangerously ragged and uncertain situation his brother Edward had bequeathed him came to little. His ally Maximilian was busy fighting against rebellious subjects; the King of France was busy with Heaven. Richard's and Louis' minds touched once. Struggling to keep his grip on affairs even though he knew he was sinking to his end, King Louis replied to Richard's announcement of his assumption of the throne with a very informal, almost offhand, note; "Monsieur mon cousin, I have seen the letter that you sent me by your herald Blanc Sanglier and thank you for the news you've given me and if I can do you any service, I'll do it very willingly for I want to have your friendship. Adieu, Monsieur mon cousin."

This cool and cavalier communication the King of England answered from his castle of Leicester on August 18 in a letter which contains the only gleam of Richard's wit that has survived. The wit is grirn enough, but unmistakable. He lets Louis know that if France doesn't give a hang about the relations between the two countries, neither does England; he directly questions Louis' intentions; and he well-nigh parodies Louis' casual style. Louis need not think that Richard, though newly seated on the throne, is panting to be recognized by Louis! "Monsieur, mon cousin," he writes,

I have seen the letters you have sent me by Buckingham herald, whereby I understand that you want my friendship in good form and manner, which contents me well enough; for I have no intention of breaking such truces as have previously been concluded between the late King of most noble memory, my brother, and you for as long as they still have to ran [i.e^ till April 9, 1484]. Nevertheless, the merchants of this my kingdom of England, seeing the great provocations your subjects have given them in seizing ships and merchandise and other goods, are fearful of mentoring to go to Bordeaux and other places under your rule until they are assured by you that they can surely and safely carry on trade in all the places subject to your

sway, according to the rights established by the aforesaid truces. Therefore, in order that my subjects and merchants may not find themselves deceived as a result of this present ambiguous situation, I pray you that by my servant this bearer, one of the grooms of my stable [no more impressive envoy being called for!], you will let me know in ^ writing your full intentions, at the same time informing me if there is anything I can do for you in order that I may do it with good heart. And farewell to you, Monsieur mon cousin.

Richard had a clear understanding of the temper of Anglo-French relations, and of King Louis XL But Louis never saw this communication. He died at Plessis-Ies-Tours on August 30, leaving his heir, Charles VIII, and his realm to the regency of his shrewd daughter, Anne de Beaujeu. In the meantime, Richard had managed to send a small fleet to sea for the summer to operate against the French privateers. 15 *

Difficulties with France inevitably dictated a friendly approach to Francis, Duke of Brittany, who for almost two decades had been the wavering and timorous ally of Edward IV. On July 13 Richard appointed Dr. Thomas Hutton, "a man of pregnant wit," to negotiate with the Duke for a diet which would arrange for mutual redress of grievances—arising from piratical depredations on both sides—and re-establish the old league of friendship and intercourse of merchandise. Hutton was also instructed to "feel and understand the mind and disposition of the Duke anempst [in regard to] Sir Edward Woodville and his retinue, practicing by all means to him possible to ensearch and know if there be intended any enterprise out of land upon any part of this realm, certifying with all diligence all the news and disposition there from time to time." Richard made no mention of Henry Tudor, doubtless because he did not want Duke Francis to suppose that he regarded the Tudor as of any importance. He would soon learn, however, that Francis was not impressed by this omission. 16

Meanwhile, in his progress King Richard had at last entered Yorkshire. After pausing from August 20 to August 23 at Nottingham, he seems next day to have reached Pontefract, where he had summoned to meet him seventy knights and gentlemen of the North. His purpose was doubtless to inquire into the state

of local affairs and to read them the same lecture on administering justice which he had delivered to the lords in London. 17

At York the citizens had been busily preparing for a month to welcome their new King in a style which would show their love and uphold his honor. As soon as the news of his accession reached the citv, the Mayor and four Aldermen rode to Middle-ham to pay their homage to little Prince Edward and to present him with demain bread, a barrel of red and a barrel of white wine, six cygnets, six herons, and twenty-four rabbits. Not long after, they entered into exhaustive discussions concerning arrangements for the official welcome of their sovereign, sending for priests and men of the guilds who were expert at devising pageantry. Richard himself was no less eager that the chief men of his court be impressed by the reception he received at York. On August 23 John Kendall, Richard's secretary, penned an exuberant letter from Nottingham to the magistrates of the city. King Richard, he wrote, cherished them dearly. Though he himself knew they were preparing a welcome better than any he could devise, he could not resist expressing his hope that the King and Queen would be received with pageants, speeches, and arras and tapestry hanging in the streets—"for many southern lords and men of worship are with them and will greatly mark you receiving their Graces."