Ridiculous/Hilarious/Terrible/Cool (10 page)

Read Ridiculous/Hilarious/Terrible/Cool Online

Authors: Elisha Cooper

The Payton student body may be the best Ping-Pong-playing student body in America. From the start of the day until the last bell, the five Ping-Pong tables in the atrium are continually occupied.

There is one player who is better than everyone. He's a freshman, spectacled and Asian, the top of his jutting hair not much higher than the table. But he has all the shots, the swerving serves and funky grips. He even has a fan club of other small boys who circle the table and admire his every move. One of the kids in the club nods at the boy and whispers, “He's the

King

of Ping-Pong.”

King

of Ping-Pong.”

Anais Blake hurt her ankle. She was dancing in the studio over Thanksgiving break when she felt a sharp pain in her right foot. The pain spread down her arch and up her calf. After class she got a massage, but that didn't help. The following day she tried to dance but had to stop it hurt so bad. Now she's in the library, a place Anais rarely finds herself. A biology textbook lies unopened in front of her.

She's holding an ice pack to her foot. The foot is flushed, its veins pulsing. When Anais removes the ice pack she turns her ankle in circles, looking at it as if it's not part of her, as if it might start talking and reassure her that everything will be okay.

But it is impossible for Anais to separate from her body.

When Anais dances well, it's the most wonderful feeling in the world, the purest feeling, one where her body and soul are working together as one. It's almost as if she were a different person. When she is hurt, this feeling falls apart, and doubt creeps in. So this is more than an ankle sprain.

Anais says bodies do not lie. If her body is hurt, what does that say?

The more Anais looks at her ankle, the more she seems about to cry. The timing could not be worse. Her audition for the ballet conservatory at Indiana is on Friday.

Hanging over the security desk at the front door is a television monitor. The screen flips from weather reports (cold) to upcoming events (Choir Concert, 7:00), to this warning:

Cutting Classes?

Thinking of skipping class?

Don't do it!

You will be found!

Thinking of skipping class?

Don't do it!

You will be found!

Anthony Johnson Jr. ditched school last week. He and The Girl agreed to meet at the McDonald's, but they missed each other. There are a lot of McDonald's around Payton and they went to different McDonald's. The Girl didn't have a cell phone, so Anthony couldn't reach her, but on his way back to Payton there she was walking back to school too, so they took the "L” to Anthony's gray stone house on the West Side and hung out in his room, which was where his father caught him.

“I can't win! I ain't ever cut class without getting caught!” Anthony shouts up at the ceiling, slapping his table in the cafeteria and surprising the kids at the next one over. With that he gets up and heads to class (the class after the class he cut), shuffling down the hall in a slow pigeon-toed gait, disappearing into the student body.

DECEMBER

At this point in the year, the savvier students have found the dead spots that authority can't reach. The third floor near the windows to talk on cell phones. The carrels in the library farthest from the librarian. The elevator when security walks away from their desk.

The only truly dangerous spot remaining in the high school is the stairway on the second floor as it passes by the band room. That's where the band teacher stands between classes, staring at the students as they walk up, waiting to pounce on those who are late. The band teacher's patience is short, like his sideburns and his pants. Sometimes the traffic on the stairs bottles up and students are slowed down. Today a straggler is caught, an event heralded by some roaring from outside the band room. As the band teacher drives his prey downstairs to the security desk, he shouts, “When a teacher tells you to move,

you move

! Next time this happens,

I write you up

! And I don't need,

your mouth

!”

you move

! Next time this happens,

I write you up

! And I don't need,

your mouth

!”

It's Andy, the smaller half of Ben&Andy. He looks thoroughly annoyed. He's smart and good-looking, he will go to an excellent college. But right now, in the clutches of the band teacher, he's as helpless as a landed fish. That everyone else in the school is getting away with everything makes the indignity doubly wrong.

“I don't know what I'm doing yet,” Maya mutters as she walks toward the cafeteria. She's hugging a metal money box and a wheel of red tickets to her chest. She seems unsure how to proceed.

“I don't know what to do,” she mutters again, staring at the folding table outside the cafeteria doors. Two freshman boys with pimples walk by.

“Do you want to go to the play on Friday?” Maya calls to the backs of their heads. The boys turn and smile but keep walking. Another boy passes and doesn't acknowledge her. Maya shakes her head.

“Did you

see

that? He didn't even respond to me.

Argh,

that was so rude.” She sticks her tongue into her cheek, and sits down with a thump.

see

that? He didn't even respond to me.

Argh,

that was so rude.” She sticks her tongue into her cheek, and sits down with a thump.

“I'm terrible at this.”

Maya opens her money box and starts clucking her tongue. More boys walk past.

Then one friend approaches and buys a ticket. Maya gives a little clap and cries,

“Yay!”

A minute later, another friend and another ticket. Maya hops up and tracks down a boy across the hall. After ten minutes, and a few more sales, she's on a roll.

“Yay!”

A minute later, another friend and another ticket. Maya hops up and tracks down a boy across the hall. After ten minutes, and a few more sales, she's on a roll.

“Do you want to go to the play on Friday? I think you do!”

The last weeks have been stressful for Maya. Applications are taking up all her time. Getting her essay just right. Maya wrote hers about Bourbonnais, the town in Illinois her family moved from, the place that gave her the small-town look she hasn't entirely lost. She wrote about how everyone there is

French Canadian, how her house had woods and fields out back where she spent her childhood looking under rocks for worms, how she lived this bucolic life before moving to the big city. There's humor in her essay. But the process behind it has been intimidating.

“I've tried out for plays and gotten rejected,” Maya says, fingering one red ticket. “This is different. It's ultimate,

final

. It could be for life.”

final

. It could be for life.”

Maya is faced with this life-changing pressure, and yet her day-to-day worries have a way of intruding. For instance, she may be selling tickets for a play that won't go on. An assistant principal sat in on their rehearsal two days ago and had some issues. Maya's play is about a mother who abandons a newborn baby in a mall crèche. That wasn't the problem. The assistant principal, according to Maya, worried about the message being sent by having a character who slept around.

“They're ridiculous,” Maya says, nodding toward the administration offices where the play is being read by someone else in authority to make sure it is “safe.”

She bites her lip and frowns and says, not sounding fine, “It'll be fine.”

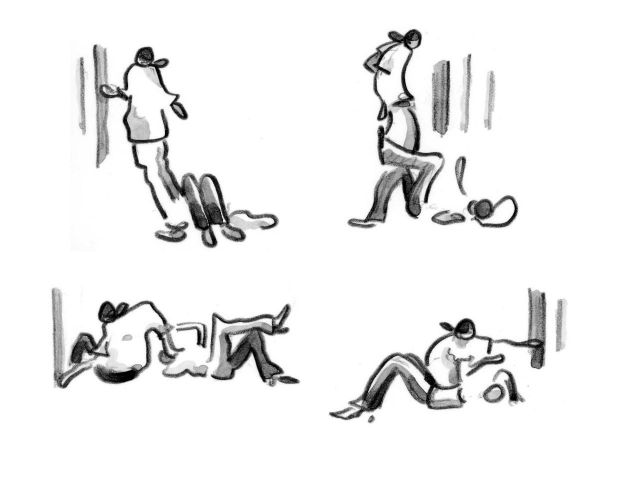

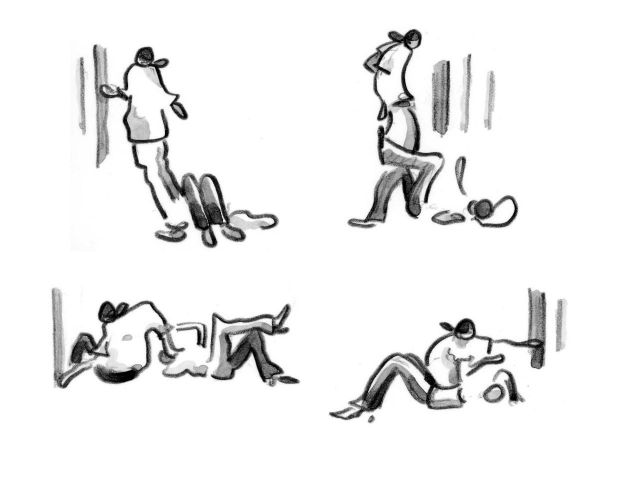

The atrium is a stage on which to perform for one's classmates. Every season needs a hit, and this fall it's a play starring the Homecoming King. The play has no words. It starts with the Homecoming King standing in front of his open locker. The Homecoming King's girlfriend lies on the floor beneath him, one leg crawling up the inside of the Homecoming King's thigh. She runs it up and down, hooking it behind the back of his leg, slowly dragging him to her. They sink downward. After twelve minutes they are lying together on the linoleum.

Other books

Khyber Run by Amber Green

Stepbrother Studs: Tristan by Selena Kitt

DoG by Unknown

The Nethergrim by Jobin, Matthew

Hope: A Tragedy by Shalom Auslander

Seers by Heather Frost

Night Seeker by Yasmine Galenorn

Dark And Dangerous by Sommer, Faye

Animalis by John Peter Jones