Ridiculous/Hilarious/Terrible/Cool (8 page)

Read Ridiculous/Hilarious/Terrible/Cool Online

Authors: Elisha Cooper

Phys ed is playing flag football on the field next to the high school. Students hug their elbows on the sidelines to stay warm. Everyone is hoping to play, or hoping they don't have to.

“We need a quarterback.

We need a quarterback,

” shouts one boy with spiky hair. A chubby boy takes a turn, throws an interception, and does not get another turn. At least he got to touch the ball. Girls don't. After half an hour, boys have thrown to boys on every single play. Girls don't get thrown to. They

stay on the sidelines, or run around the field in little ignored circles.

stay on the sidelines, or run around the field in little ignored circles.

We need a quarterback,

” shouts one boy with spiky hair. A chubby boy takes a turn, throws an interception, and does not get another turn. At least he got to touch the ball. Girls don't. After half an hour, boys have thrown to boys on every single play. Girls don't get thrown to. They

Then, maybe by mistake, a ball

is

thrown to a girl. She catches it, hops to the side to evade one onrushing boy, and then, with a gasp from the sidelinesâwho knew!âshe bursts past the other boys, her ponytail streaming behind her, and slides shyly into the end zone, not knowing what to do with the ball once she gets there.

is

thrown to a girl. She catches it, hops to the side to evade one onrushing boy, and then, with a gasp from the sidelinesâwho knew!âshe bursts past the other boys, her ponytail streaming behind her, and slides shyly into the end zone, not knowing what to do with the ball once she gets there.

Her team envelops her in a hug, almost lifting her up. It is a cold overcast morning, but as the girl is escorted to the sidelines, her teammates tousling her hair, the sun actually breaks through the gray.

NOVEMBER

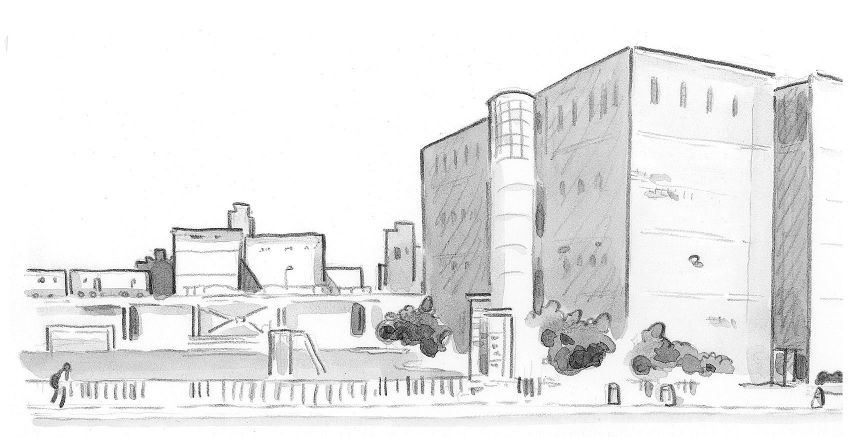

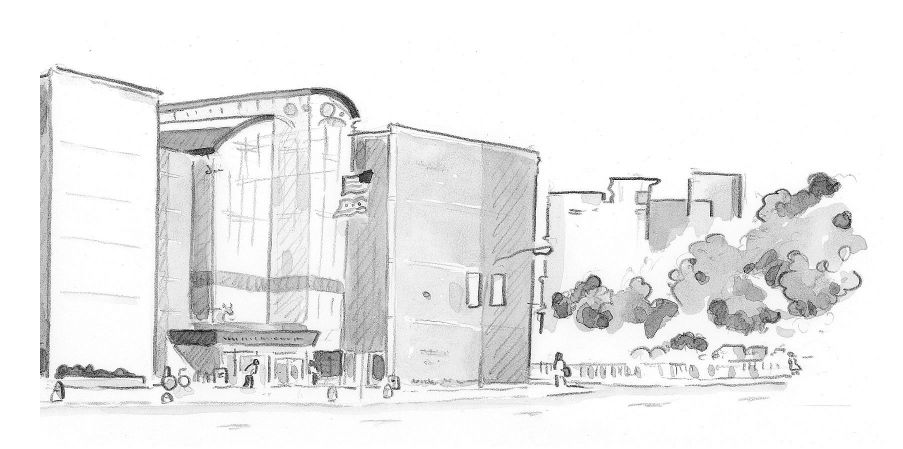

The trees in front of Payton have loosened their grip at the same time. Leaves are everywhere, skittering in whirlwinds, resting on the ground for a moment before lifting into the air again. The blustery weather outside seems to affect the atmosphere inside school. In Ms. Murphy's English class, things are sort of unmoored.

“Everyone look at me and create the illusion of focus!” begs Ms. Murphy in one of her carefully-worded-yet-ignored pleas. Her irony doesn't register. Attention is wandering. Not wandering, more like starring in a movie.

When Maya Boudreau daydreams about New York, she pictures herself starring in some cool independent

Lost in Translation

-type movie with Kevin Kline. Maya would play the Scarlett Johansson role, the smart ingénue. Kevin Kline would be Bill Murray. The role could be played by other actors of his generation whom she respects (Maya's daydreams are open to suggestion), but her first choice would be Kline. Wes Anderson, whose movies she loves, could direct.

Lost in Translation

-type movie with Kevin Kline. Maya would play the Scarlett Johansson role, the smart ingénue. Kevin Kline would be Bill Murray. The role could be played by other actors of his generation whom she respects (Maya's daydreams are open to suggestion), but her first choice would be Kline. Wes Anderson, whose movies she loves, could direct.

They would film on the streets of New York, in apartments and high-ceilinged lofts. The cast and crew would be professional, passionate. After the day's shoot, they would all go to an off-Broadway show, a late dinner, the night ending at a party in some Soho loft. In Maya's daydreams, more than a few lofts are involved.

As much as this is a daydream, Maya thinks it's plausible. It could happen, with or without Kevin Kline. It's a dream where each angle can be lovingly considered, a daydream she can lose herself in, a dream where a paper ripped from a notebook is the roar of the subway, the crack of knuckles are shoes walking down Broadway, the click of a mechanical pencil is the clink of a wine-glass, and the voice of the teacher is the director calling

Action

.

Action

.

When Ms. Murphy mentions that class may need to come in Saturday morning to watch a five-hour film version of

Hamlet,

attention is achieved

attention is achieved

like that

. It folds the set and packs the bags and gets on a plane back to Chicago, incredulous and breathless.

Hamlet,

like that

. It folds the set and packs the bags and gets on a plane back to Chicago, incredulous and breathless.

The entire class scurries back from their individual daydreams. There is complete utter focus on Ms. Murphy's next words. If a flipped pen could hang in the air, it would. She can

not

be serious. She

is

serious. Five minutes later, though, Ms. Murphy relents.

not

be serious. She

is

serious. Five minutes later, though, Ms. Murphy relents.

Everyone breathes again. Someone cracks her knuckles, someone rips a piece of paper, and the attention of the room whirls off into another dream, maybe out West, hiking through meadows in the shadow of snow-covered mountains, up into the clouds.

“If I get in, I'll probably do some sort of victory . . .” Daniel Patton's voice drifts off and he crosses his fingers. Daniel crosses his fingers often, especially when talking about applying to Harvard.

Daniel is sitting outside the guidance counselor's door again, his lanky frame tilting precipitously backward. If he tilted any farther he'd fall into the counselor's office. Daniel is wearing a gray Italian suit, a blue French tie. He's dressed up for a meeting down at city hall later today. He's not only the president of the Payton senior class, but also the mayor of Chicago in a YMCA youth council program that meets in the city council chambers.

Next week, on the day Daniel finds out whether or not he got in early admission to Harvard, he will be dressed up too.

School, a student council meeting, a meeting at city hall, then selling shoes at Nordstrom. Busy, busy, busy.

School, a student council meeting, a meeting at city hall, then selling shoes at Nordstrom. Busy, busy, busy.

The librarian walks past, waves, and says, “Hi, honey!”

He smiles up at her.

Daniel is waiting to fill his guidance counselor in on recent developments, check if there are any extra ways he can make himself appear to be a better candidate for Harvard. He finds the process nerve-racking. It's been testing his normally cool demeanor.

The door opens and the guidance counselor pokes his head out of his office.

“Are you retaking that test?”

“Yes. I'm studying for it.”

“No, you're not,” says the counselor. They both laugh. Daniel is the type of student that teachers want to take under their arms, that teachers hope will succeed. There are some concerns about Daniel's scores, however. His ACT score is good but not great. He's not getting straight A's, though he is taking difficult AP courses. He has more B's than A's.

But Daniel has all the incalculables. The extra-curriculars, the committees, the meetings, the recommendations, the respect of teachers and classmates. The

bearing

. The ability to convey that he is unfailingly eager and polite. Listening, conferencing, networking.

bearing

. The ability to convey that he is unfailingly eager and polite. Listening, conferencing, networking.

And all this takes effort.

Sometimes the effort leaves him with less time to study, to crack books as hard as he knows he should.

At the corner of Cermak and Throop on Chicago's South Side, in the shadow of a factory pumping steam into the night sky, is a cavernous brick warehouse indistinguishable from the other warehouses around it except for what is being manufactured inside: soccer players.

Chitown Fútbol

. Tuesday night and the place is thumping. On two turf fields, teams of girls in bright uniforms sprint after each other and kick balls off the walls. The warehouse echoes. Parents shout from the stands. In the middle of all this commotion, letting it spin around her, is Emily Harris.

. Tuesday night and the place is thumping. On two turf fields, teams of girls in bright uniforms sprint after each other and kick balls off the walls. The warehouse echoes. Parents shout from the stands. In the middle of all this commotion, letting it spin around her, is Emily Harris.

She does not run. She shuffles. With her elbows out, she looks like a cocky duck. Her shuffle actually makes her look like she's moving slower than the other players. But she has the sixth sense of knowing where the ball will be two passes before

it gets there, then shuffles to that spot before everyone else.

it gets there, then shuffles to that spot before everyone else.

As Emily settles the ball she does so gently, glancing up to see if her teammates are in the correct position. Emily is constantly thinking. Then two defenders rush her and she effortlessly slides the ball to one side, letting them charge past her as if they were bulls, before bending a perfect pass to an unmarked teammate for an open shot.

Gol

.

Gol

.

At halftime, Emily's team is ahead 8-0. Emily spends the second half distributing the ball to her teammates, shouting directions as if the other team were not there. The other team finds this particularly frustrating. They may as well be cones.

Other books

Stone Rain by Linwood Barclay

People in Season by Simon Fay

Moonlight Menage by Stephanie Julian

Nice Day to Die by Cameron Jace

All Gone by Stephen Dixon

Enchanted by Patti Berg

Jumping at Shadows by R.G. Green

Deathlist by Chris Ryan

Isaac Asimov by Fantastic Voyage

An Illustrated Outline of Buddhism: The Essentials of Buddhist Spirituality by William Stoddart, Joseph A. Fitzgerald