Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey (15 page)

Read Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey Online

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Philosophy, #TRV025000

To Photograph Every Mile

A

COUPLE OF MONTHS BEFORE

setting out to travel the Ouachita Valley, I had an electrician rewire a storage space I was converting into a small exercise room. I explained to the man, only a few years younger than I, old folks don’t need storage — they need muscle. The remark found resonance in him and considerably slowed the job, since he apparently wasn’t able to talk while simultaneously holding a tool or length of conduit. He put down his screwdriver to exposit more clearly his means of teaching his grandson rudiments of basketball to help the boy make his school team.

“I never played down to him. He had to match me, but it didn’t take long before he could outrun me, outjump me. That young body! Hell, he could get it to piss over the hood of a pickup.” He stopped. “Excuse my phraseology, but you know what I’m saying.”

He took a length of conduit, measured it, and put it down once more. “Oh, man! To be seventeen again!” (Conduit up, conduit down.) “He could outdo me in every way but one, and I had that advantage only because he couldn’t see it, no matter how I tried to explain it.” (Screw-driver in hand, screwdriver back into tool belt.) “Time!” he said, referring to what he was using too much of for my project. “The boy doesn’t know what to do with time except to burn it. That’s my one advantage. If he isn’t fiddling with an electronic game, he spends his time dreaming impossible things — climbing Mount Everest or dating some starlet of the hour.”

Having forgotten the conduit measurement, he remeasured. “I tell him, ‘Okay, you can outrun me, but what good is it if you’re not running to some productive place?’” (Here, a piece of conduit actually got attached to the wall.) “I tell him he’s like a trash collector, except he goes around just collecting days so he can haul them off to dump them.” (Junction box screwed to the wall.) “Time’s his enemy because he’s got too much of it, and it’s my enemy because I’m running out of it.” I could see why. (Next length of conduit measured and set down.) “Old Mother Nature’s a smart-ass, you know. When you finally learn how to use time, you can’t even piss over a hubcap.” (Conduit remeasured.) “Excuse my phraseology, but you know what I’m saying.”

The electrician’s ramble was to come back to me across the Ouachita in West Monroe at Gabbeaux’s Bayles Landing Restaurant, a riverside place, once a small fish market where

warp

and

lean

would be among the accurate words to describe it. Q and I were there to have lunch with a man, Glenn Gore, whose work she had learned of a month before I met the electrician. At Gabbeaux’s, beyond its interior of angles skewed enough to serve as a film set for a surrealist dream sequence, we took a table on a patio of generally true plumb lines.

Across the Ouachita rose several multistorey buildings in downtown Monroe where stood the large courthouse at the site of the 1790 Fort Miro, the Spanish outpost that received Dunbar and Hunter and rented them a boat better suited to the ascent of the river than the clumsy vessel they’d struggled to drag that far upstream. Fifteen years after the Forgotten Expedition passed through, the steamboat

James Monroe

reached the garrison. The settlers, hoping to encourage further custom, toyed with the name of Fort Miro as if playing with alphabet blocks and managed to erase the Hispanic lineage by commemorating both the economic promise of the first steamboat bravely ascending the Ouachita

and

the current President who, as a plenipotentiary, was a signer of the documents conveying title to the Louisiana Territory to the United States. Miro became Monroe, and with the change, the citizens turned on its head the more common practice of naming ships after cities. Later residents have fuzzed over the Spanish founding even further by pronouncing the name of the old fort to rhyme with

high flow,

a parallel not frivolous given the rise the river can effect there.

Few courthouses so boldly face a watercourse as does that of Ouachita Parish, the third building on the location, a neoclassic edifice of white stone and Ionic columns, one that might have been lifted from Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington. The federal government, in a sense, helped clear the grounds of an earlier and lesser building by authorizing Admiral David Porter’s ironclad gunboats to cannonade the town in 1863. Nothing of Fort Miro or of a couple of previous courthouses still stands, and vanished too are the early-twentieth-century houseboats where lived mussel-shell gatherers who once supplied button makers. And also gone with the winds of changing technology is the carbon-black industry that manufactured, among other things, pigment for ink out of natural gas from nearby wells. Now the gas is sent elsewhere for heat and power generation. Some street names in the old African-American section of shotgun houses proved equally evanescent: Adam and Eve Alley, Concrete Quarters, Owl Lane (all changed to honor civil rights workers), but Congo Street remained, as did, in a white section, Polly Anna.

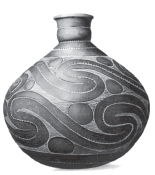

Still in existence too, although no longer on the banks of the Ouachita, were creations of the first inhabitants, ceramics of wondrous beauty found in an oat field on the former Glendora Plantation, later demolished for an industrial site. Thirteen miles north of what would become the Mohawk Tavern, archaeologist Clarence Moore in 1909 turned up pots, bowls, jugs, bottles, and receptacles with sculpted figures, all made from local clay incised and painted with remarkable scroll patterns. One cannot really apprehend the Ouachita Valley without laying eyes on the ceramic art of those people. Here is a pre-Columbian vessel, its hues buff and brick red, that in itself may convey a deeper sense of the river valley.

On the morning we sat beside the Ouachita, it was making an easy descent, its passage as insouciant and heedless as an adolescent’s hours. Had the old river a mind, it would surely see us all — William Dunbar, the mussel-shell collectors, even the Glendora potters — not so much as sharing a continuum as belonging to the same moment. Could I only develop a like notion of time, maybe a few more things would make some sense.

We read the menu: five-pound bucket of boiled crawfish, price on request (Q: “You aren’t, are you?”); spicy boudin balls (waitresses tired of that old wisecrack); fried crawfish tails (and that one too); catfish chips (not to be confused with those of the buffalo); an assortment of gumbos, étoufées, bisques, jambalayas; and, of course, red beans and rice. The menu in mind, Q said, “Does this mean we’ll be staying an extra week?”

Glenn Gore was a man of modest height, sixty-four years old, dark hair with a little seepage of gray at the temples. He carried some Choctaw blood, signs of which showed if one knew what to look for (not coloring or cheekbones of popular perception; earlobes are a far better indicator). He was born about thirty miles downriver, near Columbia, but he had been in Monroe since his second year. For almost a third of a century, he’d been living on the banks of the Ouachita where he started fishing and hunting at an age when he was too small to see over the steering wheel and too big to stay inside the fence. Around 1910, his grandfather sold vegetables to the steamboat crews when they stopped to lock through the old dam below Monroe. Because the city takes its municipal water from the Ouachita basin, you could say that the river flowed through his heart as well as his brain. Take away the Ouachita, and you’d not have Glenn Gore, at least not one anybody thereabouts would recognize. I should mention here that he preferred listening and modest statement of fact to the free-flowing palaveration so happily abundant in the South.

An engineer trained not formally but in industry, he identified himself as a photographer, although his initial work as an artist was with scratchboard, a nineteenth-century technique of engraving a reversed and negative image on a coated surface. It was a scratchboard scene that led him to discover a link between his art and the river, which is also the link between his being alive and the reason

for

his being alive. In 1989, needing backgrounds to use in his wildlife engravings, he took a camera and went down to the Ouachita to shoot not rabbits but scenery. Then he began trying to find published images of and information about the river but came up with only bits and pieces so limited and scattered that, even if assembled into one volume, the book would still be woefully incomplete.

Gore began working to photograph

every mile

of the Ouachita from head to foot, Rich Mountain to Jonesville, most of the lower miles accessible only by traveling the river itself in a sixteen-foot johnboat; but in the Ouachita foothills and up into the mountains, it was largely legwork. His first search was fifteen years ago, some six-thousand photographs of the Ouachita ago, 120 hours of video of the river ago, dozens of concerned messages to legislators ago. His unpresumption led him to say only, “Maybe I got carried away.” I said, Rivers could do that.

The sense of riverness he had discovered within himself seemed to exist in few others, so he decided to try to change the disregard, neglect, and abuse of the major natural reason his neighbors lived where they lived, the very source of almost two-thirds of their bodies.

Of the six-hundred miles of river, he had, after fifteen years, multiple photographs of something less than half the Ouachita. It was a project other people could have undertaken, but no one had, and it seemed unlikely anybody would, at least not before accelerating changes —

deteriorations,

to use his word — obliterated much beauty and history along the river. Already it was too late to bring back things like the stunning aboriginal pyramid — and the knowledge its artifacts could have led to — bulldozed in 1932 for road fill at the mouth of the Ouachita. Too late to save the Glendora site, once yielding several hundred peerless ceramic vessels. No longer was there opportunity to capture images of the river before virtually all of it beyond the mountains was forced into pools and reservoirs. Yet he believed much still remained that William Dunbar and George Hunter would recognize, views the Ouachita people themselves would know.

Seven years after his discovery of the skimpiness of documentation of the river, he organized the Ouachita River Foundation, essentially a one-man venture assisted only by his wife, son, and a board of directors. He feared open membership and acceptance of grants might impair advocacy. Nevertheless, his work garnered enough respect to draw a few small contributions from businesses and individuals. He had made five videos for showing to all who asked, and every year he published a full-color calendar, each month illustrated by a photograph of the Ouachita. To many of the dates, he added relevant river history

(March 3: During the Civil War five gunboats shelled the town of Jonesville, La., from the Ouachita River, 1863),

national history

(June 2: American Indians became U.S. citizens by Act of Congress, 1924),

or American lore

(March 18: Electric razor first marketed, 1931).

Sale of the calendars underwrote his documentation of the river.

His efforts to awaken and inform have inspired others. Reca (pronounced “Reesa”) Bamburg Jones, a woman standing only three inches above five feet, once sat down and, so to speak, dug in her heels in front of a bulldozer sent by a timber company to clear out a hunk of riverine woods protecting a five-thousand-year-old archaeological site. Mrs. Jones managed to redirect the machine and prevent a total deforestation. She was later able to enlist archaeologist Joe Saunders to establish the remarkable age of the mound complex, today completely hidden in the woods. Because of their efforts, the State of Louisiana purchased half the Watson Brake tract so that it might one day become an archaeological park. The heel of a hundred-pound woman exerts more pressure per square centimeter than an equivalent area under the steel track of a bulldozer: a law of mechanics — and sometimes of society.

I suggested to Glenn a historic soft-drink bottling plant, now shut down and yielding nothing to the community, could make a good Ouachita River Center. Precedent was there for the change: a World War II B-24 bomber training field near town had been turned into a museum. Gore thought it unlikely the city council would see a living river as worthy of commemoration and interpretation as is aerial warfare. That same bureaucracy paid scarce attention to the other side of the Ouachita and the success West Monroe had achieved in transforming itself and its little Main Street into a reawakened town of history and new businesses serving a new century. Leaders on the east side seemed to have no interest in creating a downtown where Auntie’s Antiques could coexist next to Titanic Telephone, each contributing something productively different.

What, I asked, was the attitude of the city newspaper toward the motto of the Ouachita River Foundation, “Preservation of Beauty and History”? Gore said, “The

News-Star

isn’t locally owned anymore, but in the past, it showed interest mostly when the river was rising.” (Q: “I think you might be causing a rise.”) “Maybe,” he said. “Sometimes I think I see good changes.”

What about the black community for whom, historically, the river was so important? “Getting them involved is a struggle too,” Gore said. “I know they have other issues of real importance, so how much can a man ask?” He was watching the water slip by as he spoke, and then, without taking his eyes off the Ouachita, he said, “It’s a struggle all the way, all the time, but I believe what we do matters. If we do it in the right spirit, we can shape the future for the good of the river and ourselves. They aren’t separate.”