Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (136 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

Figure 12.18

Longitudinal section of the stomach.

The stomach is divided into three regions: the fundus, the body and the pylorus. At the distal end of the pylorus is the pyloric sphincter, guarding the opening between the stomach and the duodenum. When the stomach is inactive the pyloric sphincter is relaxed and open, and when the stomach contains food the sphincter is closed.

Walls of the stomach

The four layers of tissue that comprise the basic structure of the alimentary canal (

Fig. 12.2

) are found in the stomach but with some modifications.

Muscle layer

(

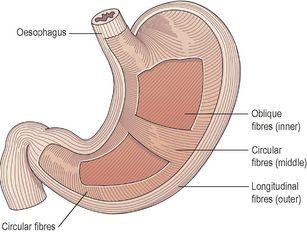

Fig. 12.19

). This consists of three layers of smooth muscle fibres:

•

an outer layer of longitudinal fibres

•

a middle layer of circular fibres

•

an inner layer of oblique fibres.

Figure 12.19

The muscle fibres of the stomach wall.

Sections have been removed to show the three layers.

In this respect, the stomach is different from other regions of the alimentary tract as it has three layers of muscle instead of two.

This arrangement allows for the churning motion characteristic of gastric activity, as well as peristaltic movement. Circular muscle is strongest in the pylorus and pyloric sphincter.

Mucosa

When the stomach is empty the mucous membrane lining is thrown into longitudinal folds or

rugae

, and when full the rugae are ‘ironed out’ and the surface has a smooth, velvety appearance. Numerous

gastric glands

are situated below the surface in the mucous membrane and open on to it (

Fig. 12.20

). They consist of specialised cells that secrete

gastric juice

into the stomach.

Figure 12.20

Coloured scanning electron micrograph of the mucous membrane lining the stomach showing the entrance to a gastric gland.

Blood supply

Arterial supply to the stomach is by the left gastric artery, a branch of the coeliac artery, the right gastric artery and the gastroepiploic arteries. Venous drainage is through veins of corresponding names into the portal vein.

Figures 5.44

and

5.46

(pp. 101 and 103

) show these vessels.

Gastric juice and functions of the stomach

Stomach size varies with the volume of food it contains, which may be 1.5 litres or more in an adult. When a meal has been eaten the food accumulates in the stomach in layers, the last part of the meal remaining in the fundus for some time. Mixing with the gastric juice takes place gradually and it may be some time before the food is sufficiently acidified to stop the action of salivary amylase.

The activity of gastric muscle consists of a churning movement that breaks down the bolus and mixes it with gastric juice, and peristaltic waves that propel the stomach contents towards the pylorus. When the stomach is active the pyloric sphincter closes. Strong peristaltic contraction of the pylorus forces

chyme

, gastric contents after they are sufficiently liquefied, through the pyloric sphincter into the duodenum in small spurts. Parasympathetic stimulation increases the motility of the stomach and secretion of gastric juice; sympathetic stimulation has the opposite effect.

Gastric juice

About 2 litres of gastric juice are secreted daily by specialised secretory glands in the mucosa (

Fig. 12.21

). It consists of:

•

mucus secreted by mucous neck cells in the glands and surface mucous cells on the stomach surface

•

inactive enzyme precursors: pepsinogens secreted by

chief cells

in the glands.

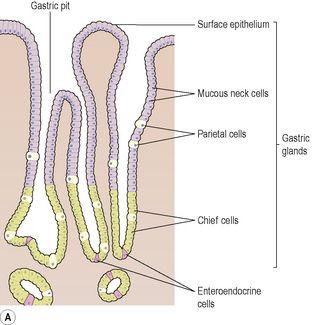

Figure 12.21

Structure of the gastric mucosa showing gastric glands. A.

Diagram.

B.

Stained section of the pyloric region of the stomach (magnified x 150).

Functions of gastric juice

•

Water

further liquefies the food swallowed.

•

Hydrochloric acid

:

–

acidifies the food and stops the action of salivary amylase

–

kills ingested microbes

–

provides the acid environment needed for effective digestion by pepsins.

•

Pepsinogens

are activated to

pepsins

by hydrochloric acid and by pepsins already present in the stomach. These enzymes begin the digestion of proteins, breaking them into smaller molecules. Pepsins act most effectively at a very low pH, between 1.5 and 3.5.

•

Intrinsic factor

(a protein) is necessary for the absorption of vitamin B

12

from the ileum.

•

Mucus

prevents mechanical injury to the stomach wall by lubricating the contents. It prevents chemical injury by acting as a barrier between the stomach wall and the corrosive gastric juice. Hydrochloric acid is present in potentially damaging concentrations and pepsins would digest the gastric tissues.

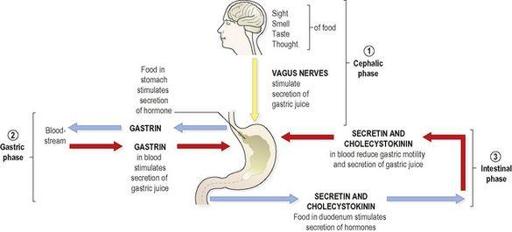

Secretion of gastric juice

There is always a small quantity of gastric juice present in the stomach, even when it contains no food. This is known as fasting juice. Secretion reaches its maximum level about 1 hour after a meal then declines to the fasting level after about 4 hours.

There are three phases of secretion of gastric juice (

Fig. 12.22

).