Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (164 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

Renal failure

Acute renal failure

There is a sudden and severe reduction in the glomerular filtration rate and kidney function that is often reversible over days or weeks if treated. There is oliguria or anuria accompanied by metabolic acidosis due to retention of H

+

; electrolyte imbalance; accumulation of other mainly nitrogenous waste products; and, if not associated with severe fluid loss, retention of water, i.e. substances normally excreted in urine are retained in the body. This occurs as a complication of a variety of conditions not necessarily associated with the kidneys. The causes of acute renal failure are classified as:

•

prerenal

: the result of reduced renal blood flow, especially as a consequence of, e.g., severe and prolonged shock

•

renal

: occurs due to damage to the kidney itself due to, e.g., acute tubular necrosis, glomerulonephritis

•

postrenal

: arises from obstruction to the outflow of urine, e.g. disease of the prostate gland, tumour of the bladder, uterus or cervix, large calculus (stone) in the renal pelvis.

Acute tubular necrosis (ATN)

This is the most common cause of acute renal failure. There is severe damage to the tubular epithelial cells caused by ischaemia or, less often, by nephrotoxic substances (

Box 13.2

).

Box 13.2

Some causes of ATN

Ischaemia

– severe shock, dehydration, haemorrhage, trauma; extensive burns; myocardial infarction; prolonged and complex surgery, especially in older people

Drugs

– e.g. aminoglycoside antibiotics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), ACE inhibitors, lithium compounds, paracetamol overdose

Haemoglobinaemia

– accumulation of haemoglobin, released by haemolysis of red blood cells, e.g. incompatible blood transfusion, malaria

Myoglobinaemia

– accumulation of myoglobin released from damaged muscle raises blood levels, e.g. following crush injury (

p. 425

).

Oliguria

,

severe oliguria

(less than 100 ml of urine per day in adults) or

anuria

(see

Table 13.1

) may last for a few weeks, followed by profound diuresis. There is reduced glomerular filtration and selective reabsorption and secretion by the tubules, leading to:

•

heart failure due to fluid overload

•

generalised and pulmonary oedema

•

accumulation of urea and other metabolic waste products

•

electrolyte imbalance which may be exacerbated by the retention of potassium (hyperkalaemia) released from damaged cells anywhere in the body

•

acidosis due to hydrogen ion retention.

Profound diuresis (the diuretic phase) occurs during the healing process when the epithelial cells of the tubules have regenerated but are still incapable of selective reabsorption and secretion. Diuresis may lead to acute dehydration, complicating the existing high plasma urea, acidosis and electrolyte imbalance. If the patient survives the initial acute phase, a considerable degree of renal function is usually restored over several weeks (the recovery phase).

Chronic renal failure

This occurs when the renal reserve is lost and there is irreversible damage to about 75% of nephrons. Onset is usually slow and asymptomatic, progressing over several years. The main causes are diabetes mellitus, glomerulonephritis and hypertension.

The effects on glomerular filtration rate (GFR), selective reabsorption and tubular secretion are significant. GFR and filtrate volumes are greatly reduced, and reabsorption of water is seriously impaired. This results in production of up to 10 litres of urine per day (

Table 13.3

). Reduced glomerular filtration leads to accumulation of waste substances in the blood, notably urea and creatinine. When renal failure becomes evident, blood urea levels are raised and this is referred to as

uraemia

. Some of the signs and symptoms that may accompany this condition include nausea, vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding, anaemia and pruritus (itching). Others are explained below.

Table 13.3

Polyuria in chronic renal failure

| | Normal kidney | End-stage kidney |

|---|---|---|

| GFR | 125 ml/min or 180 l/day | 10 ml/min or 14 l/day |

| Reabsorption of water | >99% | Approx. 30% |

| Urine output | <1 ml/min or 1.5 l/day | Approx. 7 ml/min or 10 l/day |

Polyuria

Large volumes of dilute urine (with a low specific gravity) are passed, because water reabsorption is impaired.

Nocturia

is a common presenting symptom.

Acidosis

As the kidney buffer system that normally controls the pH of body fluids fails, hydrogen ions accumulate.

Electrolyte imbalance

This is also the result of impaired tubular reabsorption and secretion.

Anaemia

Deficiency of erythropoietin (

p. 60

) occurs after a few months, causing anaemia that is usually exacerbated by haemodialysis which damages red blood cells. If untreated, anaemia results in fatigue, and may also lead to dyspnoea and cardiac failure. Tiredness and breathlessness are sometimes the initial symptoms of chronic renal failure.

Hypertension

This is often a consequence, if not a cause, of renal failure.

End-stage renal failure

When death is likely without renal replacement therapy, such as haemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis or a kidney transplant, the condition is referred to as

end-stage renal failure

. The excretory functions of the kidneys are lost, acid–base balance cannot be maintained and endocrine functions of the kidney are disrupted.

Towards the end of life anorexia, nausea and very deep (Kussmaul’s) respirations occur as uraemia progresses. In the final stages there may be hiccoughs, itching, vomiting, muscle twitching, seizures, drowsiness and coma.

Renal calculi

Calculi (stones) form in the kidneys and bladder when urinary constituents normally in solution are precipitated. The solutes involved are usually oxalates and phosphates. They are more common in males and after 30 years of age and the condition is often recurrent. Most originate in the collecting tubules or renal papillae. They then pass into the renal pelvis where they may increase in size. Some become too large to pass through the ureter and may obstruct the outflow of urine, causing kidney damage. Others pass to the bladder and are either excreted or increase in size and obstruct the urethra (

Fig. 13.25

). Sometimes stones originate in the bladder, usually in developing countries and often in children. Predisposing factors include:

•

Dehydration

. This leads to increased reabsorption of water from the tubules but does not change solute reabsorption, resulting in a reduced volume of highly concentrated filtrate in the collecting tubules.

•

pH of urine

. When the normally acid filtrate becomes alkaline, some substances may be precipitated, e.g. phosphates. This occurs when the kidney buffering system is impaired and in some infections.

•

Infection

. Necrotic material and pus provide foci upon which solutes in the filtrate may be deposited and the products of infection may alter the pH of the urine. Infection sometimes leads to alkaline urine (see above).

•

Metabolic conditions

. These include hyperparathyroidism and gout.

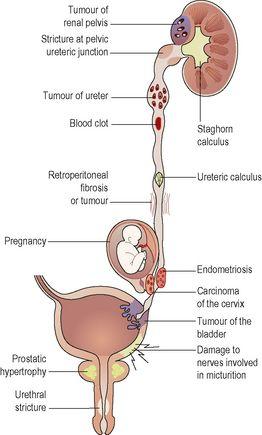

Figure 13.25

Summary of obstructions of the urinary tract.

Small calculi

These may pass through or become impacted in a ureter and damage the epithelium, leading to haematuria and after healing, fibrosis and stricture. In ureteric obstruction, usually unilateral, there is spasmodic contraction of the ureter, causing acute intermittent ischaemic pain (

renal colic

) as the smooth muscle of the ureter contracts over the stone in an attempt to move it. Stones reaching the bladder may be passed in urine or increase in size and eventually obstruct the urethra. Consequences include retention of urine and bilateral hydronephrosis (

p. 348

), infection proximal to the blockage, pyelonephritis and severe kidney damage.

Large calculi (staghorn calculus)

One large stone may form, usually over many years, filling the renal pelvis and the calyces (see

Fig. 13.25

). It causes stagnation of urine, predisposing to infection, hydronephrosis and occasionally kidney tumours. It may cause chronic renal failure.

Congenital abnormalities of the kidneys

Misplaced (ectopic) kidney

One or both kidneys may develop in abnormally low positions. Misplaced kidneys function normally if the blood vessels are long enough to provide an adequate blood supply but a kidney in the pelvic cavity may cause problems during pregnancy as the expanding uterus compresses renal blood vessels or the ureters. If the ureters become kinked there is increased risk of infection as there is a tendency for reflux and backflow to the kidney. There may also be difficulties during childbirth.

Polycystic disease

The

infantile form

is very rare and is usually fatal in early childhood.

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD)

This is inherited as an autosomal dominant condition (

p. 433

) that may become apparent any time between childhood and late adult life. Both kidneys are affected. Dilations (cysts) form at the junction of the distal convoluted tubules and collecting ducts. The cysts slowly enlarge and pressure causes ischaemia and destruction of nephrons. The disease is progressive and secondary hypertension is common; chronic renal failure affects about 50% of patients. Death may be due to chronic renal failure, cardiac failure or subarachnoid haemorrhage due to increased incidence of berry aneurysms of the circulus arteriosus. Cysts may also develop in the liver, spleen and pancreas but are not associated with dysfunction of these organs.

Tumours of the kidney

Benign tumours are relatively uncommon.

Malignant tumours

These are most common in the bladder or kidney.