Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (33 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

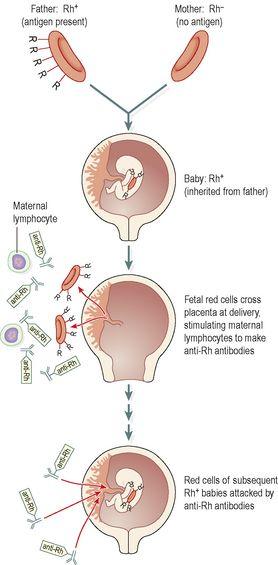

Figure 4.14

The immunity of haemolytic disease of the newborn.

The disease is much less common than it used to be, because it was discovered that if a Rh

−

mother is given an injection of anti-Rh antibodies within 72 hours of the delivery of a Rh

+

baby, her immune system does not make its own anti-Rh antibodies to the fetal red cells. Subsequent pregnancies are therefore not affected. The anti-Rh antibodies given to the mother bind to, and neutralise, any fetal red cells present in her circulation before her immune system becomes sensitised to them.

Acquired haemolytic anaemias

In this context, ‘acquired’ means haemolytic anaemia in which no familial or racial factors have been identified. There are several causes.

Chemical agents

These substances cause early or excessive haemolysis, e.g.:

•

some drugs, especially when taken long term in large doses, e.g. sulphonamides

•

chemicals encountered in the general or work environment, e.g. lead, arsenic compounds

•

toxins produced by microbes, e.g.

Streptococcus pyogenes, Clostridium perfringens

.

Autoimmunity

In this disease, individuals make antibodies to their own red cell antigens, causing haemolysis. It may be acute or chronic and primary or secondary to other diseases, e.g. carcinoma, viral infection or other autoimmune diseases.

Blood transfusion reactions

Individuals do not normally produce antibodies to their own red blood cell antigens; if they did, the antigens and antibodies would react, causing clumping and lysis of the erythrocytes (see

Fig. 4.7

). However, if individuals receive a transfusion of blood carrying antigens different from their own, their immune system will recognise them as foreign, make antibodies to them and destroy them (transfusion reaction). This adverse reaction between the blood of incompatible recipients and donors leads to haemolysis within the cardiovascular system. The breakdown products of haemolysis lodge in and block the filtering mechanism of the nephron, impairing kidney function. Other principal signs of a transfusion reaction include fever, chills, lumbar pain and shock.

Other causes of haemolytic anaemia

These include:

•

parasitic diseases, e.g. malaria

•

ionising radiation, e.g. X-rays, radioactive isotopes

•

destruction of blood trapped in tissues in, e.g., severe burns, crush injuries

•

physical damage to cells by, e.g., artificial heart valves, kidney dialysis machines.

Normocytic normochromic anaemia

In this type the cells are normal but the numbers are reduced, and the proportion of reticulocytes in the blood may be increased as the body tries to restore erythrocyte numbers to normal. This occurs:

•

in many chronic conditions, e.g. in chronic inflammation

•

following severe haemorrhage

•

in haemolytic disease.

Polycythaemia

This means an abnormally large number of erythrocytes in the blood. This increases blood viscosity, slows the rate of flow and increases the risk of intravascular clotting, ischaemia and infarction.

Relative increase in erythrocyte count

This occurs when the erythrocyte count is normal but the blood volume is reduced by fluid loss, e.g. excessive serum exudate from extensive burns.

True increase in erythrocyte count

Physiological

Prolonged hypoxia stimulates erythropoiesis and the number of cells released into the normal volume of blood is increased. This occurs naturally in people living at high altitudes where the oxygen tension in the air is low and the partial pressure of oxygen in the alveoli of the lungs is correspondingly low. Each cell carries less oxygen so more cells are needed to meet the body’s oxygen needs.

Pathological

The reason for this increase in circulating red cells, sometimes to twice the normal number, is not known. It may be secondary to other factors that cause hypoxia of the red bone marrow, e.g. cigarette smoking, pulmonary disease, bone marrow cancer.

Leukocyte disorders

Learning outcomes

After studying this section, you should be able to:

define the terms leukopenia and leukocytosis

review the physiological importance of abnormally increased and decreased leukocyte numbers in the blood

discuss the main forms of leukaemia, including the causes, signs and symptoms of the disease.

Leukopenia

In this condition, the total blood leukocyte count is less than 4 × 10

9

/l (4000/mm

3

).

Granulocytopenia (neutropenia)

This is a general term used to indicate an abnormal reduction in the numbers of circulating granulocytes (polymorphonuclear leukocytes), commonly called neutropenia because 40 to 75% of granulocytes are neutrophils. A reduction in the number of circulating granulocytes occurs when production does not keep pace with the normal removal of cells or when the life span of the cells is reduced. Extreme shortage or the absence of granulocytes is called

agranulocytosis

. A temporary reduction occurs in response to inflammation but the numbers are usually quickly restored. Inadequate granulopoiesis may be caused by:

•

drugs, e.g. cytotoxic drugs, phenothiazines, some sulphonamides and antibiotics

•

irradiation damage to granulocyte precursors in the bone marrow by, e.g., X-rays, radioactive isotopes

•

diseases of red bone marrow, e.g. leukaemias, some anaemias

•

severe microbial infections.

In conditions where the spleen is enlarged, excessive numbers of granulocytes are trapped, reducing the number in circulation. Neutropenia predisposes to severe infections that can lead to septicaemia and death. Septicaemia is the presence of significant numbers of active pathogens in the blood. The pathogens are commonly

commensals

, i.e. microbes that are normally present in the body but do not usually cause infection, such as those in the bowel.

Leukocytosis

An increase in the number of circulating leukocytes occurs as a normal protective reaction in a variety of pathological conditions, especially in response to infections. When the infection subsides the leukocyte count returns to normal.

Pathological leukocytosis exists when a blood leukocyte count of more than 11 × 10

9

/l (11 000/mm

3

) is sustained and is not consistent with the normal protective function. One or more of the different types of cell is involved.

Leukaemia

Leukaemia is a malignant proliferation of white blood cell precursors by the bone marrow. It results in the uncontrolled increase in the production of leukocytes and/or their precursors. As the tumour cells enter the blood the total leukocyte count is usually raised but in some cases it may be normal or even low. The proliferation of immature leukaemic blast cells crowds out other blood cells formed in bone marrow, causing anaemia, thrombocytopenia and leukopenia (pancytopenia). Because the leukocytes are immature when released, immunity is reduced and the risk of infection high.

Causes of leukaemia

Some causes of leukaemia are known but many cases cannot be accounted for. Some people may have a genetic predisposition that is triggered by environmental factors, including viral infection. Other known causes include:

Ionising radiation

Radiation such as that produced by X-rays and radioactive isotopes causes malignant changes in the precursors of white blood cells. The DNA of the cells may be damaged and some cells die while others reproduce at an abnormally rapid rate. Leukaemia may develop at any time after irradiation, even 20 or more years later.