Russell - A Very Short Indroduction (13 page)

In politics Russell was all his life a radical and, in the small ‘l’ sense, a liberal. After the First World War he became a member of the Labour Party and stood as its candidate in two elections. He tore up his membership card in the 1960s in disgust at Harold Wilson’s support for American war-making in Vietnam. But he was never a socialist in the old-fashioned sense, having been unpersuaded by Marxism when he studied it in Germany in the 1890s for his first book,

German Social Democracy

(‘social democracy’ then denoted Marxism). He was temperamentally opposed to the centralizing tendency of socialism as then understood – which was practically the only aspect of socialism (or ‘socialism’) ever put fully into practice in the Soviet world – and was accordingly much more attracted by Guild Socialism, a highly decentralized form of cooperative ownership and control in which

8.

8.

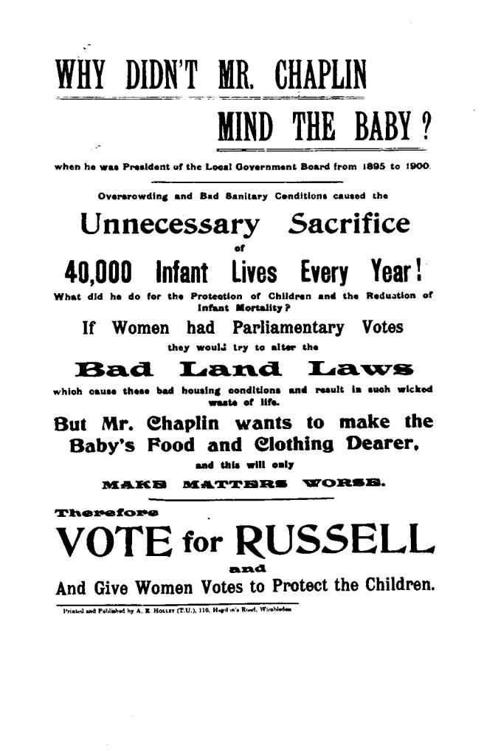

Russell stood as a parliamentary candidate on behalf of female suffrage at the Wimbledon by-election of 1907.

people govern themselves in circumstances that, in the ideal, integrate their social, recreational, and working lives.

Russell was at his best when criticizing contemporary moral and political conditions. The positive alternatives he suggested typically look unpersuasive, tending to be either utopian or, at very least – given the circumstances in which he offered them – impracticable to a degree. But as critic, scourge, and gadfly he is in the league of Socrates and Voltaire.

No one needs an excuse or a licence to contribute to debate on the great questions of society – the questions of politics, morals, and education. It is, arguably, a civic duty to be an informed participant. Russell’s activities in these respects therefore need no justification. But there is a good reason why his contributions have a certain authority. It is that he was better equipped than many for the task. This is not because he was an inheritor of a grand Whig tradition of involvement in public affairs, although no doubt this prompted both his interest in them and his sense of obligation to take part. Rather it was because his interest and sense of obligation were supported by four priceless assets: an extraordinary intelligence, a lucid eloquence, a broad knowledge of history, and complete fearlessness in the face of opposition. This made him a formidable debater. It was only at the end of his life, when others around him were speaking and writing in his name, that he sounded shrill and ill-judging.

Some of his ideas, such as belief in world government, have so far found little support. Others helped transform the social landscape of the Western world, as, for example, in attitudes to marriage and sexual morality. In other spheres again – not least in connection with religion – Russell liberated many minds, but he would not be surprised, given his understanding of human nature, to find that superstition flourishes even more now than in his day, and that dogma – ‘faith is what I die for, dogma is what I kill for’ – is back with a vengeance.

Theoretical ethics

In his very earliest thinking about ethics Russell held the romantic Hegelian view that the universe is good in itself and a fit object for ‘intellectual love’. His acceptance of this view was inspired by McTaggart, but it did not retain its hold on him for long. His first serious treatment of ethical questions, set out in his paper ‘The Elements of Ethics’ and published in 1910, shows Russell following the teaching of G. E. Moore’s

Principia Ethica

, in which Moore argues that goodness is an indefinable, unanalysable, but objective property of things, actions, and people, which we perceive by an act of direct moral intuition. Moore held a version of utilitarianism, which can be summarized as the view that the right thing to do in any given case is whatever will result in promoting the greatest balance of good over ill in that case. Moore’s views were influential among members of the Bloomsbury set, not least in promoting the attractive idea that friendship and the enjoyment of beauty are the highest ethical goods. (Unkind critics claimed that the Bloomsburies liked this view because they could economize – so to speak – by having beautiful friends.)

Difficulties immediately suggest themselves in connection with the utilitarian view. One is that we cannot know fully what the consequences will be of acting one way rather than another, and therefore we might inadvertently promote bad consequences as a result of muddled thinking or mistaken intuitions. In his version of Moore’s view Russell acknowledges this, but argues that we have acted rightly when we are satisfied that we have thought matters through carefully, and done our best on the available information. The claim that goodness is objective, however, is another matter, and Russell could not be content with it for long, for although it might, strictly speaking, be irrefutable, neither can it be proved correct, most significantly in the face of someone who flatly disagrees with another’s intuition that goodness is present in such-and-such an act or situation.

This difficulty led Russell to adopt the view, expressed in

An Outline of Philosophy

(1927), that moral judgements are not objective – that is, are not true or false – but are instead disguised imperatives, optatives, or statements of attitude. An imperative is a command, such as ‘do not tell lies’, an optative is a choice or wish – as when one opts for one thing rather than another – in the ethical case expressible by ‘would that no one told untruths’; and ‘I disapprove of lying’ is a report of its utterer’s attitude to lying. Imperatives and optatives obviously lack truth-value. Although matters are otherwise with reports of attitudes, this is only because they are descriptions of the relevant psychological fact about their possessors; nothing true or false is being said about the moral value of lying, only about what the speaker thinks of lying.

This position might, to contrast it with Moore’s objectivism, be called ‘subjectivism’. It suffers from equally grave problems, not the least of which is that it is straightforwardly implausible. Consider, say, the Holocaust. It is intolerable to think that one’s ground for judging that the Holocaust is evil is merely that one disapproves of it. Russell felt this difficulty acutely, and therefore in his final and fullest discussion of these questions (

HSEP

) tried to find a half-way position between objectivism and subjectivism which has the benefits but avoids the difficulties of both.

Moral judgements, he argues in

HSEP

, are in reality judgements about the good of society and its individual members. Such judgements embody or express the fairly widespread community of feeling in a given society about what, generally speaking, is in everyone’s interests. And this is a matter about which there can be sensible debate based on a scientific or at least rational understanding of the world. This belief in the possibility of rational resolutions to moral dilemmas often threatened to desert Russell when he contemplated human folly, but he clung to it nevertheless.

The fundamental data of ethics, Russell says, are feelings and emotions. Accordingly, ethical judgements are disguised expressions of our hopes, fears, desires, or aversions. We judge things to be good when they satisfy our desires. Therefore the general good – the good of society as a whole – consists in the total satisfaction of desire, no matter by whom enjoyed. By the same token the good of any section of society consists in the overall satisfaction of its members’ desires; and an individual’s good consists in the satisfaction of his personal desires. On this basis one can define ‘right action’ by saying that it is whatever, on any given occasion, is most likely to promote the general good (or if it concerns only an individual, that individual’s good); and this in turn gives us our explanation of moral obligation, the idea that there are things that one ‘ought’ to do; which is, simply, that one ought to do the right thing as thus understood (

HSEP

25, 51, 60, 72).

Russell of course recognizes that there are difficulties with this account, and discusses a number of them. For example: the definition of ‘good’ as ‘satisfaction of desire’ invites the obvious objection that some desires are evil, and that satisfying them is a worse evil. Russell considers the example of cruelty. Can it be good if someone wishes to make another suffer? And is it not even worse if he succeeds in carrying out his wish? Russell says that his definition does not imply that such a state of affairs is good. For one thing, it involves the frustration of the victim’s desires, for the victim naturally desires to avoid suffering at the perpetrator’s hands. And for another, society at large will not in general desire that its members should be victims of cruelty, and so its desires in this respect will be frustrated too. Accordingly there will be a great preponderance of unfulfilled desire when cruelty is perpetrated, thus making it bad.

Another difficulty for Russell’s account is that desires can conflict. He responds by saying that this places a demand on us to choose desires that will be least likely to compete with one another. Borrowing a technical term from Leibniz, Russell calls consistency between desires their ‘compossibility’. Good and bad desires can then be defined as those which are compossible with, respectively, as many and as few other desires as possible.

Russell devotes a chapter to the question whether judgements such as ‘cruelty is wrong’ are simply disguised expressions of subjective attitude. As noted, this question is important, and it troubled Russell deeply. He arrived at what might be called his ‘sociological’ answer – that moral value is the product of a kind of social consensus – after considering alternative possibilities offered by ethical debate.

The problem can be stated by noting that the chief difference between ordinary factual discourse and moral discourse is the presence in the latter of terms like ‘ought’, ‘good’, and their synonyms. Are these terms part of the ‘minimum vocabulary’ of ethics, that is, both indefinable and fundamental to any understanding of ethical concepts; or can they be defined in terms of something else, for example feelings and emotions? And if this latter, are the sentiments in question those of the individual who makes a moral judgement, or do they have a reference more general – to the desires and feelings of mankind? (

HSEP

110–11).

In discussing these questions Russell notes that when we examine moral disagreements over what ought to be done in a given case, we find that many of them derive from disagreement over what will result from this or that course of action. This shows that moral evaluations turn on estimates of outcomes, and that therefore we can define ‘ought’ by saying that an act ought to be performed if, among all acts possible in the case, it is the one most likely to produce the greatest amount of ‘intrinsic value’ (an expression Russell uses as a more precise substitute for ‘good’).

Is ‘intrinsic value’ definable? Russell thinks it is. ‘When we examine the things to which we are inclined to attach intrinsic value,’ he says, ‘we find that they are all things that are desired or enjoyed. It is difficult to believe that anything would have intrinsic value in a universe devoid of sentience. This suggests that “intrinsic value” may be definable in terms of desire or pleasure or both’ (

HSEP

113). Since not all desires can be intrinsically valuable because desires conflict, Russell refines the notion so that intrinsic value is understood as a property of the ‘states of mind’ desired by those who experience them.

With this adjustment, Russell offers the following summary of his view. As a rule our approval or otherwise of given acts is dependent on what consequences we think they are likely to have. The consequences of acts we approve we call ‘good’, their opposites ‘bad’. The acts themselves we call ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ respectively. What we ‘ought’ to do is whatever is a right act in the circumstances, that is, whatever will produce the greatest balance of good.

Of these points the first carries greatest weight. If moral evaluation is a matter of what people approve and disapprove, are we not marooned in the subjectivist dilemma, without rational grounds for committing ourselves to the wrongness of, say, racism, intolerance, cruelty, and the rest? Russell’s answer is that there is as a matter of fact widespread agreement among people about what is desirable. He agrees with Henry Sidgwick that the acts which people generally approve are those which produce most happiness or pleasure. If this includes the satisfaction of intellectual and aesthetic interests (‘if we were really persuaded that pigs are happier than human beings, we should not on that account welcome the ministrations of Circe’; some pleasures are

inherently

preferable to others), then we have our escape from subjectivism; for this view gives us statements about what ought to be done which are not merely disguised optatives or imperatives, and thus have truth-value; but which, nevertheless, rest on facts about our feelings and the satisfaction of our desires. Facts about our feelings underlie the definition of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’, and facts about satisfaction of desires underlie the definition of ‘intrinsic value’. Thus Russell claims success in having articulated a half-way position between objectivism and subjectivism which, at the same time, has practical credentials in a quite straightforward sense, as providing a way of evaluating not just actions of the kind typically at issue in moral debates, but social customs, laws, and government policies.