Salonica, City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims and Jews 1430-1950 (36 page)

Read Salonica, City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims and Jews 1430-1950 Online

Authors: Mark Mazower

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Greece, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

Over the next century, fires and urban redevelopment entirely erased all trace of the edifice. Because Miller failed to note its location or to draw a plan of the site, we have no means of knowing where it stood or what its function was. And the caryatids themselves? Initially intended to enrich the royal collection of Napoleon III, a latecomer to the museum business, they were only deposited in the Louvre once the idea of an imperial Musée Napoleon III was abandoned. Since Miller failed to number the pieces he did deliver, the curators had to reconstruct the ensemble blind. “When the Miller marbles were sent to France and brought to the Louvre,” wrote the

conservateur des antiques

there in the 1920s, “they were unfortunately not accompanied by any kind of regular inventory.” In fact, the Louvre’s own initial catalogue made matters worse by mixing up pieces from Salonica with others from Thasos, and by failing to note that some pieces Miller had collected in Salonica had gone astray. After the Second World War, the reconstruction was dismantled, and the pieces were dispersed through the museum.

22

The Miller affair left its mark on the Ottoman authorities and after it was over they tightened up their supervision of the foreign archaeologists. They did not prevent their activities; far from it, there were probably more serious investigations undertaken after 1880 than at any time previously. But, as one scholar reported, “they have become sufficiently alive to the possible value of archaeological finds no longer

to allow the wholesale deporting that has often been practised, more especially by the French.” In 1874 legislation controlled the foreign acquisition of antiquities for the first time, for officials had become conscious of their cultural and financial value. The regime began to collect on its own account, and major finds were reserved for the Imperial Archaeological Museum that Abdul Hamid established in 1880 in a fine neo-classical building in Istanbul. In Salonica the municipality began excavating the statues and sarcophagi uncovered in building works and stored finds in the courtyard of the governor’s mansion, before sending the best pieces on to the capital. “In the past we did not appreciate the value of antiquities,” declared Münif Pasha, minister of education, at the museum’s opening. “A few years ago an American took enough [of them] from Cyprus to fill an entire museum. Today, most [objects] in European and American museums are from the stores of antiquities in our country.”

23

Despite these words, the traffic in real—and even more, in forged—goods continued. More worryingly, the sultan saw antiquities as a means of cementing international goodwill and was inclined to disregard the protests of his own museum director. In this way, Kaiser Wilhelm, a close ally of Abdul Hamid, acquired the marble ambo from which Saint Paul was said to have preached and had it brought to Berlin. It was only one of the many tangible benefits reaped by the Berlin Museum from the burgeoning German-Ottoman friendship. Although there were plans to build a museum in Salonica itself, these were still on paper only when the Greek army took the city in 1912.

24

T

HE ARCHAEOLOGISTS WERE MORE INFLUENTIAL

than perhaps they knew. For by bringing to light the extensive remains of ancient settlement, they reinforced the view, which as we have seen was so pronounced throughout the age of European travel, that the real city of Salonica lay beneath the Ottoman surface. After 1912, this led Greek (and foreign) planners to reshape the urban landscape, demolishing old seventeenth- and eighteenth-century buildings—today it is doubtful whether half a dozen survive—to clear space for new focal points—the Roman forum, the Arch of Galerius and the main churches—which would bring the ancient city into visual alignment with the modern one. Neo-Hellenic modernization was thus also an assertion of neo-classicism. The origins of this linkage lay in those Western attitudes exemplified by so many travellers and their obsession with antiquity.

Most of them had regarded the picturesque sight of the minarets to be the only positive aspect of Ottoman rule. Otherwise they blamed the Turks for the city’s squalor, and openly doubted their ability to modernize or reform. “The Turks, although they have borrowed much and destroyed more, have built nothing,” asserted Abbott. Even though they could not miss the signs of change which transformed the fin-de-siècle city—the demolition of the walls, the spread of new suburbs, the docks and railway—Europeans saw these only as ugly blots on the Oriental canvas they had come to admire. In the increasingly racialized vocabulary of the late nineteenth century, “Turks” were seen as Asiatic and essentially nomadic, the antithesis of European civilization and by implication, merely a transient presence on European soil. The idea that the empire might be modernizing itself, and transforming its cities and societies, struck only a few. Yet the great historical irony is that even as Victorian travellers were insisting more and more upon the hopelessly immobile character of late Ottoman Salonica, it was in the process of changing faster and more dramatically than at any other time in its history. Its population rose from around 30,000 in 1830 to 54,000 in 1878, 98,000 in 1890 and 157,900 by April 1913. The city was leaving the Western stereotypes far behind.

25

11

In the Frankish Style

D

ID ANYWHERE IN FIN-DE-SIÈCLE EUROPE

offer the tourist such a taste of the Orient? Zepdji’s postcards featured women in their

yashmaks

and

feredjés

, cafés with elderly turbaned men smoking their

narghilés

, belly-dancers, snake-charmers and street musicians. Early colour photographers posed Jewish women in their bright aprons and fur-lined jackets, their hair braided and cased in the traditional green silk snoods. Yet none of these ethnographic curiosities were particularly striking to local people. On the contrary, faced with a younger generation raised on a diet of Viennese operetta, buffet dances, aperitifs at the Café Olympos, balloonists, bicycles and moving pictures, many felt the city was changing bewilderingly fast. “The old dress has completely disappeared,” wrote a local scholar in 1914. “The Greeks were the first to adopt the European style. The Jews were quick to follow their example. The Donmehs and Turks imitated the Jews … Today, apart from the occasional Albanian in his fustanelle and the hand-me-downs of some villager who has strayed into town, the quay at Salonica, with its cafés, hawkers, inns and cinemas, its passers-by rigged out in those dreadful bowler hats, is scarcely different from any European port in the Western Mediterranean.”

1

European visitors to the empire had not failed to notice the intrusion of their own values. “The immobile Orient is no longer immobile,” wrote the

Guide Joanne

, “and in the presence of this peaceful invasion of the European spirit, the old world of Islam feels itself renewed.” But most doubted that the consequences would ever be beneficial. The French engineer Auguste Choisy predicted the attempt to graft European civilization onto Ottoman traditions was doomed to failure: blending cultures, or races, would only foster degeneration.

“Generally speaking, the Greek peasant degenerates in Asia, the Turkish in Europe,” wrote Urquhart. “So the Turk in contact with Europeans and the Europeans among the Turks. The two systems, when in juxtaposition, and not under the control of a mind that grasps both, are mutually destructive … Ill-will and hatred are the result of intercourse without reciprocal sympathy and respect.”

2

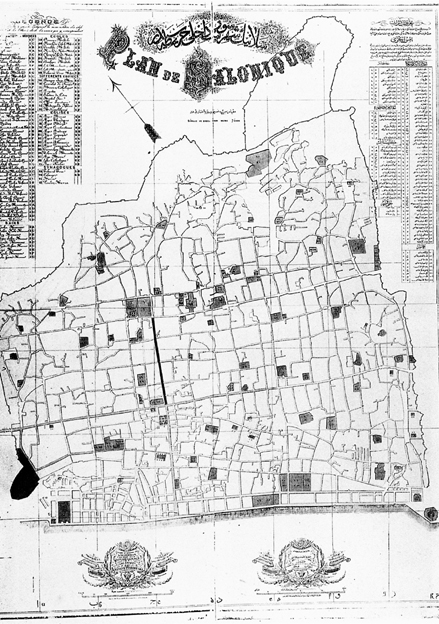

The first map of the Ottoman city, 1882, showing the new sea frontage

Yet such opinions said more about the prejudices of Western visitors than they did about Ottoman realities. In the final third of the nineteenth century, “Frankish” values spread quickly throughout Salonica—more quickly perhaps than anywhere else in the empire. A wealthy Greek and Jewish “aristocracy” challenged the power of their own religious leaders: founding schools and newspapers, they subsidized European languages, learning and ideas. Their spreading influence rested on a new prosperity, the fruit of an extraordinary period of growth which saw the city treble in size as its trading activities boomed. For Salonica was escaping the gravitational pull of Istanbul and establishing profitable connections with western Europe. Entire stretches of its walls were demolished, exposing its frontage to the sea and allowing its harbour to be extended. And as the city opened itself to the outside world so its own appearance was transfigured by new suburbs, wide boulevards, factories, retail department stores and trams. For the first time, the city enjoyed municipal government. Indeed, it was perhaps only now that the city acquired a consciousness of itself. Under the leadership of its bourgeoisie, Ottoman Salonica embraced Europe.

C

OMMUNICATIONS

I

N 1836 THE FIRST SMALL STEAMBOAT

, the

Levant

, was sent by a British company. Shortly after this the British signed a commercial convention with the Porte to liberalize trade, and Abdul Mecid established a Ministry of Trade and a Council of Public Works. The abolition of monopolies and the freeing-up of the grain trade allowed the city to forge new trading linkages with the dynamic industrializing economies of western Europe. As the Austrian Lloyd Company, the Ottoman Steam Navigation Company and the French Messageries Maritimes established weekly steamer services linking Salonica to Istanbul and the Adriatic, the slow transformation of its prospects began.

They were not, initially, very bright. After the boom of the early

nineteenth century, the Levant trade had stagnated. When an American frigate called into the port in 1834, the captain reported that the scenery was more enticing than its commercial potential. The wooden quay was mouldering away, the harbour itself was uncharted and sandbanks were slowly silting up the mouth of the Vardar. Piracy deterred movement by sea. “The outrages which the pirates commit in this gulf are of a nature beyond description,” wrote the British consul in 1827, “and I am sorry to say that [as] their number increases daily, their inhumanity will prove very detrimental to our trade.” “The Greek pirates still infest some Bays in this Gulf,” reported his American counterpart six years later. The following year a Greek schooner from Smyrna was captured and the crew murdered. The advantages of getting rid of the menace were obvious. “There cannot be a doubt,” wrote the American consul in 1834, “that when the advantages of the commerce of Salonica shall be better known, and our merchant vessels shall be protected from the Pirates which almost constantly infest the Gulf, a trade highly beneficial to the interest of the United States will be carried out.”

3

As a result of joint international naval operations, in which the Greek and Ottoman fleets worked together, the pirates were cleared from the northern Aegean over the next few years and the expansion of commerce got under way. The tonnage of shipping entering Salonica increased five-fold in just three decades. Sail gave way to steam, and regionally based Greek and Ottoman ship-owners lost out to the French and Austrians who dominated the traffic to and from the main European ports. The sea still carried voyagers eastwards—Adolphus Slade’s fellow-travellers in 1830 to Izmir included five Albanians, a Greek tobacco trader, local Turkish women on the

haj

, a Maronite bound for Lebanon and an Egyptian slave dealer with nine “negresses” whom he had failed to sell in Salonica. Coffee and spices still came from Yemen, and the

Azizieh

steamer docked regularly from Alexandria. But the city’s orientation was changing. The slave trade, which had linked the city with suppliers from Circassia and the Ukraine to Sudan, Benghazi and the Barbary coast, was targeted by British abolitionists: although it was not formally outlawed until 1880, even before then, slaves had to be smuggled in as domestic servants, or landed furtively outside the town before dawn on the wooden landing-stage in the Beshchinar gardens.

4

Meanwhile, as local raw materials were exported to western Europe from the hinterland, European manufactures poured in: Manchester cottons and Rouen silks, beer from Austria, watches and jewellery

from Switzerland, wine and marble, worsteds and cutlery from Germany, French stationery and perfumes, drugs, billiard tables, cabinets and fancy upholstery. The British consul noted the growing demand for “British-made shoes and boots, felt and straw hats, men’s flannels, cotton and linen shirts and vests, handkerchiefs, ties, stockings and socks.” Between 1870 and 1912 the city’s imports nearly quadrupled in value.

Land communications lagged behind. “Sometimes you overtake long strings of camels led by the invariable little donkey, and laden with bales of merchandise, passing slowly along the road,” noted a traveller in 1860. “And occasionally a train of heavy Bulgarian carts drawn by buffaloes; the wheels of which are never greased, creaking, groaning and screeching in a manner quite inconceivable in civilized countries.” After the Crimean War, the Ottoman authorities tried to improve or inaugurate new “imperial” roads. However, the cash-strapped central government could not afford to provide funds, and the provincial authorities were forced to conscript peasant labour and raise taxes locally. Quickly it became clear that no roads would ever be finished, or if they were finished maintained, by such methods. “My estate is only eight miles from Salonica,” wrote one land-owner in 1877 “and five years ago the magnificent highway road to Serres was made and passes close to the property. The road has never been touched from that day to this and is now impassable for wheeled carriages. The result is that although I have an excellent market only eight miles off, I must send all my grain to it on pack-animals.”

5