Salonica, City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims and Jews 1430-1950 (37 page)

Read Salonica, City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims and Jews 1430-1950 Online

Authors: Mark Mazower

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Greece, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

It would take a long time before the regional road system was substantially improved—not until French and British technology arrived with the Army of the Orient in the First World War. In the meantime, what finally ended the city’s isolation by land was rail. In 1852 the German scientist and traveller Ami Boué had proposed the construction of four major lines in the Ottoman Balkans, and over the coming years, local entrepreneurs and diplomats promoted the advantages of rail connections. In 1864 two English engineers surveyed the route between Salonica and Monastir, and finally in 1871, work finally began on a line from Salonica to Pristina: the first section of just over sixty miles was opened, after tortuous progress, in July 1872. The line was extended northwards to Skopje and more than a decade later it was linked up to the Serbian network and central Europe. “In a little while,” wrote a local journalist in January 1886, “any one of us will be able, on the third night after leaving our city, to hear the finest musicians in the

Grande Opera

in Paris, and the merchant in a few days to equip his stores with

Parisian or Viennese products.” When, two years later, the connection with Europe was made, the train from Paris was greeted by a crowd of thirty thousand excited bystanders. “For half a mile before the train came to the main station the track was lined on both sides with dense rows of people,” wrote a Prussian reporter. “Never in my life have I seen such an uproar, such a waving of shawls and hands. This reached a tremendous crescendo as the train finally came to a halt in the station, where the noise reached a fortissimo which literally deafened us. It is impossible to describe the shouting and the crush.”

6

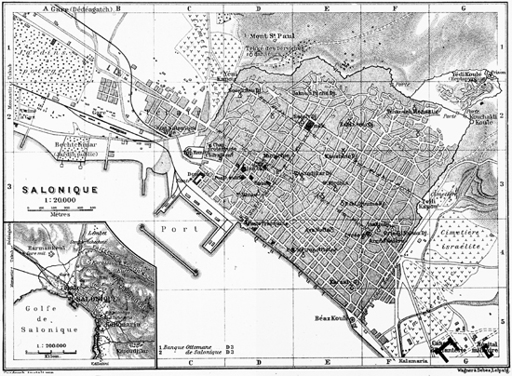

The late Ottoman city and its surroundings,

c.

1910

A second track connected Salonica with the important administrative, commercial and military town of Monastir, and a third line later linked it to Istanbul. Abdul Hamid himself had hesitated before granting permission for this but the Ottoman general staff wanted to be able to move troops between Asia Minor and the Balkans. Opened in April 1896, the line proved its value the following year when it became “the right arm of the Ottoman government” in the war with Greece, and the secret of its unexpected victory. Keeping away from the coast, it meandered through the plains of Thrace and the foothills of the Rhodope mountains. Even today, the stretch after Xanthi that follows the Nestos River into its twisting roadless gorge—travelled now only by a few back-packers, gypsies and Turkish tobacco-merchants—makes one of the most dramatic rides in Europe.

7

In just over twenty years, therefore, foreign speculators and engineers equipped European Turkey with more than seven hundred miles of track. The

shimen defair

as they were known in the city may have been a mixed blessing for Salonica’s hinterland since they diverted traffic away from the roads, and probably helped the latter fall into even greater disrepair. On the other hand, they had a catalytic effect on the city itself, linking it more tightly than ever before to the world beyond.

8

A letter travelling from Salonica to Paris in the early part of the nineteenth century took a good month, no different from Roman times. By the 1860s this had been cut to about two weeks by steam-boat, and rail cut it further to sixty-three hours. By this point, the city was also in telegraphic communication with England, Austria, Italy and Istanbul. As a result, foreign reporters—a litmus test of international accessibility—started to arrive: first spotted in the Near Eastern crisis of 1877–78, their numbers increased during the Greco-Turkish war of 1897—Bigham of the

Times

, Gueldan of the

Morning Post

, Peel of the

Daily Telegraph

, Fetzer, the military correspondent for

Über Land und Meer

—and by the beginning of the twentieth century, they were coming in

droves to report every twist and turn of the Macedonian Struggle. Later the trains would carry others too—troops heading inland, and refugees heading out. Without rail, it would scarcely have been possible to engineer the huge forced movements of entire peoples that were to transform the city beyond all recognition over the following seventy years.

All this had taken place thanks to the Ottoman economy’s opening to European capital and expertise, and the speculative frenzy that accompanied this. “Travel where you will, in any part of Turkey,” wrote James Baker in 1877, “and in every small town you will find many of the wealthiest people who can think and talk of nothing else but Turkish bonds; and there is quite a feverish excitement on the subject.” Talked up, the prospects grew brighter and brighter, despite the imperial government’s large debts. In the early 1880s, pundits predicted that the economy of Macedonia would be transformed by rail: the Serbian trade would be diverted southwards, perhaps even the India mail might be wrested from Brindisi. The British consul forecast that once the Skopje line was linked to the Austrian railway system, Salonica would become the leading centre of commerce in the Levant. “Is it necessary to recall how the entire press was publishing on the exceptional situation of this city, and on the importance which it must inevitably assume once in direct communication with the Balkan powers and central Europe?” wrote the French consul in 1892. In the event, Izmir, Alexandria and even Trieste outstripped the Macedonian port. Yet the dreams and ambitions were important, for they expressed the apparently boundless confidence that was turning a new force in the city—its bourgeoisie—into the motor of municipal change, cultural revolution and economic growth.

9

S

CHOOLING THE

B

OURGEOISIE

I

N 1768 THERE WERE ONLY ONE HUNDRED

European residents; by the end of the nineteenth century there were nearly ten thousand. The quarter where they had lodged since Byzantine times was close to the port and the new wheat market, with its warehouses and broking agents. In 1854, before the commercial boom had really got under way, Boué found “houses made of stone, two storeys high, with glass windows and painted blinds. In some of them you might well imagine yourself in Europe.” By the end of the century, the district

contained the French and German churches, the Deutsche Klub, the Théâtre Français, banks, post offices and expensive hotels, travel bureaux, consulates, bookshops and chemists. It was here that for much of the century lived the Charnauds, Chasseauds and Abbotts, bearers of a way of life which through inter-marriage and long residence combined European and Ottoman traditions, languages and occupations.

10

More important (and richer) even than the Franks themselves were those local honorary Europeans—the prosperous Greek and Jewish merchants under consular protection—whose close commercial and intellectual connections with Europe and prominent position in their own communities within the city made them natural cultural intermediaries. In 1873, the cream of this elite—the Jews Hugo Allatini, Joseph Misrachi, Samuel Modiano and the Greek Perikles Hadzilazaros—combined forces with the British consul John Blunt and the Levantine banker John Chasseaud to found the

Cercle de Salonique

in order to provide facilities “for society and travellers.” The idea had probably been Blunt’s but the club clearly met a need for it lasted for more than eighty years. It provided a model of sociability that had not existed before—a luxurious meeting-place for the city’s new cross-confessional upper class, and for important foreign visitors. By 1887 there were 159 members, including Jews, Greeks, Germans, Italians, Turks, Armenians and others. Among them were Alfred Abbott (Jackie Abbott’s nephew), the tobacco-merchant and future mayor Husni Bey, Dimitris Zannas, a Greek doctor to the city’s upper crust, the police chief Selim Bey, and the city’s most famous lawyer,

maître

Emmanuel Salem, a long-standing member of the governing council of the Jewish community and secretary of the new Lawyers’ Guild. These were the city’s new masters—professional men, army officers, diplomats, bankers, land-owners and traders—and they insisted in the club regulations that political or other passions should not be allowed to disrupt the fundamental spirit of social harmony and comradeship.

11

The chief battles they were waging—and from the 1870s winning—were with their own archbishops and rabbis. The Allatinis and Fernandes families among the Jews, the Hadzilazaros, Rongottis and Prasakakis among the Greeks, were not merely the presentable face of the city—its “society”—for Western visitors of standing, but more importantly, they were the architects of a shift of power within the city from the old elites to the new commercial class whose aspirations they embodied. It was the generation of Moses Allatini (1800–1882), educated at Pisa and Florence, the man described by one historian as

the “real regenerator of the Jewish community of Salonica” and one of the city’s first industrialists, which initiated the challenge of the moneyed classes to their own religious leaders.

This clash was produced directly by the contradictory consequences of the Ottoman legislative reforms. As we have seen, one effect of the 1839 Gulhané decree, which aimed to promote equality between the empire’s religious communities, was to throw the weight of the Ottoman state behind the metropolitan and the chief rabbi, the recognized leaders of their communities. But at the same time, the freeing-up of trade, the consolidation of private property rights and the growth of the city’s economy, especially after the Crimean War, increased the fortunes and the political weight of its traders and businessmen. Conservative religious leaders had not bothered much to bridge the cultural cleavage between them. Chief Rabbi Molho, for instance, had tried to play off his support among the poor to criticize the merchant notables for their religious laxity. He had excommunicated a youthful member of the Fernandes family for going hunting with the city’s consuls and eating non-kosher meat; his successor locked up Jewish printers on charges of printing unauthorized books, in an effort to affirm the power of the rabbinical censors and stamp down on secular learning. But in 1856 an imperial decree introduced the principle of representative government within the empire’s

millets

, leaving it to members of those communities to decide how they wished to govern themselves. Thereafter, the key issue for both Christians and Jews was to establish how much power religious leaders would be forced to hand over to the lay members of the new communal councils. When Abdul Mecid visited Salonica in 1859, he granted a personal audience only to those Jewish notables “with whom he could converse in French,” leaving the rabbinate out in the cold. Under pressure from merchants, doctors and lawyers of liberal views, crucial changes were slowly made at the top of the religious leadership: the increasingly conservative Ascher Covo was replaced as chief rabbi on his death in 1874 by the more flexible Abraham Gattegno—elected for the first time by a vote of the new General Assembly of the community—and the wealthy stratum of the Jewish bourgeoisie eventually persuaded his successor—with the aid of the intervention of the Ottoman governor—to implement the administrative reforms agreed some fifteen years earlier, by adopting communal statutes which limited the chief rabbi’s role in communal affairs. Similar struggles went on between “aristocratic” and “democratic” factions among the city’s Greeks over the introduction of the

General Regulations for the Orthodox communities of the empire: there too the new influence granted to lay leaders of the community accompanied a narrowing of the juridical and fiscal powers of the religious hierarchy.

12

The struggle for communal authority was fought out over many areas—care for the poor and sick, the upkeep of cemeteries, the administration of religious foundations themselves—but the key battleground was education. For religious learning alone was no longer enough. Ties with the West meant also that local merchants needed employees to be familiar with modern languages, mathematics and geography. The notable Jewish families pushed hard for the use of Italian and French books in the old Talmud Torah in the 1840s. When they got nowhere, they obtained a firman to found their own pilot school, run by a German rabbi whom the local rabbis regarded as an impious foreigner. But the real educational revolution among Salonican Jewry only came in 1873 when the same notables opened a branch of the Paris-based Alliance Israélite Universelle—the very embodiment of French Enlightenment liberalism—in the teeth of fierce opposition from the elderly chief rabbi. It was an extraordinary success: by 1912 the Alliance was responsible for educating more than four thousand pupils, over half the total number of children in Jewish schools. “I was once invited to an annual gathering of the Israelite Alliance,” wrote a British journalist during the First World War. “There were many hundreds of Jews there, male and female, and a great many of them were once removed only from the street porter class. But they rattled off French as if they had been born to it.” Not only were the majority of the city’s Jewish children receiving an education outside the control of the religious authorities, but they were receiving it on the basis of the principles of contemporary French republicanism. Such a trend had a corrosive effect on the authority of the chief rabbi, and helped turn him slowly into more and more of a purely religious and spiritual figurehead.

13