Salt (36 page)

B

Y THE LATE

eighteenth century, more than 3,000 French men, women, and even children were sentenced to prison or death every year for crimes against the gabelle. The salt law in France, as would later happen in India, was not the singular cause of revolution, but it became a symbol for all the injustices of government.

In 1789, the French revolted, declaring the establishment of a National Assembly. When King Louis XVI tried to send troops against this revolutionary legislature, a mob attacked the Bastille and an armed revolution began. That same year, the revolutionary legislature repealed the gabelle. Some in the Assembly had argued for a low salt tax universally applied. But in the end the Assembly voted for no salt tax at all, not even bothering to replace this mainstay of state revenues with another source of income.

On March 22, 1790, the National Assembly, calling the salt tax “odious,” annulled all trials for violation of the gabelle and ordered all those charged, on trial, or convicted to be set free.

Louis, accused of conspiring with Austrians and Prussians to overthrow the revolution, was beheaded. His wife, Marie Antoinette, who loved choucroute, was also beheaded, as were many of the Swiss soldiers of the Garde Royale. They also had acquired the court taste for choucroute and numerous inns had sprung up near the Palais Royal, where they had spent their meal breaks, feasting on choucroute with sausages and salted meats. The tradition of restaurants serving midday choucroute in that part of Paris continues to this day.

I

N 1804,

N

APOLÉON

Bonaparte, who had risen to head of the revolutionary army and then rose to first consul, became emperor of the French. He reinstated the gabelle but without an exemption for Brittany.

Their salt no longer having a competitive advantage, the paludiers, instead of being slightly better off than the average French peasant, were now among the poorest. They continued to wear large, floppy, three-cornered hats in the style of eighteenth-century peasants. Visitors found this a picturesque part of Brittany. Novelist Honoré de Balzac abandoned poetic restraint in his description of the paludiers and their treeless salt marsh, writing that they had “the grace of a bouquet of violets” and asserting that it “was something a traveler could see nowhere else in France.” He compared the area to Africa, and in the age of French colonialism many followed, comparing the impoverished Breton paludiers to Tuaregs, Arabs, and Asians. Faced with an onslaught of affluent French who found them exotic, the paludiers made souvenirs: ceramic plates depicting their dress and dolls in paludier costume fashioned out of seashells. Le Bourg de Batz became Batz-sur-Mer, Batz-by-the-sea, to make this salt town by the swamp sound more suitable for tourism.

Watercolor of a paludier from an 1829 book by H. Charpentier illustrating the clothing worn by salt workers in the Guérande area.

Musée des Marais Salants, Batz-sur-Mer

The salt cuisine of Brittany showed its poverty. Breton cooking was based on the few simple crops that paludiers could grow in their clay-bound soil, mostly potatoes and onions, which absorbed a salty taste from the seaweed in the soil.

Ragoût de berniques,

literally a stew made of nothing, was in fact made of potatoes, carrots, and onions. While France was one of the last European nations to accept the eating of potatoes, Brittany was one of the first potato-eating parts of France. Almost forty years earlier Antoine-Augustin Parmentier had persuaded the royal family to promote the eating of potatoes, a man named Blanchet launched a potato-eating campaign in Brittany. Soon after that, a cleric named de la Marche distributed potatoes to poor parishioners and was nicknamed

d’eskop ar patatez,

the potato bishop. After the Revolution, paludiers supplemented their diminished income by growing potatoes, which were boiled in brine that left a fine salt powder on the skin—

patate cuit au sel.

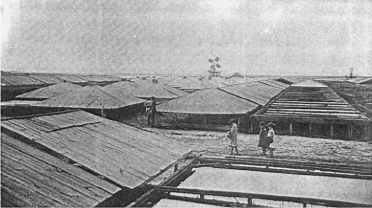

A nineteenth-century postcard of sardines being salted in Pouliguen, near Batz.

Musée des Marais Salants, Batz-sur-Mer

A Breton expression was “Kement a zo fall, a gar ar sall”—Everything that is not good asks to be salted. Everything from meat to butter to potatoes was salted. Salt was Brittany’s cheapest product, the one everyone could afford. Another Breton proverb was “Aviz hag holen a roer d’an nep a c’houlenn”—Advice and salt are available to anyone who wants it.

Kig-sall,

salted pig, usually was made with the ears, tail, and feet—sometimes better cuts if they could be afforded—put in a barrel with lard and salt, and kept two or three months until preserved like ham. And there was

oing,

known in Breton as

bloneg,

which was nothing more than pork fat rendered with salt and pepper, dried in the open air on paper, and then smoked in a fireplace. A slice of oing was added to a vegetable soup as a substitute for meat.

I

N THE 1870S

, when the area was connected to the national railway system, the floppy, three-cornered hats vanished. The same railroad system favored eastern France, where the new industries such as steel were, and made the salt of Lorraine more accessible than sea salt. The gabelle remained a part of French administration until it was finally abolished in the newly liberated France of 1946.

Honoré-Gabriel Riqueti, the Comte de Mirabeau, the man who had defied Louis XVI by opening the National Assembly, said, “In the final analysis, the people will judge the revolution by this fact alone—does it take more or less money? Are they better off? Do they have more work? And is that work better paid?”

T

REATIES ARE USUALLY

imperfect solutions, and the Treaty of Paris did not end all hostilities between the new United States and Britain. The United States was embargoed from any British goods, and British colonies were not permitted to engage in U.S. trade. The Turk Islands, the present-day Turks and Caicos, including Salt Cay, became havens for Americans still loyal to Britain. In Cape Cod the price of salt rose from fifty cents a bushel to eight dollars.

In 1793, in a postwar economy that was still demanding salt, another Sears, Reuben Sears, a Cape Cod carpenter, invented a roof that slid open and shut on oak rollers, allowing sea salt to now be made efficiently from March until November. The vats were exposed while the sun was shining, but after sunset and whenever it began to rain the roofs were rolled over the vats. Though the saltworks were privately owned, the Cape Cod communities considered them so essential to the general well-being that when clouds began to darken the daytime sky, men and women would run out to roll all the roofs closed and children would be sent from the schools to help, and the coastline would rumble like nearby thunder from the sound of hundreds of oak wheels.

Other books

Love in a Bottle by Antal Szerb

Carol Finch by The Ranger

Geek Heresy by Toyama, Kentaro

The Vanished by Tim Kizer

Westward Moon by Linda Bridey

Winterlands 2 - Dragonshadow by Hambly, Barbara

Alone by Francine Pascal

Ain't No Wifey by J., Jahquel

Blurring the Line by Kierney Scott

The Laura Cardinal Novels by J. Carson Black