Salt (40 page)

The Union army generally had ample supplies, and its rations included salt, salt pork, occasionally bacon, and both fresh and salted beef. Here too reality did not quite live up to the ration list. The salt beef, of which a Union soldier was issued one pound, four ounces per day, was greenish in color and unlovingly nicknamed by the troops “salt-horse.” John Billings, a Union veteran, writing about the rations after the war, mentioned numerous unpalatable recipes such as

ashcake,

which was cabbage stuffed with salted cornmeal and water and baked in ashes.

Four days after the war began on April 12, 1861, President Abraham Lincoln ordered a blockade of all southern ports. The blockade was enforced until the war ended in 1865. The North was able to put enormous resources into maintaining it. At its height in 1865, 471 ships with 2,455 guns were being used exclusively to enforce the blockade.

The blockade caused shortages and the accompanying high prices of speculators for not only salt but many basic foods. In 1864, potatoes cost $2.25 a bushel in the North and $25 a bushel in Richmond. Initially, the high prices posed more of a problem than scarcity. This recipe for salted beef appeared early in the war, when salt was still available but pork was unaffordable.

When Bacon gets too costly.

A gentleman who has tried the following recipe warmly recommends it: Cut the beef into pieces of the proper size for packing, sprinkle them with salt lightly, and let them be twenty four hours, after which shake off the salt and pack them in a barrel. In ten gallons of water, put four gallons salt, one pound saltpeter, half pound black pepper, half-pound allspice, and half gallon of sugar. Place the mixture in a vessel over a slow fire and bring to a boil. Then take it off and, when it has cooled pour it over the beef sufficient to cover it and fill the barrel. After the lapse of three or four days, turn the barrel upside down to be sure the beef is all covered by brine. If the beef is good, it will make it fit to set before a king. The beef will keep for a good long time. During the scarcity and exorbitant price of bacon our readers might try the recipe and test its virtue.—Albany Patriot,

Georgia, October 31, 1861

When salt first started to become scarce in the Confederacy, owners of large plantations in coastal areas reverted to the Revolutionary War practice of sending their slaves to fill kettles with seawater for evaporation. But it soon became apparent that both the blockade and the war were to be far more serious than had been imagined. The small amount of salt produced from these kettles was not going to solve their problems.

At the outbreak of war, a 200-pound sack of Liverpool salt sold at the pier in New Orleans for fifty cents. After more than a year of the blockade, in the fall of 1862, six dollars a sack was considered a bargain in Richmond. By January 1863, the price in Savannah, a major port until the blockade, was twenty-five dollars for a sack.

The Union quickly realized that the salt shortage in the South was an important strategic advantage. General William Tecumseh Sherman, one of the visionaries of a modern warfare in which cities are smashed and civilians starved, wanted to deny the South salt. “Salt is eminently contraband, because of its use in curing meats, without which armies cannot be subsisted.” he wrote in August 1862.

When the war finally ended, and Generals Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee sat down to talk, Lee said that his men had not eaten in two days and asked Grant for food. According to some observers, when the Union supply wagons were pulled into sight, the defeated soldiers of the famished Army of Northern Virginia let out a cheer.

I

N 1861, THE

western counties of Virginia organized into West Virginia, and Union general Jacob Dolson Cox marched in from Ohio up the valley of the Great Kanawha River. By July 1861, he controlled the entire valley, including the saltworks. It was one of the first major blows to the South. But in the fall of 1862, Confederate loyalists asked for volunteers to liberate the saltworks, and in a surprise attack a force of 5,000 Confederates drove the Union soldiers back to the Ohio River so quickly that they did not have time to destroy the saltworks before they retreated.

The Union learned a lesson from this: In the future, when they captured saltworks, they destroyed them. If the saltworks were brine wells, as in Kanawha—which Cox retook in November 1862, never to be retaken by the South—they broke the pumps and shoved the parts back down the wells. This contrasts with the Confederates, who when they took a saltworks celebrated having captured it and went into production.

A clerk in the Confederate War Department, blaming Confederate president Jefferson Davis’s lack of resolve for the loss of Kanawha, wrote in his diary:

The President may seem to be a good nation-maker in the eyes of distant statesmen, but he does not seem to be a good salt-maker for this nation. The works he has just relinquished to the enemy manufacturer: 7000 bushels of salt per day—two million and a half per year—an ample supply for the entire population of the Confederacy, is an object adequate to the maintenance of an army of 50,000 in that valley. Besides, the troops that are necessary for its occupation will soon be in quarters, and quite as expensive to the government as if in the valley. A Caesar, Napoleon, a Pitt, and a Washington, all great nation-makers, would have deemed this work worthy of their attention.

A

S THE WAR

went on, the Union army attacked saltworks wherever it found them, from Virginia to Texas. The Union navy attacked salt production all along the Confederate coast. At first, saltworks prospered on the Florida Gulf Coast because the area was largely untouched by the war. By the fall of 1862, the Union noticed the size and importance of Florida Gulf salt production along the entire coast, but especially between Tampa, on the mid–gulf coast, and Choctawhatchee Bay, on the western end of the panhandle, near Alabama. The saltworks were usually hidden a few miles up inlets and were barely visible from the gulf. Even if detected, the inlets were difficult for gunboats to navigate.

On September 8, 1862, the Union vessel

Kingfisher

approached the saltworks at St. Joseph Bay on the panhandle under a flag of truce and gave the Confederate salt workers two hours to abandon the site. Taking with them four cartloads of salt, the workers left. Three days later the Union navy destroyed the works.

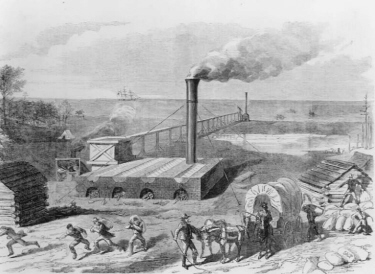

An illustration from

Harper’s Weekly

of workers on the Florida Gulf Coast fleeing with salt as the crew of the Union ship

Kingfisher

is about to destroy the saltworks on September 15, 1862.

Collection of the New York Historical Society

On October 4, 1862, marines from the Union gunboat

Somerset,

moving farther down the coast, raided saltworks near Cedar Key on Suwannee Bay. After about twelve shells were fired, the salt workers raised a white flag. A landing crew met no resistance and destroyed several saltworks. But when they approached the one from which the white flag was flying, twenty-five men concealed in the rear of the building opened fire. Half the Union forces were wounded before reinforcements arrived from a nearby Union steamship. After driving the Confederate fighters into retreat, the Union landing party destroyed the boilers, an odd assortment of makeshift contraptions, and set the houses on fire. Some of the boilers and kettles were made of such thick iron that they had to fire howitzers at them to blow them apart. “The rebels here needed a lesson, and they have had it,” said the commander of the

Somerset

.

The Union navy continued to attack saltworks on the Florida coast, burning houses, blowing apart equipment. By 1863, it had destroyed more than $6 million worth of saltworks back up at the panhandle in the St. Andrews Bay area. But saltworks, although easily destroyed, are just as easily and inexpensively rebuilt. In three months, many of the destroyed works were back in production.

Northern salt was smuggled into the South along with weapons, especially in Tennessee. Salt was also a common item of blockade runners. Liverpool salt was shipped to the Mexican port of Veracruz and from there to Brownsville, Texas, and into the Confederacy.

Mississippi governor John J. Pettus came up with an elaborate scheme to import 50,000 sacks of French salt in exchange for cotton brought to the shore of Lake Pontchartrain. The exchange was to be one bale of cotton for ten sacks of salt, arranged through the French and British consuls, to whose governments the Union blockade largely meant a loss of commerce. But though 500 bales of cotton were turned over to France, the French never delivered the salt.

W

ORKING CONDITIONS AT

the improvised wartime saltworks of the Confederacy were even worse than those at Kanawha had been. At the saltworks that sprung up along the Tombigbee River, a few miles north of Mobile, Alabama, new wells were dug every day by people who had come from as far away as Georgia. During the war, southerners traveled hundreds of miles to the seacoast or a brine spring to make salt. The area along the Tombigbee, protected by a Confederate fort in case the Union took Mobile, was marked by a vast traffic jam of carts and wagons filled not only with pots and boilers and other potential salt-making equipment but with poultry and other food—anything that could be traded for salt. Overseers drove the mule teams, and slaves followed behind on foot.

Some slaves chopped wood for fuel, the air shaking with hundreds of axes thudding into wood, while others dug fifteen-foot wells. In the beginning of the war, anyone could come and spend a few weeks making salt, but by 1862, leases regulated by the Alabama legislature were required. By then the woods had been thinned out, and there was a fuel shortage. Shallow pans were designed for more efficient evaporation over two-foot-high furnaces with grates and iron doors. This equipment could make twenty to thirty-five bushels of salt a day, depending on the salinity of the water. Salt makers found that the deeper the well, the saltier the water, and began boring deeper into the bottoms of the original wells.

Other books

The Last Tsar: Emperor Michael II by Donald Crawford

Last Summer by Rebecca A. Rogers

Soulstealers: The Chinese Sorcery Scare of 1768 by Philip A. Kuhn

Rock-a-Bye Bones by Carolyn Haines

Silent Hearts (Hamilton Stables 3) by Melissa West

The Divine Whisper by Rebekah Daniels

The Dog by Joseph O'Neill

The Carrot and the Stick by C. P. Vanner

Ravens Shadow 02 - Tower Lord by Anthony Ryan

Enid Blyton by MR. PINK-WHISTLE INTERFERES