Sara Paretsky - V.I. Warshawski 10 (27 page)

Read Sara Paretsky - V.I. Warshawski 10 Online

Authors: Total Recall

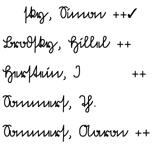

The script was still hard to make out, but I could

read Hillel Brodsky, I or G Herstein, and Th. and Aaron Sommers—although it

looked like Pommers I knew it had to be my client’s uncle. So this was a list

of clients from the Midway Agency—that seemed like a reasonable assumption.

What did the crosses mean? That they were dead? That their families had been defrauded?

Or both? Perhaps Th. Sommers was still alive.

The dogs, restless from five hours inside, got up and

wagged their tails at me. “You guys think we should get in motion? You’re

right. Let’s go.” I shut down my system, carefully slid the original of the

fragment into my own case, and took Fepple’s briefcase with me back to the car.

The clock was ticking and I had business-hours errands

to run. I gave the dogs a chance to relieve themselves but didn’t take the time

to run them before driving out the O’Hare corridor to Cheviot Labs, a private

forensics lab I often use. I showed the fragment of paper to the engineer who’s

helped me in the past.

“I know metal, not paper, but we’ve got someone on

staff here who can do it,” he said.

“I’m willing to pay for a priority job,” I said.

He grunted. “I’ll talk to her. Kathryn Chang. One of

us’ll call you tomorrow.”

I was just ahead of the afternoon rush, so I kept the

increasingly restless dogs in the car until we got to Hyde Park, where I threw

sticks into the lake for them for half an hour. “Sorry, guys: bad timing to

take you two today. Back in the car with you.”

It was four, when a lot of duty rosters change; I

drove over to the Hyde Park Bank building. Sure enough, the same man who’d been

here Friday was on duty. He looked at me without interest when I stopped in

front of his station.

“We kind of met on Friday afternoon,” I said.

He looked at me more closely. “Oh, yeah. Fepple said

you’d been harassing him. You harass him to death?”

He seemed to be joking, so I smiled. “Not me. It was

on the news that he’d been shot, or shot himself.”

“That’s right. They say the business was going down

the toilet, which doesn’t surprise me. I’ve worked here nine years. Since the

old man died I bet I could count the evenings the young one worked late. Must

have been disappointed with the client he saw on Friday.”

“He came back with someone after I left?”

“That’s right. But must not have amounted to anything

after all. I suppose that’s why I didn’t see him leave: he stayed up there and

killed himself.”

“The man who came in with him—when did he leave?”

“Not sure it was a man or a woman—Fepple came back

along with a Lamaze class. I think he was talking to someone, but I can’t say I

was paying close attention. Cops think I’m derelict because I don’t photograph

every person that passes through here, but, hell, the building doesn’t even

have a sign-in policy. If Fepple’s visitor left at the same time as the

pregnant couples, I wouldn’t have noticed them special.”

I had to give up on it. I handed him Fepple’s canvas

bag, telling him I’d found it on the curb.

“I think it might belong to Fepple, judging by the

stuff inside. Since the cops are being a pain, maybe you could just drop it in

his office—their problem to sort out if they ever come back here again.” I gave

him my card, just in case something occurred to him, along with my most

dazzling smile, and headed for the western suburbs.

Unlike my beloved old Trans Am, the Mustang didn’t

handle well at high speeds—which wasn’t a problem this afternoon, because we

weren’t going anywhere very fast. As the evening rush built, I sat for long

periods without moving at all.

The first leg of the trip was on the same expressway

I’d taken when I went to see Isaiah Sommers on Friday. The air thickened along the

industrial corridor, turning the bright September sky to a dull yellowish grey.

I took out my phone and tried Max, wondering how Lotty and he were faring after

last night’s upheavals. Agnes Loewenthal answered the phone.

“Oh, Vic—Max is still at the hospital. We’re expecting

him around six. But that horrid man who came to the house last night was around

today.”

I inched forward behind a waste hauler. “He came to

the house?”

“No, it was worse in a way. He was in the park across

the street. When I took Calia out for a walk this afternoon he came over to try

to talk to us, saying he wanted Calia to know he wasn’t really a big bad wolf,

that he was her cousin.”

“What did you do?”

“I said he was quite mistaken and to leave us alone.

He tried to follow us, arguing with me, but when Calia got upset and began to

cry he started to shout at us—imploring me to let him talk to Calia by himself.

We ran back to the house. Max—I called Max; he called the Evanston police, who

sent a squad car around. They moved him off, but—Vic, it’s really frightening.

I don’t want to be alone in the house—Mrs. Squires didn’t come in today because

of the party yesterday.”

The car behind me honked impatiently; I closed a

six-foot gap while I asked if she really had to stay in Chicago until Saturday.

“If this horrid little man is going to be stalking us,

I might see if we can get on an earlier flight. Although the gallery I went to

last week wants me to come in on Thursday to meet with their backers; I’d hate

to lose that opportunity.”

I rubbed my face with my free hand. “There’s a service

I use when I need help bodyguarding or staking out places. Do you want me to

see if they have someone who can stay in the house until you go home?”

Her relief rushed across the airwaves to me. “I’ll

have to talk to Max—but, yes. Yes, do that, Vic.”

My shoulders sagged when she hung up. If Radbuka was

turning into a stalker, he could become a real problem. I called the Streeter

Brothers’ voice mail to explain what I needed. They’re a funny bunch of guys,

the Streeter Brothers: they do surveillance, bodyguarding, and furniture

moving, with Tom and Tim Streeter running a changing group of nine, including,

these days, two well-muscled women.

By the time I finished my message, we had passed into

the exurbs. The road widened, the sky brightened. When I left the tollway, it

was suddenly a beautiful fall day again.

Grieving Mother

H

oward

Fepple had lived with his mother a few blocks west of Harlem Avenue. These

weren’t the suburbs of great wealth but of the working middle class, where

ranch houses and colonials sit on modest plots and neighborhood children play

in each other’s yards.

When I pulled up in front of the Fepple home, only one

car, a late-model navy Oldsmobile, sat in the drive. Neither news crews nor

neighbors were paying their respects to Rhonda Fepple. The dogs strained to

follow me from the car. When I locked them in, they barked their disapproval.

A flagstone path, whose stones were cracked and

overgrown with weeds, curved away from the driveway to a side entrance. When I

rang the bell, I saw that the paint on the front door had peeled loose in a

number of places.

After a long wait, Rhonda Fepple came to the door. Her

face, with the same carpet of freckles as her son’s, held the blank, stunned

look most people wear after a harsh blow. She was younger than I’d expected.

Despite the grief that was collapsing her inside her clothes, she had only a

few lines around her red-stained eyes, and her sandy hair was still thick.

“Mrs. Fepple? I’m sorry to bother you, but I’m a

detective from Chicago with a few questions about your son.”

She accepted my identity without even wanting a name,

let alone some identification. “Did you find out who shot him?”

“No, ma’am. I understand you told the officers on the

morning shift that Mr. Fepple didn’t own a gun.”

“I wanted him to, if he was going to stay in that

creepy old building, but he just laughed and said there wasn’t anything in the

agency anyone would want to steal. I always hated that bank, those halls with

all the little turnings off them, anyone could lie in wait for you there.”

“The agency wasn’t doing very well these days, I

understand. Was it more prosperous when your husband was alive?”

“You’re not trying to say what they told me this

morning, are you? That Howie was so depressed he took his own life? Because he

wasn’t that kind of boy. Young man. You forget they grow up.” She patted the

corners of her eyes with a tissue.

It was comforting somehow to know that even a dreary

specimen like Howard Fepple had someone who mourned his death. “Ma’am, I know

this is a really hard time for you to try to talk about your son, with the loss

so fresh, but I want to explore a third possibility—besides suicide or a random

break-in. I’m wondering if there was anyone who might have specifically had a

quarrel with your son. Had he talked to you about any conflicts with clients

lately?”

She stared at me blankly: thinking new thoughts was

hard in her grief-drained state. She stuffed the tissue back into the pocket of

the old yellow shirt she was wearing. “I suppose you better come in.”

I followed her into the living room, where she sat on

the edge of a sofa whose cabbage roses had faded to a dull pink. When I took a

matching armchair at right angles to her, dust bunnies bounced along the walls.

The new piece in the room, a tan Naugahyde recliner parked in front of the

thirty-four-inch television, had probably belonged to Howard.

“How long had your son been working at the agency,

Mrs. Fepple?”

She twisted her wedding ring. “Howie wasn’t much

interested in insurance, but Mr. Fepple insisted he learn the business. You can

always make a living in insurance, no matter how bad times are, he always said.

That’s how the agency survived the Depression, he was always telling Howie

that, but Howie wanted to do something—well, more interesting, more like what

the boys—men—he went to school with were doing. Computers, finance, that kind

of thing. But he couldn’t make a go of it, so when Mr. Fepple passed away and

left the agency to him, Howie went ahead and tried to make it work. But that

neighborhood has gone steep downhill since when we used to live there. Of

course, we moved out here in ’59, but all Mr. Fepple’s clients were on the

South Side; he didn’t see how he could move the agency and look after them.”

“So you lived in Hyde Park when you were growing up?”

I asked, to keep the conversation going.

“South Shore, really, just south of Hyde Park. Then

when I got out of high school I went off to work as a secretary to Mr. Fepple.

He was quite a bit older, but, well, you know how these things go, and when we

found Howie was on the way, well, we got married. He had never married

before—Mr. Fepple, I mean—and I guess he was excited at the idea of a boy to

carry on—his father started the agency—you know how men are about things like

that. When the baby came, I stayed at home to look after him—back then we

didn’t have day care, you know, not like now. Mr. Fepple always said I spoiled

him, but he was fifty by then, not much interested in children.” Her voice

trailed away.

“So Mr. Howard Fepple only started work at the agency

when his father died?” I prompted. “How did he learn the business?”

“Oh, well, Howie used to work there weekends and

summers, and he spent four years there after college. He went out to Governors

State, got a degree in business. But like I said, insurance wasn’t really his

cup of tea.”

The mention of tea galvanized her into thinking we

should have something to drink. I followed her into the kitchen, where she

pulled a Diet Coke out of the refrigerator for herself and handed me a glass of

tap water.

I sat at the kitchen table, pushing aside a banana

peel. “What about the agent who worked for your husband, what was his name?

Rick Hoffman? Your son seemed to admire his work.”

She made a face. “I never took to him. He was such a

fussy man. Everything had to be just so. When I worked there he was always

criticizing me because I didn’t keep the file drawers the way he wanted them

organized. It was Mr. Fepple’s agency, I told him, and Mr. Fepple had a right

to set up files the way he wanted them, but Mr. Hoffman insisted I get all his

files arranged in this special way, like it was some big deal. He did these

little sales, burial policies, that kind of thing, but the way he acted you’d

think he was insuring the pope.” She waved her arm in a vague gesture, making

the dust bunnies bounce.