Saying Grace (19 page)

Authors: Beth Gutcheon

There was silence.

“Did you hurt her feelings, and did you know that’s what you were doing?”

“At least I didn’t tell stupid lies, like I’m too stupid to tell…”

“SSSt,” Rue cut her off. “Apologizing does not include justifying yourself. Do you know what to do or do I have to show you?”

136 / Beth Gutcheon

After a long pause, Jennifer raised her eyes to Lyndie’s face, and said in a low voice, “Lyndie, I’m very sorry that I hurt your feelings.”

“Thank you,” said Rue. “Carly?”

Carly apologized to Lyndie, and then Malone.

Rue turned to Lyndie.

“What?” said Lyndie.

“Your turn.”

“I didn’t do anything!” Rue looked at her for a long time. She saw a thoroughly miserable child, but beyond that, she wasn’t sure what she was looking at. At last she said, “You tried to get your friend in trouble.”

“She pushed me….”

“SSSt,” Rue cut her off. “You tried to get your friend in trouble.

Now you can insist on being right, and be lonely, or you can apologize, and maybe get your friend back. Your choice.” She and Lyndie looked at each other for a long moment.

“Jennifer,” said Lyndie, almost inaudibly, “I’m sorry I tried to get you in trouble.”

“Thank you,” said Rue. She looked at the four little girls standing before her. Their faces had changed. It was as if saying the words had changed the furious feelings they had brought into the fray.

“I’m proud of you all, that’s a hard thing to do. Much harder than fighting and holding grudges. Is there something you all like to do that you could do together right now?” Rue knew perfectly well that there was nothing fifth-grade girls liked more than hanging out complaining about bossy, unfair grown-ups, and she was pretty sure they could find some sheltered place to do it.

I

t was a Monday afternoon in mid-November. Carpool was over and the campus was quiet. Rue was in her office doing the payroll for Bill Glarrow, who was on vacation, when she heard a scream from the parking lot.

Cynda Goldring was not an hysterical woman, but when Rue reached her, she was crying. Emily was there seconds later, and the two of them stood with her beside her car as she blew her nose and apologized.

“I know, I’ve completely wrecked my mascara,” she said. She had, indeed. There were dark, wet puddles under her eyes. “Sorry. I’m okay now. I shouldn’t have screamed.”

“What happened?” Emily asked. She touched Cynda’s shoulder, comforting, but Cynda shrugged it off. She was back in control.

“You won’t understand why I made such a fuss. It just surprised me.”

“What?”

“Get in the driver’s seat and look in the rearview mirror.”

Emily climbed in and did as she was told. At first she inhaled sharply, then swung around to look at what she was seeing in the mirror.

“That is absolutely

sick

,” she said, scrambling out of the car.

Rue got in. She looked in the rearview mirror and saw written in black ink on the leather above the rear window were the words,

Die,

You Bitch

.

As Emily had done, she whirled around to look straight on. The writing was careful, skillful mirror writing.

Rue got out. “Was the car locked?”

Cynda shook her head no.

“Nevertheless…some little beast came out here in daylight, bold as brass, and climbed into your car and took his time doing that.”

138 / Beth Gutcheon

Cynda nodded.

Emily asked, “Do you have any idea who?”

Cynda shook her head. “The eighth graders are terrors. But I

like

the bad ones! They all know that!”

“You’re not having special trouble with anyone?” Cynda shook her head.

Rue and Emily looked at each other. Now what should they do?

Should they urge her to ignore it? Should she be frightened? Who would do a thing like that?

She stood looking miserable for a moment. Then she said, “I didn’t need to make such a fuss. I’m not usually such a baby. It’s just that Elliot and I decided to get divorced this morning.”

“What?” cried Emily.

Rue whispered, “Oh, no!”

“It’s all right,” said Cynda. “We were hardly speaking to each other. We didn’t even like to pass each other in the hall. It’s just that now that it’s over and he’s going I feel a little…jumpy.”

“Maybe Elliot did it,” said Emily.

“Not a chance, he’s not clever enough,” said Cynda.

“This is somebody bright and really malicious,” said Rue.

“I guess I better start locking my car,” Cynda said. She climbed in.

“Are you sure you’re all right? Do you want me to follow you home?” asked Emily.

“No, really. I’m fine.” Cynda turned on the engine and pulled out of her parking space rather suddenly. She drove off leaving Rue and Emily staring at each other.

“This job is a laugh a minute,” said Emily to Rue.

“Tell me about it.” They stood in the sunshine.

“Did you know Cynda and Elliot were unhappy?” Emily asked.

“I noticed they were never together. He never came to faculty lunches, or anything.” They started walking back to Home.

“What’s he like?” Emily asked. “Maybe he’d like me.”

Rue laughed.

“I wasn’t kidding,” said Emily.

“I know you weren’t,” Rue said, and briefly patted Emily’s arm.

“Don’t worry, we’ll find somebody for you.”

T

he weeks leading up to the Christmas break had become a complicated time in the life of The Country School. Under the Miss Plums, all had been serene. There was a Christmas pageant telling the story of the Annunciation and Nativity from the point of view of the Angels. The first and second graders performed in the entr’act-es, dressed in nightgowns and spangly wings, but the action was controlled from Gabriel’s headquarters, which looked a lot like the newsroom of a big city paper.

An angel would run in dressed in a big suit. “Boss, they only got as far as Bethlehem and it looks like the Lord is going to have to sleep on the ground.”

“Oh, we can do better than that,” Gabriel would say, taking his feet off the desk. “Get down there and disguise yourself as a pig or something, and tell the animals to take care of them.” Then the lights would move to the stable scene. A pig would appear on stage and whisper to the oxen and the sheep, and pretty soon a nice clean manger full of straw would be ready to receive the infant. At the end of the performance Miss Carla Plum would remind the audience that In Those Days angels appeared on earth dressed as shepherds of the first century just as today angels were all around you, looking exactly like ordinary people. And who knows what they wear in heaven, she would say, and the audience would laugh as their children appeared dressed as sheep, shepherds, and newspapermen for curtain calls.

Miss Lourdes Plum then would play the piano and lead the school in Christmas carols. There was a wassail bowl after the program, and Miss Carla Plum appeared in a Santa Claus costume with a pillow under her tunic and a cottonball beard taped to her face. She handed out sweets and oranges and told everyone they should look for miracles every day, not just at Christmas.

Now there was no Christmas celebration at Country. Instead 140 / Beth Gutcheon

there was a Festival of Holiday customs, featuring costumes, music, song, and story from three foreign countries each year, if possible represented by families in the school. This year the countries were Nicaragua, Tibet, and Armenia, and preparations were by no means going smoothly. The Nicaraguan family was staunchly pro-Contra and had run afoul of another mom on the committee whose brother had helped prosecute Oliver North. The mom from Lhasa knew very little of the holiday folkways of her country; she had grown up in Nepal in a house the size of Vaux Le Vicomte, in which the king of Tibet was being held prisoner on the second floor. She was a charming woman, beloved by all and now married to a venetian blind salesman, but the exotic holiday treats she remembered best from her childhood, which she reconstructed from a yellowing recipe written in Hindi by the family cook, turned out to be brownies. The Missirlians were preparing a huge map labeled Armenia, chunks of which the rest of the world tended to call Iran, Turkey, or Russia.

They were also preparing tableaux vivantes depicting the Armenian holocaust and diaspora. This was actually quite popular, but it had caused unfestive feelings in the Hikmet family, Turkish-Americans whose five children had been attending Country for a span of sixteen years.

Rue and Mike Dianda were drinking mugs of herb tea in Mike’s office. It was the end of a long day.

“What else?” Rue asked.

“Well Pat Moredock seems to be going crackers. She is keeping a diary of her grievances, and she’s started stuffing pages from it into my mailbox every day,” said Mike. “Also, she went to the store to buy a couple of hacksaw blades and some construction paper, and came back with receipts for two hundred and seventeen dollars.”

“Worth of hacksaw blades?”

“No, she bought twenty soldering irons, and a few bales of cop-perfoil, and she had her whole trunk full of sheets of stained glass.”

Rue covered her face with her hands.

“Bill Glarrow made her take it all back, but she’s bitter. She says the teachers teaching academics can spend money without asking first. I pointed out that they can’t, but never mind.”

“She thought she’d teach stained glass in an elementary school?

Can you imagine the insurance?”

Saying Grace / 141

“Insurance, nothing. We’d have to build an entirely separate studio. You get tiny little shards of glass in everything when you cut glass.”

“Speaking of insurance, the Lozattos are now suing us for fifty thousand one hundred and seventy-five dollars.”

“What?”

“Yes. They asked that Patsy’s tuition be returned, so I sent it back….”

“Minus one hundred seventy-five dollars for processing. The contract

says

it’s unrefundable.”

“And Jerry Lozatto signed the contract. The insurance company wants to settle the suit, but Ann Rosen is so mad now that she won’t.”

“Good for her.”

“And someone in the eighth grade took forty dollars from Cynda Goldring’s wallet.”

They sat in silence, finishing their tea. “I better go talk to Pat Moredock,” said Rue, sounding as if it was the last thing she wanted.

“Take Bonnie with you,” said Mike.

“Great idea, thank you. I will.”

Rue and Bonnie found Pat Moredock cleaning up her studio. It was a large bright room lined with gray and orange tiles, with art projects stacked on every surface. On the long workbenches in the center of the room lay gray life masks, eerie eyeless visages that the sixth graders made by applying surgical cast material to each other’s Vaselined faces. The masks were drying now, after which the students would paint them so that the masks became a statement of identity. Sometimes the most apparently sunny children would paint their masks in dark, disturbing colors, or color one-half one way and the other side quite different, or paint on strange scars.

“So interesting,” said Bonnie to Pat as she walked from dead face to dead face. “Since sixth graders all wear masks anyway.”

“Do they?” said Pat. She had been expecting a more conventional compliment. She was used to people making a great fuss about the sunny color that flooded the room, the artwork and materials everywhere, the feast of possibilities she provided the children.

142 / Beth Gutcheon

“I think so. They’re so frightened of standing out of the crowd, and yet angry that we don’t see how they’re special.”

“I think they’re all special,” said Pat stiffly. She went back to wiping down tables and putting the caps back on the jars of tempera paints.

“Oh, yes, but do we see in what individual ways? Behind these little blank faces?” She gestured to the masks.

“Oh yeah, oh yeah,” said Pat, with her back to the room. Pat was a big woman, with iron-gray hair, inexpertly curled. She wore large loose shirts and skirts, and in the studio, a denim apron. She moved soundlessly in thick-soled brown Hushpuppies. She was very busy putting things in order. Rue couldn’t interpret her tone, or for that matter, her meaning. Was she agreeing with Bonnie? Or brushing her off?…

There was a pause. Rue, listening, found herself looking at a shelf of cubbies stacked with drawings. She took down a pile and began to leaf through them. They were designs, or in some cases pictures, that incorporated letters of the alphabet. Here was a clever one in which a large K had become a tree with a rake leaning against it.

“You already washed those once,” Bonnie said next. “The brushes.”

“I did not,” said Pat, quite aggressive.

“You did,” said Bonnie gently. “I watched you.”

“Would you mind telling me what you’re doing here? I know my time isn’t as valuable as the Latin teacher’s or the math teacher’s, but it’s mine, and I’m fond of it.” Rue went on paging through the drawings. That sentence didn’t make much sense, she thought. She’s so angry about something that it’s making her speechless.

“I’m sorry,” said Bonnie. “We did come for a reason. We want your advice.”

“Oh,” said Pat. “All right. Do you need me to sit down?”

“Do what you have to do.”

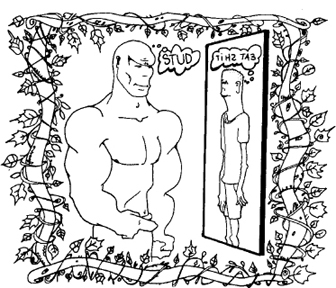

Suddenly Rue felt herself go white. She was looking at a drawing that was very different from the others in the stack, which she judged to be by eleven- or twelve-year-olds. It was a picture of an Arnold Schwarzenegger-like character looking into a mirror. It was more a cartoon than a portrait but it was extraordinarily well done.