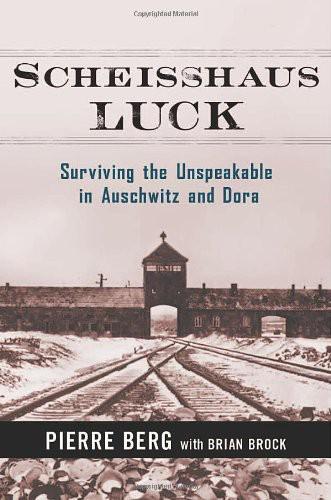

Scheisshaus Luck

Authors: Pierre Berg; Brian Brock

Tags: #Europe, #Political Prisoners - France, #1939-1945, #Auschwitz (Concentration Camp), #World War II, #World War, #Holocaust, #Political Prisoners, #Political, #Pierre, #French, #France, #Berg, #Personal Memoirs, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #Military, #Personal Narratives, #General, #Biography, #History

Scheisshaus Luck:

Surviving the Unspeakable

in Auschwitz and Dora

Pierre Berg

AMACOM

SCHEISSHAUS LUCK

Surviving the Unspeakable in Auschwitz and Dora

Pierre Berg

with Brian Brock

AMERICAN MANAGEMENT ASSOCIATION

New York • Atlanta • Brussels • Chicago • Mexico City • San Francisco Shanghai • Tokyo • Toronto • Washington, D.C.

Special discounts on bulk quantities of AMACOM books are

available to corporations, professional associations, and other

organizations. For details, contact Special Sales Department,

AMACOM, a division of American Management Association,

1601 Broadway, New York, NY 10019.

Tel.: 212–903–8316. Fax: 212–903–8083.

Web site:

www.amacombooks.org

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative

information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the

understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal,

accounting, or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert

assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person

should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Berg, Pierre.

Scheisshaus luck : surviving the unspeakable in Auschwitz and Dora / Pierre Berg with

Brian Brock.—1st ed.

p.

cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-8144-1299-2

1. Berg, Pierre.

2. Auschwitz (Concentration camp)

3. Political

prisoners—France—Biography.

4. World War, 1939–1945—Personal narratives,

French.

I. Brock, Brian.

II. Title.

D805.5.A96B465

2008

940.53’18092—dc22

[B]

2008003779

᭧

2008 Pierre Berg.

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

This publication may not be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system,

or transmitted in whole or in part,

in any form or by any means, electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior written permission of AMACOM,

a division of American Management Association,

1601 Broadway, New York, NY 10019.

Printing Hole Number

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

To all my comrades who didn’t make it

This page intentionally left blank

C O N T E N T S

v

vi

CONTENTS

In 1947, two years after Pierre Berg escaped from a Nazi concentration camp, he began writing down his experiences. His goal was to record his observations of those terrible eighteen months before he forgot them. He had no intention of ever publishing them. None-theless, he gave these recollections a title,

Odyssey of a Pajama

.

Pierre wrote his memoir in French, but since he was now living in America, he had it translated by a UCLA grad student. He then allowed a couple of people to read his odyssey, and they convinced him that a magazine or book publisher might be interested in his story. In 1954, after two rejection letters, one from the

Saturday

Evening Post

and the other from

Harper’s

, Pierre put his concentration camp memoir aside and got on with his new life in Los Angeles.

More than fifty years later, I was supplementing my income as a struggling writer by working the concession stand at a playhouse in Beverly Hills. Pierre, now retired, was working as an usher. During a Sunday matinee performance, Pierre and I struck up a conversation on the writer’s life. He informed me that he had written something about his time in the camps. A few days later he handed me a 145-page manuscript. As I read

Odyssey of a Pajama

for the first time, it was obvious that Pierre’s experiences in the camps were vii

viii

FOREWORD

unique and compelling. His voice was frank and was tinged with irony, irreverence, and gallows humor. The situations he found himself in were horrifying, heartbreaking, perverse, and oddly enough, sometimes funny. I was fascinated by his tale and by the young man in it. I believed that Pierre’s story would be a major addition to the Holocaust literature.

We decided to work together to amplify the original manuscript, which we did through both oral and written interviews. One of the problems I found was that many of the events that the young Pierre had written about lacked crucial details that would immerse the reader in that world and in what he had suffered. After my initial interviews, it also became evident that some of the incidents the teenager had endured or witnessed did not appear in the manuscript. It was no surprise to me that the original manuscript was incomplete: It was written as a private journal by a very young man who, in l947, had no way to judge the significance of what he had just experienced. Also, because his mother was typing the manuscript for him, Pierre had left things out in order to spare her the details of some horrific events he had been involved in.

As Pierre’s collaborator I felt that I had two major responsibilities. First, I needed to ensure that his personality came across on the page. Second, I wanted to be sure that we expressed as vividly as possible the emotional impact of the daily life-and-death struggle in Auschwitz. This latter goal proved to be the more difficult.

It is well known that those who have been brutalized and violated block those memories as a survival mechanism. Pierre was no different. He was resistant to talking about the emotions that gripped him during those eighteen months, saying many times that he didn’t feel anything. But the details he related to me, and his gestures and expressions in regard to those events, said otherwise.

When he was unwilling to delve into the emotions of a specific incident, I would present him with differing emotional points of view, and this would often ignite a dialogue that enabled us to capture his emotional state at that time.

We had many arguments, especially when I aggressively tried FOREWORD

ix

to elicit Pierre’s reactions and emotions. I pushed him relentlessly because I thought it was important that his story be told fully. It is a credit to Pierre’s strength of character that he never wavered in his resolve that this story be told completely—and that he never took a swing at me.

Concentration camp inmates all wore triangles of varying colors to distinguish the different classes of prisoners. Pierre’s was a red triangle (political prisoner). His story is vital because it is a reminder that it wasn’t just yellow triangles (Jews) who were rounded up and killed by the Nazis. The Jewish people suffered the most, but Gypsies, Communists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, homosexuals, and other men, women, and children from every country in Europe were imprisoned and perished alongside them.

Scheisshaus Luck

will remind everyone that none of us—no matter what race, religion, nationality, or political conviction—are immune from becoming a victim of genocide.