Schild's Ladder (30 page)

Authors: Greg Egan

This was too easy. “I'd use a compass,” Tchicaya said. “And if I didn't have a compass, I'd use the stars. Wherever I went, I could always find the same bearing.”

“You think that's the best way to carry a direction with you? Reproducing its compass bearing?”

“Yes.”

His father drew a small arrow on the globe, close to the north pole, pointing due north. Then he drew another on the opposite side of the pole, also pointing due north. The two arrows shared the same compass bearing, but anyone could see that they were pointing in opposite directions.

Tchicaya scowled. He wanted to claim that this was just a perverse exception to an otherwise reasonable rule, but he wasn't sure that was the case.

“Forget about north and south,” his father said. “Forget about the stars. This arrow is your only compass; there is nothing else to steer by. You must take it with you. Now tell me how.”

Tchicaya stared at the globe. He drew a path leading away from Baake. How could he duplicate the arrow as he moved? “I'd draw another arrow, each time I took a step. The same as the one before.”

His father smiled. “Good. But how would you make each new one the same?”

“I'd make it the same length. And I'd make it parallel.”

“How would you do that?” his father persisted. “How would you know that the new arrow was parallel to the old one?”

Tchicaya was unsure. The globe was curved, its geometry was complicated. Maybe it would be simpler to start with a flat surface, and then work his way up to the harder case. He summoned a translucent plane and drew an arrow in black. On command, his Mediator could duplicate the object faithfully, anywhere else on the plane, but it was up to him to understand the rules.

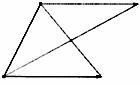

He drew a second arrow and contemplated its relationship with the first. “They're parallel. So if you join the two bases and the two tips, they make a parallelogram.”

“Yes. But how do you

know

that they make a parallelogram?” His father reached over and skewed the second arrow. “You can tell that I've ruined it, just by looking, but what is it that you're looking for when you see that?”

“The distances aren't the same anymore.” Tchicaya traced them with his finger. “From base to base and tip to tip, it's different now. So to make the second arrow a copy of the first, I have to make sure that it's the same length, and that its tip is as far away from the first one's tip as the bases are from each other.”

“All right, that's true,” his father agreed. “Now suppose I make things more difficult. Suppose I say you have no ruler, no tape measure. You can't measure a distance along one line and duplicate it on another one.”

Tchicaya laughed. “That's too hard! It's impossible, then!”

“Wait. You can do this: you can compare distances along the same line. If you go straight from A to B to C, you

can

know if B is exactly half the journey.”

Tchicaya gazed at the arrows. There was no half journey here, there was no bisected line in a parallelogram.

“Keep looking,” his father urged him. “Look at the things you haven't even drawn yet.”

That clue gave it away. “The diagonals?”

“Yes.”

The diagonals of the parallelogram ran from the base of the first arrow to the tip of the second, and

vice versa

. And the diagonals divided each other in two.

They worked through the construction together, pinning down the details, making them precise. You could duplicate an arrow by drawing a line from its tip to the base you'd chosen for the second arrow, bisecting that line, then drawing a line from the base of the first arrow, passing through the midpoint and continuing on as far again. The far end of that second diagonal told you where the tip of the duplicate arrow would be.

Tchicaya regarded their handiwork with pleasure.

His father said, “Now, how do you do the same thing on a sphere?” He passed the globe over to Tchicaya.

“You just do the same thing. You draw the same lines.”

“Straight lines? Curved lines?”

“Straight.” Tchicaya caught himself. Straight lines, on a globe? “Great circles. Arcs of great circles.” Given any two points on a sphere, you could find a plane that passed through both of them, and also through the center of the sphere. The arc of the equatorsized circle formed where the plane cut through the surface of the sphere gave the shortest distance between the two points.

“Yes.” His father gestured at the path Tchicaya had drawn, snaking away from their town. “Go ahead and try it. See how it looks.”

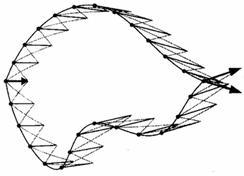

Tchicaya copied the arrow once, a small distance along the path, using the parallelogram construction with arcs of great circles for the diagonals. Then he had his Mediator repeat the process automatically, all the way to the end of the path.

“That's it,” Tchicaya marveled. “We've done it.” A lattice of diagonals ran along the path, marking the way, carrying the arrow forward. No compass, no stars to steer by, but they'd found a way to copy the arrow faithfully from start to finish.

“It's beautiful, isn't it?” his father said. “This is called Schild's ladder. All throughout geometry, all throughout physics, the same idea shows up in a thousand different guises. How do you carry something from here to there, and keep it the same? You move it step by step, keeping it parallel in the only way that makes sense. You climb Schild's ladder.”

Tchicaya didn't ask if the prescription could be extended beyond physics; as an answer to his fears, it was only a metaphor. But it was a metaphor filled with hope. Even as he changed, he could watch himself closely, and judge whether he was skewing the arrow of his self.

“There's one more thing you should see,” his father said. He drew a second path on the globe, joining the same two points but following a different route. “Try it again.”

“It will be the same,” Tchicaya predicted confidently. “If you climb Schild's ladder twice, it will copy the arrow the best way, both times.” It was like being asked to add up a dozen numbers twice, grouping them in different ways. The answer had to be the same in the end.

“So try it again,” his father insisted.

Tchicaya complied.

“I've made a mistake,” he said. He erased the second ladder, and repeated the construction. Again, the second copy of the arrow at the end of the path failed to match the first.

“I don't understand,” Tchicaya complained. “What am I doing wrong?”

“Nothing,” his father assured him. “This is what you should expect. There's always a way to carry the arrow forward, but it depends on the path you take.”

Tchicaya didn't reply. He'd thought he'd been shown the way to safety, to persistence. Now it was dissolving into contradictions before his eyes.

His father said, “You'll never stop changing, but that doesn't mean you have to drift in the wind. Every day, you can take the person you've been, and the new things you've witnessed, and make your own, honest choice as to who you should become.

“Whatever happens, you can always be true to yourself. But don't expect to end up with the same inner compass as anyone else. Not unless they started beside you, and climbed beside you every step of the way.”

Tchicaya made the globe vanish. He said, “It's late. I'd better go to sleep now.”

“All right.” His father stood as if to leave, but then he reached down and squeezed Tchicaya's shoulder. “There's nothing to be afraid of. You'll never be a stranger, if you stay here with your family and friends. As long as we climb side by side, we'll all change together.”

“Tchicaya? Can you hear me?”

It was Mariama.

“Loud and clear,” he said. “Are you all right?”

“That depends what you mean by

me

. My Qusp is fine. Parts of my Mediator got fried; I only have a short-range IR link left. My body's not a pretty sight, but it's recovering.”

The signal was coming to him via the Left Hand; she'd freed the shuttle and gone there in person. The long-range transceivers in both the module and the shuttle must have suffered irreparable radiation damage, which said something about the likely state of her body.

“What about the others?”

“Wael and Alejandro received similar exposure. They helped me get the shuttle unglued, but they weren't interested in sticking around, with no mod cons and such poor company. Birago's body seemed to be in better shape than mine, but the builders halted his Qusp, so he's as good as departed. When I left, the other rebels were all in a bad way; some of their bodies had reverted to undifferentiated goo, and even in the ones that were still intact and breathing, I'd be surprised if their minds have survived the repair process.”

She was probably right; the bodies would make liberal use of apoptosis to kill off radiation-damaged cells, and there was no reason for them to treat neural tissue any differently.

Mariama said, “I went to the Right Hand first, but it had already scribed the Planck worms. It wasn't pursuing the border down, but I gave it a nudge in the opposite direction, too fast for it to reverse. If we find some use for it, I could go and drag it back, but I'm hoping the Left Hand will be enough.”

“It will have to be.” Nothing they did to the Right Hand would render it trustworthy.

“Branco told me about the toolkit Yann gave you, while he was cutting us loose, but I didn't have time to get a copy myself. The simplest thing might be if you send it to me now, before I go chasing the border.”

“What?” Tchicaya stared at the red-shifted stars above the horizon, checking the view for any sign that he'd departed from reality and was hallucinating this entire encounter. “Why would that be simplest? You're coming to get me, aren't you?”

“That would be an awful waste of fuel. You don't need to be here, physically.”

Tchicaya was silent for a moment. She was right about the fuel, but he couldn't accept what she was proposing.

“That's not true,” he said. “If I stay out here, I'm going to lose radio contact, eventually. From sheer distance in the long run, but if the border has taken on a complicated shape, I might lose my line of sight much sooner.”

“Then give me the key to the Left Hand. With that, and the toolkit, I can manage everything.” She sighed. “Don't be precious about this. I don't like the idea of leaving you to drift away, but there are more important things at stake here. The time and the fuel I used fetching you could make all the difference to the far side.”

Tchicaya felt a flicker of temptation. He could wash his hands of everthing, and wake beside Rasmah on Pfaff. Mariama was being perfectly logical; time was against them, and apart from the secondhand skills that he could easily sign over to her, he was superfluous.

He wanted to trust her. Hadn't she earned that? They'd had no end of differences, but she had always been honest with him. It seemed petty and mean-spirited to keep on doubting her.

The trouble was, he didn't trust his own motives. Thinking the best of her would be the perfect excuse to absolve himself of all responsibility.

He said, “I'm not handing you anything. If you care so much about the far side, you'd better come and get me.”

Mariama remained seated at the front of the shuttle as Tchicaya clambered out of the airlock. He nodded a greeting, and tried to smile. Her Exoself would be discouraging her from doing anything to interfere with her body's healing, by means both gentler and more precise than a blanket of agony; extrapolating from the raw pain of the minor burns he'd willingly experienced as a child was absurd. Still, the sight of her weeping, blistered skin made his guts tighten.