Scorch Atlas

Authors: Blake Butler

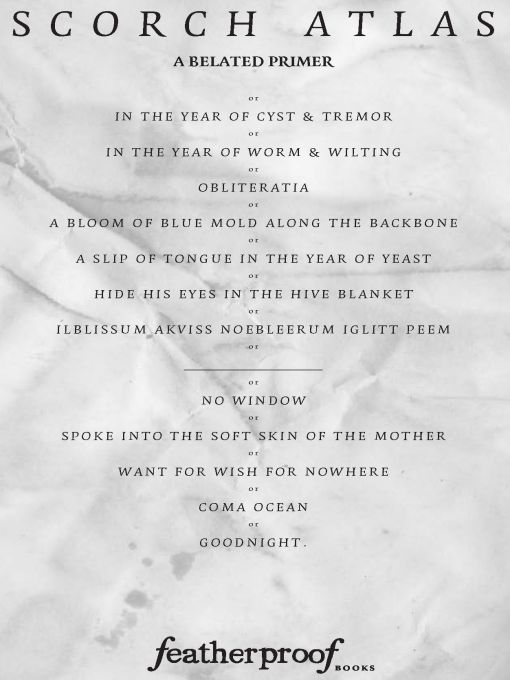

Table of Contents

Blake Butler’s

Scorch Atlas

is precisely that—a series of maps,

or worlds, “tied so tight they couldn’t crane their necks.”

Everything is either destroyed, rotting or festering—and not

only the physical objects, but allegiances, hopes, covenants.

Yet these worlds are not abstract exercises, he is speaking

of life as it is, where there might be or may be, “glass over

grave sites in display,” and where we will be forced to make

or where we have “made facemasks out of old newspapers.”

The sole glimmer of light comes in recollection, as in:

“a bear the size of several men... There in the woods

behind our house, when I was still a girl like you.”

Scorch Atlas

is precisely that—a series of maps,

or worlds, “tied so tight they couldn’t crane their necks.”

Everything is either destroyed, rotting or festering—and not

only the physical objects, but allegiances, hopes, covenants.

Yet these worlds are not abstract exercises, he is speaking

of life as it is, where there might be or may be, “glass over

grave sites in display,” and where we will be forced to make

or where we have “made facemasks out of old newspapers.”

The sole glimmer of light comes in recollection, as in:

“a bear the size of several men... There in the woods

behind our house, when I was still a girl like you.”

JESSE BALL

, author of

The Way Through Doors

and

Samedi the Deafness

KEN SPARLING

, author of

Dad Says He Saw You at the Mall

Scorch Atlas

is one of those truly original books that will make you remember where you were when you first read it.

Scorch Atlas

is relentless in its apocalyptic accumulation, the baroque language stunning in its brutality, and the result is a massive obliteration.

MICHAEL KIMBALL

, author of

Dear Everybody

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Gracious thanks to the editors of the journals in which these stories previously appeared in slightly altered forms, including:

‘The Many Forms of Rain ___ Sent Upon Us’ appeared in

DIAGRAM

’s 2008 Innovative Fiction issue. Thanks to Ander Monson.

DIAGRAM

’s 2008 Innovative Fiction issue. Thanks to Ander Monson.

‘The Disappeared’ appeared in

New Ohio Review

(/nor). Thanks to John Bullock.

New Ohio Review

(/nor). Thanks to John Bullock.

‘Smoke House’ appeared in

Hobart

. Thanks to Aaron Burch and Elizabeth Ellen.

Hobart

. Thanks to Aaron Burch and Elizabeth Ellen.

‘Gravel’ appeared in

Quick Fiction

. Thanks to Adam and Jennifer Pieroni.

Quick Fiction

. Thanks to Adam and Jennifer Pieroni.

‘Damage Claim Questionnaire’ appeared in

Lake Effect

. Thanks to George Looney.

Lake Effect

. Thanks to George Looney.

‘Want for Wish for Nowhere’ appeared in

New York Tyrant

. Thanks to GianCarlo DiTrapano.

New York Tyrant

. Thanks to GianCarlo DiTrapano.

‘Television Milk’ appeared in

The Open Face Sandwich

. Thanks to Alan Bajandas and Benjamin Solomon.

The Open Face Sandwich

. Thanks to Alan Bajandas and Benjamin Solomon.

‘The Gown from Mother’s Stomach’ appeared in

Ninth Letter

. Thanks to Jodee Stanley and Andrew Ervin.

Ninth Letter

. Thanks to Jodee Stanley and Andrew Ervin.

‘Seabed’ appeared in

Phoebe

. Thanks to Ryan Call.

Phoebe

. Thanks to Ryan Call.

‘Tour of the Drowned Neighborhood’ appeared in

Harpur Palate

. Thanks to Barrett Bowlin.

Harpur Palate

. Thanks to Barrett Bowlin.

‘The Ruined Child’ appeared in

Barrelhouse

. Thanks to Dave Housley, Matt Kirkpatrick, Mike Ingram, Joe Killiany, and Aaron Pease.

Barrelhouse

. Thanks to Dave Housley, Matt Kirkpatrick, Mike Ingram, Joe Killiany, and Aaron Pease.

‘Bath or Mud or Reclamation…’ appeared in

Avery Anthology

and in

Proximity

as a mini-book. Thanks to Andrew Palmer, Steph Fiorelli, Adam Koehler, and Mairead Case.

Avery Anthology

and in

Proximity

as a mini-book. Thanks to Andrew Palmer, Steph Fiorelli, Adam Koehler, and Mairead Case.

‘Water Damaged Photos of Our House Before I Left It’ appeared in

LIT

. Thanks to Emily Taylor.

LIT

. Thanks to Emily Taylor.

‘Exponential’ appeared in

Willow Springs

. Thanks to Sam Ligon.

Willow Springs

. Thanks to Sam Ligon.

Sections from‘Bloom Atlas’ appeared in

Ellipsis

as‘Coma Ocean’ and in

Oranges & Sardines

as‘Bloom Atlas’. Thanks to Carl Evans and Didi Menendez.

Ellipsis

as‘Coma Ocean’ and in

Oranges & Sardines

as‘Bloom Atlas’. Thanks to Carl Evans and Didi Menendez.

Caught by the rain far from shelter Macmann stopped and lay down, saying, The surface thus pressed against the ground will remain dry, whereas standing I would get uniformly wet all over, as if rain were a mere matter of drops per hour, like electricity.

MALONE DIES

THE TUNNEL

For anyone, most likely,

&

in memory of Jeff

&

in memory of Jeff

WATER

We watched our dirt go white, our crop fields blacken. Trees collapsed against the night. Insects masked our glass so thick we couldn’t see. The husks of roach and possum filled the gutters. Every inch mucked with white film. All spring the sky sat stacked with haze so high and deep it seemed a wall, a lidless cover sealing in or sealing out. Those were stretched days, croaking. I don’t know what about them broke. I don’t know why the rain came down in endless veil. It streaked the cities, wiped the wires. It splashed the dust out from our cricked knees. It came a week straight, then another. The earth turned to mud and grass to slick. Minor homes sucked underground. Children were washed out in the sloshing. The streets and theme parks bubbled brown. Some long weeks it went on that way. The air began to mush downtown. We’d just taken up wearing knee boots and canoes to market when the soft water turned to ice. Our once parched apartments saddled under gleaming. The fat white bricks pounded the face of anything uncovered. It was the last week of July. Ice dented buildings, ruined car windshields, ripped limbs clean off of trees. I saw an old man clobbered in the street, his glasses shattered, his dentures flush with blood. The backyard stacked knee-deep around me. The drum woke tones deep in my ear. I couldn’t sleep right. You never knew what might cave in. Frost killed the power, ruined the highways. Those who tried to drive were mostly mauled—run together in gagging slicks of solid liquid. Many neighborhoods froze enclosed. We spent uncounted ugly evenings with nowhere to look but at each other. When the TV finally came back, the news stations had such a backlog they began to list the names of the dead between commercials like the credits to some movie we wished we’d never seen.

THE DISAPPEARED

The year they tested us for scoliosis, I took my shirt off in front of the whole gym. Even the cheerleaders saw my bruises. I’d been scratching in my sleep. Insects were coming in through cracks we couldn’t find. There was something on the air. Noises from the attic. My skin was getting pale.

I was the first.

The several gym coaches, with their reflective scalps and high-cut shorts, crowded around me blowing whistles. They made me keep my shirt up over my head while they stood around and poked and pondered. Foul play was suspected. They sent directly for my father. They made him stand in the middle of the gym in front of everyone and shoot free-throws to prove he was a man. I didn’t have to see to know. I heard the dribble and the inhale. He couldn’t even hit the rim.

The police showed up and bent him over and led him by his face out to their car. You could hear him screaming in the lobby. He sounded like a woman.

For weeks after, I was well known. Even bookworms threw me up against the lockers, eyes gleaming. The teachers turned their backs. I swallowed several teeth. The sores kept getting worse. I was sent home and dosed with medication. I massaged cream into my wounds. I was not allowed to sleep alone. My uncle came to stay around me in the evenings. He sat in my mother’s chair and watched TV. I told him not to sit there because no one did after Mother. Any day now Dad expected her return. He wanted to keep the smell of her worn inside the cracking leather until then. My uncle did not listen. He ordered porn on my father’s cable bill. He turned the volume up and sat watching in his briefs while I stood there knowing I’d be blamed.

Those women had the mark of something brimming in them. Something ruined and old and endless, something gone.

By the third night, I couldn’t stand. I slept in fever, soaked in vision. Skin cells showered from my soft scalp. My nostrils gushed with liquid. You could see patterns in my forehead—oblong clods of fat veins, knotted, dim. I crouped and cowed and cringed among

the lack of moonlight. I felt my forehead coming off, the ooze of my blood becoming slower, full of glop. I felt surely soon I’d die and there’d be nothing left to dicker. I pulled a tapeworm from my ear.

the lack of moonlight. I felt my forehead coming off, the ooze of my blood becoming slower, full of glop. I felt surely soon I’d die and there’d be nothing left to dicker. I pulled a tapeworm from my ear.

My uncle sent for surgeons. They measured my neck and graphed my reason. Backed with their charts and smarts and tallies, they said there was nothing they could do. They retested my blood pressure and reflexes for good measure. They said say ah and stroked their chins. Then they went into the kitchen with my uncle and stood around drinking beer and cracking jokes.

The verdict on my father’s incarceration was changed from abuse to vast neglect, coupled with involuntary impending manslaughter. His sentence was increased. They showed him on the news. On screen he did not look like the man I’d spent my life in rooms nearby. He didn’t look like anyone I’d ever known.

The bugs continued to swarm my bedroom. Some had huge eyes. Some had teeth. From my sickbed I learned their patterns. They’d made tunnels through the floor. I watched them devour my winter coat. I watched them carry my drum kit off in pieces.

Another night I dreamed my mother. She had no hair. Her eyes were black. She came in through the window of my bedroom and hovered over. She kissed the crud out from my skin. Her cheeks filled with the throbbing. She filled me up with light.

The next morning my wounds had waned to splotches.

After a week, I was deemed well.

In the mirror my face looked smaller, somehow puckered, shrunken in. My eyes had changed from green to deep blue. The school required seven faxes of clearance before my readmission. Even then, no one came near me. I had to hand in my assignments laminated. I was reseated in far corners, my raised arm unacknowledged. Once I’d had the answers; now I spent the hours fingering the gum under my desk.

Other books

The Vixen and the Vet by Katy Regnery

Cloaked by Alex Flinn

A Dangerous Masquerade by Linda Sole

Doctor's Orders by Daniella Divine

Undertow by Leigh Talbert Moore

The Ultimate Guide to Kink by Tristan Taormino

Learning to Swim by Cosby, Annie

Rumors by Katy Grant

The Journey by John Marsden