Sea of Ink (4 page)

Authors: Richard Weihe

Tags: #German, #Biographical, #China, #Historical, #Fiction

17

Geshan wandered across the rocky heath near to the monastery and thought about the things the master had told him.

Once back in his room he sat at the desk by the window and stared at the mountain on the horizon.

He rubbed the ink he usually worked with, the ink which he had saved from his father’s workshop. The balls from Pan Gu were in a safe place.

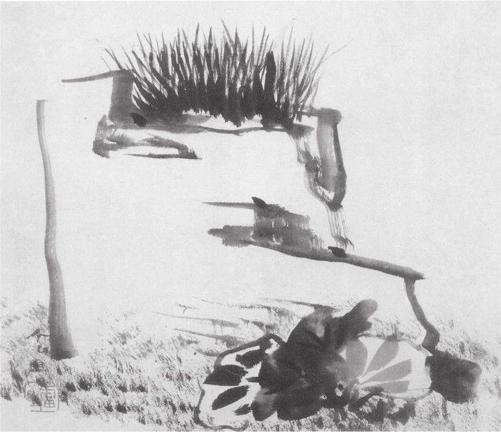

He covered the small piece of paper he had laid out with a few rapidly executed vertical and horizontal strokes. In the right half of the picture he interrupted a downwards sweep by lifting the brush and, from the centre of the paper, painted a broad line which he guided along a gentle incline to the right-hand edge of the paper, then made a straight brushstroke from the end of this down to the bottom with a single fluid movement of the hand.

With irregular strokes he drew two round shapes at the bottom of the paper and between these applied his brush a dozen times to form triangular patches of ink. Several times he covered the same small section of the paper with these softly contoured triangles to produce a many-layered area of ink in a variety of shades of black.

He enveloped the round shapes by dashing the tip of the brush rhythmically across the entire width of the paper to leave fine marks. Finally, in a gentle wave-like movement, he added a few longer, diagonal strokes above the round shapes, running from left to right. But at the very top, to one of the detached horizontal lines that stretched almost a third of the way across, he added a dense cluster of rough, spiky strokes; and directly beneath the horizontal line, set in the corner, he drew an elongated rectangle until his paintbrush had released its last drop of ink.

He dipped it in briefly a second time, just the tips of the bristles, to sign his picture with a new name. He wrote: ‘Renwu’ – human space.

He printed his seal in the corner.

The ink was soon dry. He attached the picture to the wall to view it from a distance.

Now he could see two stones on coarse grass, nestling up to a larger boulder. In their shelter grew a modest mountain flower with many leaves, watched over by the rough-edged rock. It gazed proudly and rebelliously through its eye slits and its hair spiked upwards like the spines of a hedgehog preparing to defend itself.

Renwu recognized himself not in the boulder, but in the tiny plant. The fortune to be oneself was sufficient for the plant to sit at the centre of the world.

Calamus

18

In the temple at the Monastery of the Green Cloud, Geshan, who now called himself Renwu, learnt of the death of his wife and son.

He had almost forgotten his time as Zhu Da, as a prince and husband and father.

Now the memories of the past stabbed him like knives.

From that day he let his hair grow again.

He went into town more frequently. He scanned the facial features of the women for a lost expression, a smile that no longer existed.

He recalled once more the moment when the court announced that they had found a suitable woman for him and that the marriage had been arranged.

‘You will marry and have children, for whoever breaks the ancestral chain forsakes the very thing by which he became a descendant.’

Did he have to fear once more that he would remain without descendants?

He wanted to obey Confucian law and continue his line.

So now he entertained the idea of starting a family again.

19

He went to his pupils and told them he would be leaving the monastery.

After appointing his successor he removed his priestly robe and burnt it.

He tied together his picture album, packed away his collection of paintbrushes and ink and went down into the valley.

He looked back at the mountain and the Monastery of the Green Cloud. He had spent twenty years there, reconstructing the building and introducing his own strict rules. More than one hundred monks had been instructed by him.

The year was 1680 and now, over fifty years old, he wanted to reconnect with the past. He thought of the old saying: Falling leaves return to their roots.

But what was he now? Where was home to him? What was his name? He needed to find answers to everything.

He had placed all his pictures and painting things in a few sandalwood boxes which his pupils had given him as a leaving present. Inside he found pieces of paper on which each of the pupils had written some farewell words. They moved him greatly.

As he was crossing a river one evening he was set upon by highwaymen. Because the boxes were heavy, the

highwaymen

may have thought that they contained jade and gold. They stole the whole lot without opening them.

This incident troubled him for many weeks and during this time he kept his distance from other people,

speaking

to nobody.

He strove to recall his pupils’ words from memory, to write down everything and thereby recover his lost treasure piece by piece. The only possessions that remained were a brush and Pan Gu’s balls of ink, for he always carried these next to his body.

And not a single day passed when he did not paint or fill paper with calligraphy. Now, however, he merely signed his pictures with the character

lü

. Lü meant ass.

Bald ass

was a nickname for monks.

20

In the same year that he returned to

Nanchang

he married for a second time. She was a beautiful woman from a modest

background

to whom he did not disclose his true origins.

As a wedding present he gave her a fan which he had painted. On the fan was a large, round moon, beside it a branch with a single blossom and beneath were the words:

Words spoken by kindred souls have the fragrance of orchids.

That same day he painted another picture in his album. Below it he wrote the lines:

Above Nanchang in the middle of autumn the moon stands alone. At midnight smoke rises from the censer in the form of a dragon. The dream vanishes in a dark cloud. The

beautiful

lady wears a long silk ribbon. The wind blows, but cannot catch it.

He signed this picture with yet another new name which now he used alongside Lü: Poyun Qiaozhe – woodcutter of the evaporated clouds.

But he and his young bride did not find happiness together. He felt as if he were floating in a dark cloud, and what he could see through it seemed dismal and unreal. He remained restless.

He placed a card on his desk as a reminder and a warning. On it were the words:

Life and death matter.

21

Acquaintances old and new tried to win him for their artistic circles. They organized

poetry

and music evenings in the hope that he would come.

Such events had become especially popular with the new ruling magistrates. And so one day Poyun Qiaozhe was invited by the venerable magistrate Hu Yitang to a poetry banquet, an invitation which would have required great diplomatic skill to decline. So he went along.

The host had hung every wall with empty sheets of paper. When all had assembled and plenty of wine had been passed round, he had one of his guests blindfolded: a young painter. The painter was taken from wall to wall and challenged to paint characters – made-up ones, but different each time. And each time the guests had to invent a name for the shape created by his brushstrokes. They came up with ideas such as

lotus leaf, death head, raindrop and broken jade clasp

. Or more fancy ones such as

dragon’s head, silk thread, bundles of kindling, contorted cloud

and

untied rope.

When a name had been agreed, it was written beneath the character. At night, in the darkness, the names were called out once more. Now the guests had to describe from memory the character associated with a

particular

name.

Lü, or Poyun Qiaozhe, as Zhu Da now called himself, tried to recreate the painter’s brushstrokes with words as he fashioned the shape they had entitled

folded medal ribbon

. When the servant with the oil lamp then lit up the relevant character on the wall, everyone thought that Poyun had actually used his words as a brush, so precisely had the woodcutter of the evaporated clouds described the medal ribbon.

22

Poyun Qiaozhe was visited by one of his former pupils. The latter told him that old Abbot Hongmin was terminally ill and had called for him. They set off for the mountains together and found the master on his deathbed, in a temple outside the monastery complex.

‘All I live on now is ginseng and other medicinal plants, but these do not help; it is too late. My body is a barren tree which waits for the crows of winter and will not see another summer. I am delighted that you have come. You are seeing me for the last time in this life.’

The old man pointed to a box by the wall.

‘I am bequeathing you my paintbrushes. They must stay in motion. I know that you will use them wisely. You will not let them lie idle; you will capture on paper the mountains and lakes that you come across and you will not waste your time.’

It was spring and the door to the veranda had been pushed open, offering a view of the landscape bathed in a soft light.

‘When you have my brushes in your hand, then remember my words,’ the master said. ‘The water that flows between the mountains and the sea will teach you all that you need to know to understand the world. It has the rare quality of being able to benefit all beings without dispute. Knowing the functions of the

mountain

without knowing the functions of the water is like the man who sinks into the sea without knowing its beaches or who stands on the beach without knowing the immense spaces which fill the sea.’

The master paused. Finally he said, ‘Ink is water rendered visible, nothing more. The brush divides what is fluid from everything superfluous.’

23

When the dynasties changed in 1644, the Shunzhi emperor, then a boy, was set on the Dragon Throne. He favoured Chinese officials and placed particular trust in the advice of the eunuchs. His defeat of the rebellion led by General Wu was an

important

step towards consolidating Manchu rule. When he died in 1661, still a young man, he was succeeded by his eight-year-old son, Kangxi.

Kangxi was greatly interested in classical Chinese

culture

and supported everything which helped to preserve tradition. Wherever possible he sought to cooperate with the native upper class and benefit from their knowledge.

After the master’s death, Poyun avoided all occasions that he suspected had been organized by the new

administration

. One day, however, he received a request from the highest office of imperial government to take part, alongside the noble men of letters of the old regime, in a specially arranged examination officially designated as an ‘Investigation into Great Scholarship’. The new rulers wished to write the history of their empire and for this they needed experts on previous eras.

Poyun was unable to dodge this summons. And so he sat the examination with a large number of

hand-picked

scholars.

Months later, when the results were assessed, he received an official invitation to place his knowledge as a historian of the Ming period at the disposal of the new rulers. The magistrate Hu Yitang invited him to spend a year in his residence, where, free of all worries, he would be able to devote himself to his art, on the condition that he collaborated in the great history project.

Poyun understood at once that this was not an

invitation

, but a veiled command which he must obey.

But he refused to serve the authorities. Instead he threw himself on the ground, yelling and howling; or he roamed through the town laughing, and talked to the swallows. He sat down right in the middle of the town square. Now he was drumming on his belly and singing rude songs; now he was dashing in a fury through the market stalls, hurling vegetables into the air.

The official responsible reported to the

commission

that Poyun had gone mad and so could not be recommended for working on the history of the former dynasty.

‘He’s mad? So why do the creations of his paintbrush have such immediacy and power?’ the official was asked. ‘And for what reason did the commission put him into the highest category of scholarship, the

Sea of Ink

?’

‘What can I say?’ the official replied. ‘These are the creations of a madman. Should we wish to have the history of the empire written by a madman?’

Observing the willingness with which former Chinese officials and tutors agreed to collaborate on the

historical

work filled Poyun with disgust and bitter sarcasm.

They had been offered the bait and taken it.

But able to see the hook in the bait, he had held himself back and continued to swim in the sea of ink.