Sea of Ink (5 page)

Authors: Richard Weihe

Tags: #German, #Biographical, #China, #Historical, #Fiction

24

Sometimes a tightness gripped his chest. He felt both exuberant and deeply saddened, like a surging spring hemmed in by a rock, or a fire smothered by a wet blanket.

He had a dream.

He was lying on the petal of a giant lotus flower, a satiny, unshaded, fragrant surface. All at once this white carpet began to draw up at the edges until it formed a funnel. His body toppled and started rolling. As the petal goblet became steeper there was nothing he could hold on to, and he began to slip until he fell into a bowl. It was filled with black ink. The ink was warm, like his body, and he was not afraid, he felt secure in there. Now he dived into the dark liquid, closing his eyes and mouth. He did not gasp for air; the ink seemed to breathe for him.

It sucked him in, through a long, narrow channel only as wide as his body. Inside the flower stem he slid down until at some point he felt a soft pad absorb the ink like sand does water. It became ever brighter until he could make out a silver strip of light in the distance. Carried on a gentle black wave, he approached the light. He stroked his hand over the ground and felt the rough surface of paper.

Now he felt his body, too: he was wet and smooth. His skin had become scaly with a red shimmer. He tried to stand but his legs were missing. He had grown fins in their place and they stuck to the paper. He struggled to free them, but the struggling only stuck them more firmly to the paper.

He called out to a man who was walking past, ‘I’ve become separated from my natural surroundings, I’m helpless. If I could just have a bucket of water, that would keep me alive!’

The man bent down towards him. He recognized the face of the government commissar who had brought him the imperial assignment to work on the great history. The man stroked his smooth belly to check how wet it was and then said, ‘I’m on my way to the ink sea. I’m going to run a channel from there to here. So you’ll be able to swim over. Is that all right with you, goldfish?’

‘If you have your way, sir, you’ll soon be finding me in the shop that sells dried fish!’

25

He and his wife became estranged. She found his mood swings and taciturnity intolerable, and went back to her family. He himself was in despair about his condition and he begged her not to spurn him. He lambasted her: ‘You made a show of insisting how we should eat and sleep

together

. But over the past thirty days there have been twenty-nine when we have not. Every night leaves fall from the wutong tree and the seeds become

increasingly

meagre.’

She asked him why he danced and sobbed outside, and sometimes behaved skittishly only to fall back into silence again. Why was he away so often?

Suddenly she was afraid of him.

He painted a small picture of crab-apple blossom and wrote beneath it:

Your husband is just as good and bad as before. Why is there no harmony between you and him any longer? Why do you make plans to exchange him for a horse? Once we spoke of buying a pine wood on the other side of the Wu bridge and raising deer and making the best ink for all the world’s pictures. Red flowers carpet the hillside, the spring streams caress the rocks. Like your love they open their flowers and then wither. The stream flows endlessly, like my sorrow.

He sent her this picture after she had already left him. But she did not reply. He wrote to her once more:

On whom should the scent of the orchid model itself? I can no longer tell whether twilight belongs to the morning or the evening. Was it you who sent me these cawing ravens? I hate the pasture by the pavilion. I watch ants

in the moss moving their nest. The sadness of the pines dripping in the rain and this wind which never stops blowing.

But no word ever came back.

26

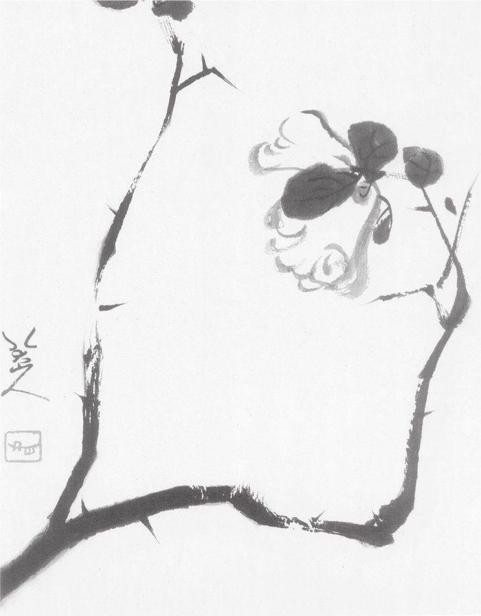

It was at this time that he first summoned the courage to hold his dead master’s paintbrush. He set out a piece of paper and poured water into the hollow of the rubbing stone. He rubbed the ink and drenched the brush. Then he ran it over the peach stone until the bristles stopped dripping.

Starting in the bottom left-hand corner, he made a bold stroke across the entire width of the paper and then continued in a right angle upwards, slowly lifting his hand so that the line, after a slight curve to the left, finished in a point. Around this point he planted three deep-black, almost round blobs, inserting between these some

delicate

, parallel, wavy lines with the tip of the brush.

Above where the thick line at the bottom began, he now led the brush in a gently winding movement to the top, where he again finished the stroke with two blobs cut off by the edge of the paper. He added a few short spikes on either side of the three bold strokes by

thrusting

the tip of the brush into the black vein from about a finger’s width away.

He wet the brush tip with ink a second time and signed the small piece of paper with the characters

ba da shan ren

. He had given himself another name: man on the mountain of the eight compass points.

He endorsed the picture with his seal.

When he fixed the picture to the wall to view it, he could see a fine forked branch at the end of which sat a rose in bloom.

Like an armed guard, the thorny branch defended the beauty at its tip. The seductive petals would soon fall, but the thorns would remain.

Branch of blossom with thorns

27

Since his second wife had left him, Bada Shanren had been leading the life of a

vagabond

. At the age of sixty he no longer had his own retreat; he was free from all ties.

He had renounced whatever would not fit into his paltry luggage. Everything else seemed superfluous.

Like a bird he drifted from place to place, whistling and singing, only ever settling down temporarily. He accepted all the hospitality extended to him. But often people were full of mistrust when they met him; they thought he was mad.

Wherever possible he stayed with friends.

When he met an old acquaintance he would make himself useful straight away and work for him all day long without a break. He pushed himself to the limit, forgetting all else as he did so.

This was how he lived.

28

From this time he used only the one name, Bada Shanren. He was asked about the meaning of the name and he would reply, ‘The points of the compass symbolize the eight directions of space which each painter worthy of the title must be capable of opening up with a single brushstroke.’

Whenever he wrote the four characters of his name,

ba da shan ren

, he would put them together in such a way that they could be read not only as Bada Shanren, but also in another arrangement: as the characters

kuzhi

and

xiaozhi

, which mean the crying man and laughing man. He was the laughing man who also cried, and the crying man who laughed too. He could not merely cry or laugh; his laughter always contained a tear and he cried tears of laughter.

‘Isn’t it terrible to live with so much uncertainty and fear for the future?’ he was asked by a friend who put him up for a while.

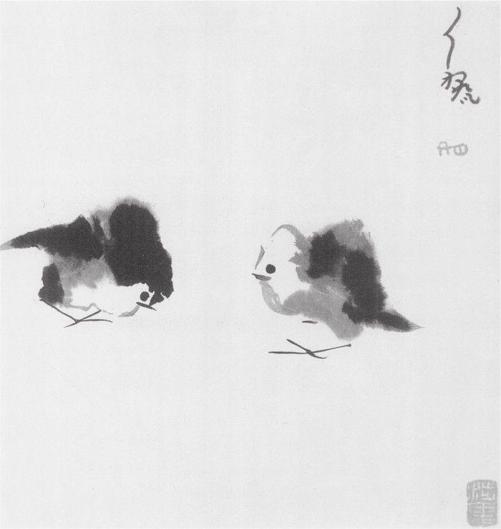

That same night Bada Shanren took out a piece of paper, rubbed some ink and lowered his brush into the hollow of the rubbing stone.

He painted a large dot somewhat to the right of the centre of the paper. Below this a short, flat line, to the side of that a similar vertical one, and above the dot a finely drawn arc the breadth of a fingertip. He left some space around these marks, then he painted a palm-sized area beside and below the two short lines by pressing the brush down onto the paper, rolling it on its axis and wiggling it to produce an irregular black patch whose edges, punctuated by individual bristles, had extremely fine points.

At the bottom of this ball of colour he drew a thin, horizontal line which extended as far as the vertical axis of the dot. Halfway along this line he added a second, equally thin but much shorter line, crossing the first one at a sharp angle.

In the left half of the picture, a little lower than the first dot, he now painted a second one which he likewise bordered with a line that he brought downwards in a gentle arc and then took to the right, almost

horizontally

. Where the line ended he applied the brush to the paper once more, leading it downwards diagonally and then, with a tilt of his hand, angling it slightly to the right. Through the resulting bend he painted a straight line downwards, bringing it to a point shortly after the intersection. Above the second dot he pressed the brush down onto the paper as before, extending the blotch that appeared upwards, eventually letting it fade to the side. An almost rectangular shape emerged above the dot, forming a slight overhang in the upper right corner.

Now he dipped his brush again and signed the paper with the characters

ba da shan ren

. Finally he printed his red seal on it. He presented the picture to his host, saying, ‘Here you can see how I feel.’

‘But that’s two chicks,’ his host said.

‘Yes,’ Bada replied, ‘and there’s an eagle circling above them, but that you can see only in the chicks’

expressions

. The bird of prey will swoop down on top of them, but they can share their fear and rely on their mother. I crossed the threshold and left my homeland long ago, and my heart trembles along the length of the path. I share my fear with my pictures alone.’

Two chicks

29

One day Bada Shanren was the guest of a goldfish breeder. He showed Bada around his garden, which he called the Garden of the Yellow Bamboo.

To Bada’s great astonishment, his host did not

mention

goldfish once. He had made up his own lyrical names for all the shrubs and trees, and he enthused about their subtle colours and the variety of their leaf forms. Late in the afternoon he suddenly grabbed Bada’s arm.

‘This is the moment. Now the light is perfect.’

Bada was taken to the veranda behind the house. There, an assistant was standing a number of blue-

and-white

porcelain bowls on the low wall.

‘Master,’ the host said, ‘please look at my fish. Look at them all and tell me which colour you like best!’

Bada looked one by one into all the bowls. He noticed that the goldfish breeder had arranged the fish in a colour scale. The first one was saffron yellow. The scales of the second glistened pink, the third and fourth were both bright orange. The fifth shone a lurid red, the sixth had a purple back. The final one seemed to him almost violet.

In each bowl was a single fish, almost the size of carp. They were so large that they could swim only in a tight circle, forced to bend their heavy bodies to the limit. It was clear that they noticed the change in light on the water when Bada bent over them. They looked at him through the clear water with their large round eyes and seemed to be trying to kiss the surface with their plump lips, shattering the delicate glass each time. The light glinted colourfully on their stout backs.

Bada chose the last fish, the violet one.

‘Why the darkest one, Master?’ the goldfish breeder asked with a hint of surprise.

‘If I stood by the pond in the noonday sunlight and saw a school of your violet fish, I would be watching the night swimming in the water.’

30

After his visit to the goldfish breeder, Bada Shanren settled on the shore of a lake near the Orchid Temple and put himself up in an old fisherman’s hut. He gave his modest abode the name Song after Waking, which he wrote on the wooden planks in large white characters.

When he had become familiar with his surroundings and had found peace again, he put a long roll of paper on his low painting table. To keep the paper flat he weighed it down with stones from the river. He rubbed ink and dipped his paintbrush.

In the upper left-hand corner of the picture he allowed a large, irregular shape to emerge, which in places he outlined with shading. Diagonally opposite, in the lower right-hand corner of the picture, he painted a second shape, similar to the first. Their contours seemed to snuggle up to each other across the wide space between. In this empty space Bada used the tip of his brush to paint a tiny arc, the upper end of which split into two prongs. Two hand widths away from this, set slightly below, he made a stroke across the paper which also divided on the right, but which was then rounded off by another delicate downwards stroke, thereby leaving a narrow empty space between the upper straight line and lower rounded one.

He painted four other objects of a similar shape and size, close to the outline of the large shape at the bottom.

To finish he signed his name, stamping his seal below it.

When the ink was dry he attached the roll of paper to one of the ceiling beams so that it caught the light shining in. Here the black colour swallowed the sun’s rays; there the ink let the light filter through and grey clouds appeared, while in the backlight the unpainted area of the paper acquired the depth of sand dunes.

Two boulders jutted out of the embankment above the still water of the lake. There was movement between the rocks and around them. Minnows darted about in the clear water.

A gentle gust of wind caught the picture hanging like a curtain and a faint tremor ran in a wave down the length of the paper. For a few moments the little fish took off and swam in the air. Their joy was for the eternity that lay before them. But no one was pressing them to express it openly.