Sex at Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality (26 page)

Read Sex at Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality Online

Authors: Christopher Ryan,Cacilda Jethá

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social Science; Science; Psychology & Psychiatry, #History

Approximately eight hundred skeletons from the Dickson Mounds in the lower Illinois Valley have been analyzed. They reveal a clear picture of the health changes that accompanied the shift from foraging to corn farming around 1200 AD.

Archaeologist George Armelagos and his colleagues reported that the farmers’ remains show a 50 percent increase in chronic malnutrition, and three times the incidence of infectious diseases (indicated by bone lesions) compared with the foragers who preceded them. Furthermore, they found evidence of increased infant mortality, delayed skeletal growth in adults, and a fourfold increase in porotic hyperostosis, indicating iron-deficiency anemia in more than half the population.11

Many have noted the strangely cavalier approach to food among foragers, who have nothing in the freezer. French Jesuit missionary Paul Le Jeune, who spent some six months among the Montagnais in present-day Quebec, was exasperated by the natives’ generosity. “If my host took two, three, or four Beavers,” wrote Le Jeune, “whether it was day or night, they had a feast for all neighboring Savages. And if those people had captured something, they had one also at the same time; so that, on emerging from one feast, you went to another, and sometimes even to a third and a fourth.” When Le Jeune tried to explain the advantages of saving some of their food, “They laughed at me. ‘Tomorrow’ (they said) ‘we shall make another feast with what we shall capture.’ “12

Israeli anthropologist Nurit Bird-David explains, “Just as Westerners’ behaviour is understandable in relation to their assumption of

shortage,

so hunter-gatherers’ behaviour is understandable in relation to their

assumption of affluence.

Moreover, just as we analyze, even predict, Westerners’

behavior by presuming that they behave as if they did not have

enough,

so

we

can

analyze,

even

predict,

hunter-gatherers’ behaviour by presuming that they behave as if they had it made [emphasis added].”13

While farmers toil to grow rice, potatoes, wheat, or corn, a forager’s diet is characterized by a variety of nutritious plants and critters. But how much work is foraging? Is it an efficient way to get a meal?

Archaeologist David Madsen investigated the energy efficiency of foraging for Mormon crickets

(Anabrus

simplex),

which had been on the menu of the local native people in present-day Utah. His group collected crickets at a rate of about eighteen crunchy pounds per hour. At that rate, Madsen calculated that

in just an hour’s work,

a forager could collect the caloric equivalent of eighty-seven chili dogs, forty-nine slices of pizza, or forty-three Big Macs—without all the heart-clogging fats and additives.14 Before you scoff at the culinary appeal of Mormon crickets, give some thought to the frightening reality lurking within a typical chili dog.

Another study found that the !Kung San (in the Kalahari desert, mind you) had an average daily intake (in a good month) of 2,140 calories and ninety-three grams of protein.

Marvin Harris puts it simply: “Stone age populations lived healthier lives than did most of the people who came immediately after them.”15

And maybe healthier than people who came

long

after them, too. The castles and museums of Europe are full of suits of armor too small to fit any but the most diminutive of modern men. While our medieval ancestors were shrimpy by modern standards, archaeologist Timothy Taylor believes that the human ancestors who first controlled fire—about 1.4 million years ago—were taller than the average person today.

Skeletons dug up in Greece and Turkey show that pre-agricultural men in those areas were about five foot nine on average, with women being about five foot five. But with the adoption of agriculture, average height plummeted.

Modern Greeks and Turks still aren’t as tall, on average, as their ancient ancestors.

Throughout the world, the shift to agriculture accompanied a dramatic drop in the quality of most people’s diets and overall health. Describing what he terms “the worst mistake in human history,” Jared Diamond writes, “Hunter-gatherers practiced the most successful and longest-lasting life style in human history. In contrast,” he concludes, “we’re still struggling with the mess into which agriculture has tumbled us, and it’s unclear whether we can solve it.”

On Paleolithic Politics

Prehistoric life involved a lot of napping. In his provocative essay “The Original Affluent Society,” Sahlins notes that among foraging people, “the food quest is so successful that half the time the people do not seem to know what to do with themselves.”16 Even Australian Aborigines living in apparently unforgiving and empty country had no trouble finding enough to eat (as well as sleeping about three hours per afternoon in addition to a full night’s rest). Richard Lee’s research with !Kung San bushmen of the Kalahari Desert in Botswana indicates that they spend only about fifteen hours per week getting food. “A woman gathers on one day enough food to feed her family for three days, and spends the rest of her time resting in camp, doing embroidery, visiting other camps, or entertaining visitors from other camps. For each day at home, kitchen routines, such as cooking, nut cracking, collecting firewood, and fetching water, occupy one to three hours of her time. This rhythm of steady work and steady leisure is maintained throughout the year.”17

A day or two of light work followed by a day or two off.

How’s that sound?

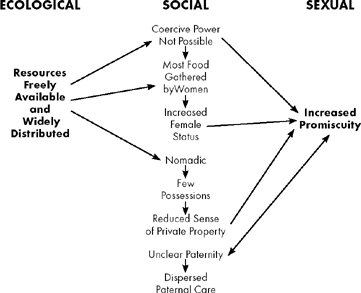

Because food is found in the surrounding environment, no one can control another’s access to life’s necessities in hunter-gatherer society. Harris explains that in this context,

“Egalitarianism is … firmly rooted in the openness of resources, the simplicity of the tools of production, the lack of non-transportable property, and the labile structure of the band.”18

When you can’t block people’s access to food and shelter, and you can’t stop them from leaving, how can you control them? The ubiquitous political egalitarianism of foraging people is rooted in this simple reality. Having no coercive power,

leaders

are

simply

those

who

are

followed—individuals who have earned the respect of their companions. Such “leaders” do not—cannot—

demand

anyone’s obedience. This insight is not breaking news. In his

Lectures

on

Jurisprudence,

which

was

published

posthumously in 1896, Adam Smith wrote, “In a nation of hunters there is properly no government at all…. [They] have agreed among themselves to keep together for their mutual safety, but they have no authority one over another.” It’s

not

surprising

that

conservative

evolutionary

psychologists have found foragers’ insistence on sharing to be one of their most difficult nuts to crack. Given the iconic status of Dawkins’s book

The Selfish Gene

and the popularized, status-quo protective notion of the all-against-all struggle for survival, the quest to explain why foraging people are so maddeningly generous to one another has occupied dozens of authors. In

The Origins of Virtue,

science writer Matt Ridley summarizes the inherent contradiction they face:

“Our minds have been built by selfish genes, but they have been built to be social, trustworthy and cooperative.”19 One must walk a tightrope to insist that selfishness is (and has always been) the principal engine of human evolution even in the face of copious data demonstrating that human social organization was founded upon an impulse for sharing for many millennia.

Of course, this conflict would evaporate if proponents of the

always-selfish

theory of human nature accepted contextual limits to their argument. In other words, in a zero-sum context (like that of modern capitalist societies where we live among strangers), it makes sense, on some levels, for individuals to look out for themselves. But in other contexts human behavior is characterized by an equal instinct toward generosity and justice.20

Even if many of his followers prefer to ignore the subtleties of his arguments, Dawkins himself appreciates them fully, writing, “Much of animal nature is indeed altruistic, cooperative and even attended by benevolent subjective emotions…. Altruism at the level of the individual organism can be a means by which the underlying genes maximize their self-interest.”21 Despite famously inventing the concept of the

“selfish gene,” Dawkins sees group cooperation as a way to advance an individual’s agenda (thereby advancing each individual’s genetic interests). Why, then, are so many of his admirers unwilling to entertain the notion that cooperation among human beings and other animals may be every bit as

natural

and effective as short-sighted selfishness?

Nonhuman primates offer intriguing evidence of the “soft power of peace”—and not just horny bonobos, either. Frans de Waal and Denise Johanowicz devised an experiment to see what would happen when two different macaque species were placed together for five months. Rhesus monkeys

(Macaca

mulatta)

are aggressive and violent, while stump-tails

(Macaca arctoides)

are known for their more chilled-out approach to life. The stump-tails, for example, make up after conflict by gripping each other’s hips, whereas reconciliations are rarely witnessed among rhesus monkeys. Once the two species were placed together, however, the scientists saw that the more peaceful, conciliatory behavior of the stump-tails dominated the more aggressive rhesus attitudes. Gradually, the rhesus monkeys relaxed. As de Waal recounts, “Juveniles of the two species played together, groomed together, and slept in large, mixed huddles. Most importantly, the rhesus monkeys developed peacemaking skills on a par with those of their more tolerant group mates.” Even when the experiment concluded, and the two species were once again housed only with their own kind, the rhesus monkeys were still three times more likely to reconcile after conflict and groom their rivals.22

A fluke? Neuroscientist/primatologist Robert Sapolsky has spent decades observing a group of baboons in Kenya, starting when he was a student in 1978. In the mid-1980s, a significant proportion of adult males in the group abruptly died of tuberculosis they’d picked up from infected food in a dump outside a tourist hotel. But the prized (albeit infected) dump food had been eaten only by the most belligerent baboons, who had driven away less aggressive males, females, or juveniles. Justice! With all the hard-ass males gone, the laid-back survivors were in charge. The defenseless troop was a treasure ready-made for pirates: a whole troop of females, sub-adults, and easily cowed males just waiting for some neighboring tough guys to waltz in and start raping and pillaging.

Because male baboons leave their natal troop at adolescence, within a decade of the dump cataclysm, none of the original, atypically mellow males were still around. But, as Sapolsky reports, “the troop’s unique culture was being adopted by new males joining the troop.” In 2004, Sapolsky reported that two decades after the tuberculosis “tragedy,” the troop still showed higher-than-normal rates of males grooming and

affiliating with females, an unusually relaxed dominance hierarchy, and physiological evidence of lower-than-normal anxiety levels among the normally stressed-out low-ranking males. Even more recently, Sapolsky told us that as of his most recent visit, in the summer of 2007, the troop’s unique culture appeared to be intact.23

In

Hierarchy in the Forest,

primatologist Christopher Boehm argues that egalitarianism is an eminently rational, even hierarchical political system, writing, “Individuals who otherwise would be subordinated are clever enough to form a large and united political coalition, and they do so for the express purpose of keeping the strong from dominating the weak.” According to Boehm, foragers are downright feline in refusing to follow orders, writing, “Nomadic foragers are universally—and all but obsessively—concerned with being free of the authority of others.”24

Prehistory must have been a frustrating time for megalomaniacs. “An individual endowed with the passion for control,” writes psychologist Erich Fromm, “would have been a social failure and without influence.”25

What if—thanks to the combined effects of very low population density, a highly omnivorous digestive system, our uniquely elevated social intelligence, institutionalized sharing of food, casually promiscuous sexuality leading to generalized child care, and group defense—human prehistory was in fact a time of relative peace and prosperity? If not a

“Golden Age,” then at least a “Silver Age” (“Bronze Age” being taken)? Without falling into dreamy visions of paradise,