Sex at Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality (27 page)

Read Sex at Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality Online

Authors: Christopher Ryan,Cacilda Jethá

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social Science; Science; Psychology & Psychiatry, #History

can we—dare we—consider the possibility that our ancestors lived in a world where for most people, on most days, there was enough for everyone? By now, everyone knows “there’s no free lunch.” But what would it mean if our species evolved in a world where

every

lunch was free? How would our appreciation of prehistory (and consequently, of ourselves) change if we saw that our journey began in leisure and plenty, only veering into misery, scarcity, and ruthless competition a hundred centuries ago?

Difficult as it may be for some to accept, skeletal evidence clearly shows that our ancestors didn’t experience widespread, chronic scarcity until the advent of agriculture.

Chronic food shortages and scarcity-based economies are artifacts of social systems that arose with farming. In his introduction to

Limited Wants, Unlimited Means,

Gowdy points to the central irony: “Hunter-gatherers … spent their abundant

leisure

time

eating,

drinking,

playing,

socializing—in short, doing the very things we associate with affluence.”

Despite no solid evidence to support it, the public hears little to dispute this apocalyptic vision of prehistory. The sense of human nature intrinsic to Western economic theory is mistaken. The notion that humans are driven only by self-interest is, in Gowdy’s words, “a microscopically small minority view among the tens of thousands of cultures that have existed since

Homo sapiens

emerged some 200,000

years ago.” For the vast majority of human generations that have ever lived, it would have been unthinkable to hoard food when those around you were hungry. “The hunter-gatherer,” writes Gowdy, “represents

uneconomic

man.”26

Remember, even those “wretched” inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego, condemned to “the bottom of the scale of human beings,” threw down their hoes and walked away from their gardens once the HMS

Beagle

sailed out of sight. They knew firsthand how “civilized” people lived, yet they had “not the least wish to return to England.” Why would they? They were

“happy and contented” with “plenty fruits,” “plenty fish,” and

“plenty birdies.”

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

The

Never-Ending

Battle

over

Prehistoric

War

(Brutish?)

Evolutionists say that back in the twilight of life a beast, name

and nature unknown, planted a murderous seed and that the

impulse thus originated in that seed throbs forever in the

blood of the brute’s descendants….

WILLIAM JENNINGS BRYAN1

Just as neo-Hobbesian fundamentalists hold that poverty is intrinsic to the eternal human condition, they maintain that war is fundamental to our nature. Author Nicolas Wade, for example, claims that “warfare between pre-state societies was incessant, merciless and conducted with the general purpose, often achieved, of annihilating the opponent.”2 According to this view, our propensity for organized conflict has roots reaching deep into our biological past, back to distant primate ancestors by way of our foraging forebears. It’s

always

been about making war, supposedly, not love.

But nobody’s very clear what all this incessant war was over.

Despite his certainty that foragers’ lives were plagued by

“constant warfare,” Wade acknowledges that “ancestral people lived in small egalitarian societies, without property, or leaders or differences of rank….” So we’re to understand that egalitarian, nonhierarchical, nomadic groups without property … were constantly at war? Hunter-gatherer societies, possessing so little and thus with so little to lose (other than their lives), living on a wide-open planet were nothing like the densely populated, settled societies struggling over dwindling or accumulated resources in more recent historical times.3 Why would they be?

We’ve no space for a comprehensive response to this aspect of the standard Hobbesian narrative, but we’ve selected three well-known figures associated with it for a closer look at their arguments and data: evolutionary psychologist Stephen Pinker, the revered primatologist Jane Goodall, and the world’s most famous living anthropologist, Napoleon Chagnon.4

Professor Pinker, Red in Tooth and

Claw

Imagine a high-profile expert stands before a distinguished audience and argues that Asians are warlike people. In support of his argument, he presents statistics from seven countries: Argentina, Poland, Ireland, Nigeria, Canada, Italy, and Russia. “Wait a minute,” you might say, “those aren’t even Asian countries—except, possibly, Russia.” The expert would be laughed off the stage—as he should be.

In 2007, world-famous Harvard professor and best-selling author Steven Pinker gave a presentation built upon similarly flawed logic at the TED conference (Technology, Entertainment, Design) in Long Beach, California.5 Pinker’s presentation provides both a concise statement of the neo-Hobbesian view of the origins of war and an illuminating look at the dubious rhetorical tactics often used to promote this bloodstained vision of our prehistory. The twenty-minute talk is available at the TED website.6 We encourage you to watch at least the first five minutes (dealing with prehistory) before reading the following discussion. Go ahead. We’ll wait here.

Though Pinker spends less than 10 percent of his time discussing hunter-gatherers (a social configuration, you’ll recall, that represents well over 95 percent of our time on the planet), he manages to make a real mess of things.

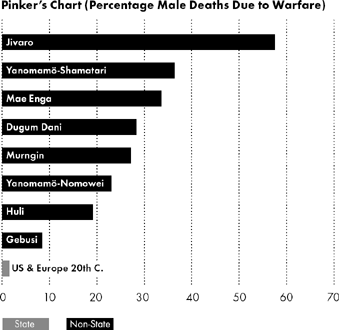

Three and a half minutes into his talk, Pinker presents a chart based on Lawrence Keeley’s

War Before Civilization: The

Myth of the Peaceful Savage.

The chart shows “the percentage of male deaths due to warfare in a number of foraging or hunting and gathering societies.” He explains that the chart shows that hunter-gatherer males were far more likely to die in war than are men living today.

But hold on. Take a closer look at that chart. It lists seven

“hunter-gatherer” cultures as representative of prehistoric war-related male death. The seven cultures listed are the Jivaro, two branches of Yanomami, the Mae Enga, Dugum Dani, Murngin, Huli, and Gebusi. The Jivaro and both Yanomami groups are from the Amazon region, the Murngin are from northern coastal Australia, and the other four are all from the conflict-ridden, densely populated highlands of Papua New Guinea.

Are these groups representative of our hunter-gatherer ancestors?

Not even close.7

Only

one

of the seven societies cited by Pinker (the Murngin) even approaches being an immediate-return foraging society (the way Russia is

sort of

Asian, if you ignore most of its population and history). The Murngin had been living with missionaries, guns, and aluminum powerboats for decades by the time the data Pinker cites were collected in 1975—not exactly prehistoric conditions.

None

of the other societies cited by Pinker are immediate-return hunter-gatherers, like our ancestors were.

They cultivate yams, bananas, or sugarcane in village gardens, while raising domesticated pigs, llamas, or chickens.8 Even beyond the fact that these societies are not remotely representative of our nomadic, immediate-return hunter-gatherer ancestors, there are still further problems with the data Pinker cites. Among the Yanomami, true levels of warfare

are

subject

to

passionate

debate

among

anthropologists, as we’ll discuss shortly. The Murngin are not typical even of Australian native cultures, representing a bloody exception to the typical Australian Aborigine pattern of little to no intergroup conflict.9 Nor does Pinker get the Gebusi right. Bruce Knauft, the anthropologist whose research Pinker cites on his chart, says the Gebusi’s elevated death rates

had nothing to do with warfare.

In fact, Knauft reports that warfare is “rare” among the Gebusi, writing,

“Disputes over territory or resources are extremely infrequent and tend to be easily resolved.”10

Despite all this, Pinker stood before his audience and argued, with a straight face, that his chart depicted a fair estimate of typical hunter-gatherer mortality rates in prehistoric war. This is quite literally unbelievable.11

But Pinker is not alone in employing such sleight-of-hand to advance of Hobbes’s dark view of human prehistory. In fact, this selective presentation of dubious data is disturbingly common in the literature on human blood-lust.

In their book

Demonic Males,

Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson admit that war is unusual in nature, “a startling exception to the normal rule for animals.” But because intergroup violence has been documented in both humans and chimps, they argue, a propensity for war must be an ancient human quality, going back to our last common ancestor. We are, they warn, “the dazed survivors of a continuous, 5-million-year habit of lethal aggression.” Ouch.

But where are the bonobos? In a book of over 250 pages, the word

bonobo

appears on only eleven of them, and the species is dismissed as offering a less relevant sense of our last common

ancestor

than

the

common

chimpanzee

does—although many primatologists argue the opposite.12

But at least they

mentioned

the bonobo.

In 2007, David Livingstone Smith, author of

The Most

Dangerous Animal: Human Nature and the Origins of War,

published an essay exploring the evolutionary argument that war is rooted in our primate past. In his grisly accounts of chimps pummeling one another to a bloody pulp and eating each other alive, Smith repeatedly refers to them as “our closest non-human relative.” You’d never know from reading his essay that we have an equally close nonhuman relative.

The bonobo was left strangely—if typically—unmentioned.13

Amid the macho posturing about the brutal implications of chimpanzee

violence,

doesn’t

the

equally

relevant,

nonwarring bonobo rate a mention, at least? Why all the yelling about yang with nary a whisper of yin? All darkness and no light may get audiences excited, but it can’t illuminate them. This

oops-forgot-to-mention-the-bonobo

technique is distressingly common in the literature on the ancient origins of war.

But the bonobo’s conspicuous absence is notable not just in discussions of war. Look for the missing bonobo wherever someone claims an ancient pedigree for human male violence of any sort. See if you can find the bonobo in this account of the origins of rape, from

The DarkSide of Man:

“Men did not invent rape. Instead, they very likely inherited rape behavior from our ape ancestral lineage. Rape is a

standard

male reproductive strategy and likely has been one for millions of years. Male humans, chimpanzees, and orangutans

routinely

rape females. Wild gorillas violently abduct females to mate with them. Captive gorillas also rape females.”14 (Emphasis is in the original.)

Leaving aside the complications of defining

rape

in nonhuman species unable to communicate their experiences and motivations, rape—along with infanticide, war, and murder—has never been witnessed among bonobos in several decades of observation. Not in the wild. Not in the zoo.

Never.

Doesn’t that warrant a footnote, even?

The Mysterious Disappearance of

Margaret Power

Even apart from doubts raised by bonobos, there are serious questions worth asking about the nature of chimp “warfare.” In the 1970s, Richard Wrangham was a graduate student studying the relation between food supply and chimp behavior at Jane Goodall’s research center at Gombe, Tanzania. In 1991, five years before Wrangham and Peterson’s

Demonic Males

came out, Margaret Power published a carefully researched book,

The Egalitarians:

Human and Chimpanzee,

that asked important questions concerning some of Goodall’s research on chimpanzees (without, it must be said, ever expressing anything but admiration for Goodall’s scientific integrity and intentions).

But Power’s name and her doubts are nowhere to be found in

Demonic Males.

Power noticed that data Goodall collected in her first years at Gombe (from 1961 to 1965) painted a different picture of chimpanzee social interaction than the accounts of chimpanzee warfare she and her colleagues published to global acclaim a few years later. Observations from those first four years at Gombe had left Goodall with the impression that the chimps were “far more peaceable than humans.” She saw no evidence of “war” between groups and only sporadic outbreaks of violence between individuals.

These initial impressions of overall primate peace mesh with research published four decades later, in 2002, by primatologists Robert Sussman and Paul Garber, who conducted a comprehensive review of the scientific literature on social behavior in primates. After reviewing more than eighty studies of how various primates spend their waking hours, they found that “in almost all species across the board, from diurnal lemurs—the most primitive primates—to apes