Sex at Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality (34 page)

Read Sex at Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality Online

Authors: Christopher Ryan,Cacilda Jethá

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social Science; Science; Psychology & Psychiatry, #History

106 per mL pales in comparison to that of chimps, an impressive 548

×

106. But not all sperm competition is created equal.

For example, some species have seminal fluid that forms a

“copulatory plug,” serving to block the entrance of any subsequent sperm into the cervical canal. Species engaging in this type of sperm competition (snakes, rodents, some insects, kangaroos) typically wield penises with elaborate hooks or curlicues on the end that function to pull any previous male’s plug out of the cervical opening. Though at least one team of researchers reports data suggesting men who copulate frequently produce semen that coagulates for a longer time, copulatory plugs don’t appear to be in the human sexual arsenal.

Despite its lack of curlicues, the human penis is not without interesting design features. Primate sexuality expert Alan Dixson writes, “In primates which live in family groups consisting of an adult pair plus offspring [such as gibbons] the male usually has a small and relatively unspecialized penis.” Say what you will about the human penis, but it ain’t small or unspecialized. Reproductive biologist Roger Short (real name) writes, “The great size of the erect human penis, in marked contrast to that of the Great Apes, makes one wonder

what particular evolutionary forces have been at work.” Geoffrey Miller just comes out and says it: “Adult male humans have the longest, thickest, and most flexible penises of any living primate.”1 So there.

Homo sapiens:

the great ape with the great penis!

The unusual flared glans of the human penis forming the coronal ridge, combined with the repeated thrusting action characteristic of human intercourse—ranging anywhere from ten to five hundred thrusts per romantic interlude—creates a vacuum in the female’s reproductive tract. This vacuum pulls any previously deposited semen away from the ovum, thus aiding the sperm about to be sent into action. But wouldn’t this vacuum action also draw away a man’s own sperm? No, because upon ejaculation, the head of the penis shrinks in size before any loss of tumescence (stiffness) in the shaft, thus neutralizing the suction that might have pulled his own boys back.2 Very clever.

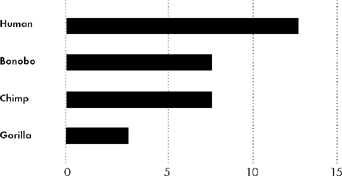

Penis Lengths of African Apes (cm)

Intrepid researchers have demonstrated this process, known as semen displacement, using artificial semen made of cornstarch (the same recipe used to simulate exaggerated ejaculates in many pornographic films), latex vaginas, and artificial penises in a proper university laboratory setting.

Professor Gordon G. Gallup and his team reported that more than 90 percent of the cornstarch mixture was displaced with just

a single thrust

of their lab penis. “We theorize that as a consequence of competition for paternity, human males evolved uniquely configured penises that function to displace semen from the vagina left by other males,” Gallup told

BBC

News Online.

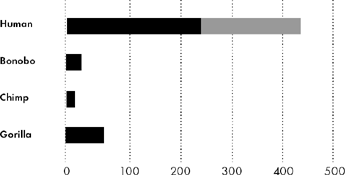

It bears repeating that the human penis is the longest and thickest of any primate’s—in both absolute and relative terms. And despite all the bad press they get, men last far longer in the saddle than bonobos (fifteen seconds), chimps (seven seconds), or gorillas (sixty seconds), clocking in between four and seven minutes, on average.

Average Copulation Duration (seconds)

The chimpanzee penis, meanwhile, is a thin, conical appendage without the flared glans of the human member.

Nor is sustained thrusting common to chimpanzee or bonobo copulation. (But really, how much sustained

anything

can you expect in seven seconds?) So while our closest ape cousins may have us beat in the testicles department, they lose to the human penis on size, duration, and cool design features.

Furthermore, the average seminal volume in a human ejaculate is about four times that of chimpanzees, bringing the total number of sperm cells per ejaculate within range of the chimp’s.

Returning to the question of whether the human scrotum is half-empty or half-full, the very existence of the external human scrotum suggests sperm competition in human evolution. Gorillas and gibbons, like most other mammals that don’t engage in sperm competition, generally aren’t equipped for it.3

A scrotum is like a spare refrigerator in the garage just for beer. If you’ve got a spare beer fridge, you’re probably the type who expects a party to break out at any moment. You want to be prepared. A scrotum fulfills the same function. By keeping the testicles a few degrees cooler than they would be inside the body, a scrotum allows chilled spermatozoa to accumulate and remain viable longer, available if needed.

Anyone who’s been kicked in the beer fridge can tell you this is a potentially

costly arrangement. The increased

vulnerability of having testes out there in the wind inviting attack or accident rather than tucked away safely inside the body is hard to overstate—especially if you’re crumpled in the fetal position, unable to breathe. Given the unrelenting logic of evolutionary cost/benefit analyses, we can be quite certain this is not an adaptation without good reason.4 Why carry the tools if you don’t have the job?

There is compelling evidence pointing to a dramatic reduction in human sperm production and testicular volume in recent times. Researchers have documented worrisome decreases in average sperm count as well as reduced vitality of the sperm that do survive. One researcher suggests that average sperm counts in Danish men have plummeted from 113 × 106 in 1940 to about half that in 1990 (66 × 106).5 The list of potential causes for the collapse is long, ranging from estrogen-like compounds in soybeans and the milk of pregnant cows to pesticides, fertilizers, growth hormones in cattle, and chemicals used in plastics. Recent research suggests the widely prescribed antidepressant paroxetine (sold as Seroxat or Paxil) may damage DNA in sperm cells.6 The Human Reproduction study at the University of Rochester found that men whose mothers had eaten beef more than seven times per week while pregnant were three times more likely to be classified as subfertile (fewer than twenty million sperm per milliliter of seminal fluid). Among these sons of beef eaters, the rate of subfertility was 17.7 percent, as opposed to 5.7 percent among men whose mothers ate beef less often.

Humans seem to have much more sperm-producing tissue than any monogamous or polygynous primate would need.

Men produce only about one-third to one-eighth as much sperm per gram of spermato-genic tissue as eight other mammals tested.7 Researchers have noted similar surplus capacities

in

other

aspects

of

human

sperm

and

semen-production physiology.8

The correlation between infrequent ejaculation and various health problems offers further evidence that present-day men are not using their reproductive equipment to its fullest potential. A team of Australian researchers, for example, found that men who had ejaculated more than five times per week between the ages of twenty and fifty were one-third less likely to develop prostate cancer later in life.9 Along with the fructose, potassium, zinc, and other benign components of semen, trace amounts of carcinogens are often present, so researchers hypothesize that the reduction in cancer rates may be due to the frequent flushing of the ducts.

A different team from Sydney University reported in late 2007 that daily ejaculation dramatically reduced DNA damage to men’s sperm cells, thereby

increasing

male fertility—quite the opposite of the conventional wisdom.

After forty-two men with damaged sperm were instructed to ejaculate daily for a week, almost all showed less chromosomal damage than a control group who had abstained for three days.10

Frequent orgasm is associated with better cardiac health as well. A study conducted at the University of Bristol and Queen’s University of Belfast found that men who have three or more orgasms per week are 50 percent less likely to die from coronary heart disease.11

Use it or lose it

is one of the basic tenets of natural selection.

With its relentless economizing, evolution rarely equips an organism for a task not performed. If contemporary levels of sperm and semen production were typical of our ancestors, it is unlikely our species would have evolved so much surplus capacity. Contemporary men have far more potential than they use. But if it’s true that modern human testicles are mere shadows of their former selves, what happened?

Since the infertile leave no descendants, it’s a truism in evolutionary theory that infertility can’t be inherited. But

low

fertility

can be passed along under certain conditions. As discussed above, chromosomes in humans, chimps, and bonobos associated with sperm-producing tissue respond very rapidly to adaptive pressures—far more rapidly than other parts of the genome or the corresponding chromosomes in gorillas, for example.

In the reproductive environment we envision, characterized by frequent sexual interaction, females would typically have mated with multiple males during each ovulatory period, as do female chimps and bonobos. Thus, men with impaired fertility would have been unlikely to father children, as their sperm cells would have been overwhelmed by those of other sexual partners. The genes for robust sperm production are strongly favored in such an environment, while mutations resulting in decreased male fertility would have been filtered out of the gene pool, as they still are in chimps and bonobos.

But now consider the repercussions of culturally imposed sexual monogamy—even if enforced only for women, as was often the case until recently. In a monogamous mating system where a woman has sex with only one man, there is no sperm competition with other males. Sex becomes like an election in a dictatorship: just one candidate can win, no matter how few votes are cast. So, even a man with impaired sperm production is likely to ring the bell

eventually,

thus conceiving sons (and perhaps daughters) with increased potential for weakened fertility. In this scenario, genes

associated with reduced fertility would no longer be removed from the gene pool. They’d spread, resulting in a steady reduction in overall male fertility and generalized atrophy of human sperm-production tissue.