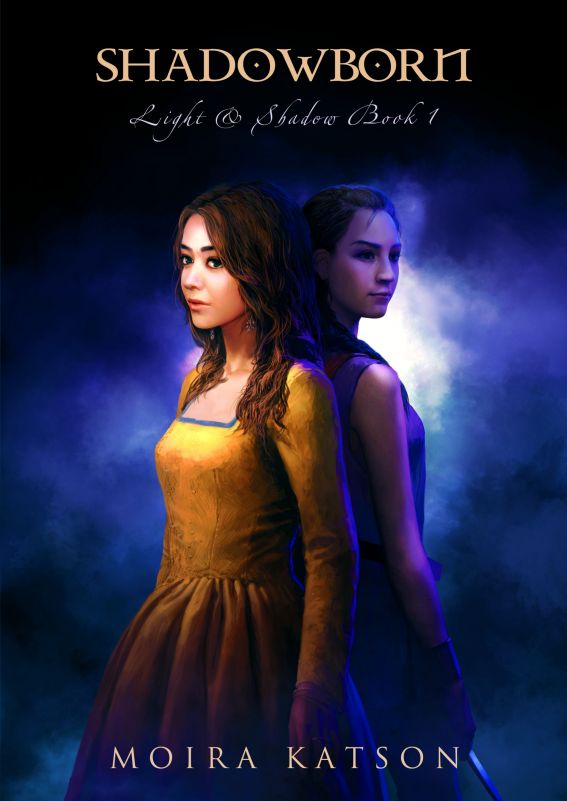

Shadowborn (Light & Shadow, Book 1)

Light and Shadow, Book 1

By Moira Katson

All rights reserved, including the right of

reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

Cover art by Zezhou Chen.

Book II: Shadowforged

Book III: Shadow’s End

Mahalia

Inheritance

Origins

whose support, encouragement, and

feedback

have helped me to take this leap!

Excerpt of Shadowforged (Book

II)

Cast of

Characters

The Duke’s Household

Catwin – servant to the Duke, Miriel’s

Shadow

Donnett – a member Palace Guard, who fought

with the Duke at the Battle of Voltur

Eral Celys – Duke of Voltur

Emmeline DeVere – younger sister of the

Duke, Miriel’s mother

Miriel DeVere – niece of the Duke, daughter

of Emmeline and Roger DeVere

Temar – servant to the Duke, the Duke’s

Shadow

Roine – a healing woman, foster mother to

Catwin

Members of the Royal Family: Heddred

Anne Warden Conradine – sister of Henry,

aunt of Garad; Duchess of Everry

Arman Dulgurokov – brother of Isra

Cintia Conradine – daughter of Anne and

Gerald Conradine

Elizabeth Warden de la Marque – cousin of

Henry, mother of Marie

Henry Warden– father of Garad

(

deceased

)

Garad Warden – King of Heddred

Gerald Conradine – husband of Anne; Duke of

Everry

Guy de la Marque – husband of Elizabeth

Warden, father of Marie; Royal Guardian to Garad

Isra Dulgurokov Warden – mother to Garad,

widow of Henry; the Dowager Queen

Marie de la Marque – daughter of Elizabeth

and Guy

Wilhelm Conradine – son of Anne and Gerald;

heir to the throne

William Warden – Garad’s uncle, Henry’s

older brother (

deceased

)

Members of the Royal Family: Ismir

Dragan Kraal – brother of Dusan, father of

Kasimir (

deceased

)

Dusan Kraal – King of Ismir

Jovana Vesely Kraal - Queen of Ismir

Kasimir Kraal – nephew to Dusan

Marjeta Kraal Jelinek – daughter of Dusan

and Jovana

Vaclav Kraal – son of Dusan and Jovana, heir

to the Ismiri throne

Heddrian Peerage

Edward DeVere – courtier; Duke of

Derrion

Efan of Lapland - courtier

Elias Nilson – son to Piter; betrothed to

Evelyn DeVere

Elizabeth Cessor – daughter of Henry and

Mary Cessor

Evelyn DeVere – daughter of Edward,

betrothed to Elias Nilson

Henri Nilson – brother of Piter

Henry Cessor – courtier, father of

Elizabeth

Henry DeVere – courtier, younger brother to

Edward

Linnea Torstensson – a young maiden at

Court; daughter of Nils

Maeve d’Orleans – a young maiden at

Court

Piter Nilson – Earl of Mavol

Roger DeVere – father of Miriel DeVere

(

deceased

)

Other

Anna – a maidservant in service to the

Duke

The High Priest – head of the Church in

Heddred; advisor to the Dowager Queen

Jacces – leader of a populist rebellion in

the Norstrung Provinces

Chapter 1

I was an ice child, having the ill luck to

be born early, in the deepest storms of the winter, when the drifts

of snow can bury whole caravans without a trace, and the winds will

cut a man open with slivers of ice. So they say, in any case, in

the village in which I was born, the village huddled at the base of

the mountain that houses the Winter Castle, the last outpost before

the road winds west into Ismir.

And so, ill luck to me, and ill luck to my

mother, for I came months early. The peasants who make their living

in the unforgiving world of the mountains are notoriously

superstitious, but it does not take superstition to make ill luck

of a birth in a blizzard. With no way to call for a midwife, the

birth nearly killed her, small as I was, and when it was over, she

and I huddled together in the drafty little hovel, wrapped in the

only blankets the family could afford. I, despite being undersized

and weak, screamed to high heaven, and my mother, being half-dead

of blood loss, slipped into a fever and spoke like a madwoman.

So it was that the sorceress Roine was

called from the great castle itself, and she made her way down the

steep steps, in the biting cold, to see me and cure my mother. Her

poultices and teas—“Aye, and spells,” the maids whispered

knowingly—brought down the fever, and at last my mother’s soul

returned from its wandering in the lands of the dead, and came back

to her body.

Roine begged my mother’s leave to take me to

the castle itself until I was stronger. The Lady had given birth

not a month past, Roine told my mother. The wet nurse could take

another child, and there was goat’s milk as well, and Roine had all

of her herbs. It would spell my mother, so she could recover as

well. When I was healthy and strong, Roine would bring me back.

“

And then what?” I begged

to know when I first heard the story. I was six years old, and in

the way of children, I had taken a liking to one of the maids,

Anna, and had followed her on all of her chores, dogging her heels

and clinging to her dress despite her sharp words to go sit by the

fire. Finally, when she had told me that she had no time for a

cuckoo’s child, I had demanded to know what that meant. Anna, tired

of my questions and eager to teach me a lesson, had been only too

happy to tell me the story.

“

And then,” she said,

leaning towards me, and smiling, eyes bright with malice, “your

mother said not to bring you back. She didn’t want you back at all,

for she said you were a cursed child.” I stared at her.

“

So?” I asked. I had been

raised by Roine, a woman I knew was not my mother. I knew that

other people had mothers, but I had only the dimmest concept of

what mothers actually were. In the self-centered way of children, I

had never wondered much about them, and so I could not be entirely

sure what to think about this new development—although I was

somewhat offended, even at that young age, that someone had not

wanted me around.

“

Cursed,” Anna

repeated.

“

Well, what does

that

mean?” It was my

favorite question at the time. Anna did not think much of it,

having been subjected to an entire morning of the query.

“

Go ask Father Whitmere if

you don’t know,” she said rudely, and I—not thinking highly of

Father Whitmere—heaved a great sigh and went to go find Roine

instead.

Roine sighed as well when she heard my

question, and she set aside her spindle and lifted me onto her lap,

where she ran her fingers through my fair hair as she talked. I

leaned back and looked up into her beloved face, and I wondered, as

I often did, why it was that Roine always looked sorrowful.

“

Your mother did not say

you were cursed,” she said. “She told me that you were born to be

betrayed.”

“

Well, what does

that

mean?” I demanded

at once, and Roine considered.

“

What do you think it

means?” she asked, finally, and I shook my head so that my braid

flopped about.

“

I don’t know.”

“

Neither do I.” Roine

kissed my forehead and set me down on the floor again. “Maybe it

means nothing.”

“

I don’t think so,” I said

stoutly. “How could it mean nothing?”

Roine had a peculiar look on her face. “One

can always hope,” she said.

“

Did anyone ever say

something like that about you?” I asked, for a moment she went

quite pale.

“

Not quite like that,” she

said. “Now run along, and keep out of the way. The Duke is coming,

and there is much to prepare.”

The Duke. The one terror of my childhood was

the Duke, the Lady’s brother. Her husband had died in the war, and

the Lady had never remarried; she lived in this castle on the

charity of the Duke, some said as a half-prisoner. I heard servants

whisper that she wished to go back to the court, but he would not

allow her—not after what had happened the last time. When they

spoke of it, the servants would laugh in a way that I, as a child,

could not quite understand, and once or twice it was murmured that

Miriel was lucky she had her father’s hair, her father’s eyes.

The Lady might plead with the Duke—and, to

be sure, there were always eavesdroppers to those conversations,

and whispered accounts of her begging, and his cold refusals—but

she would never defy him. No one defied the Duke. When he rode into

the Winter Castle, it was with a great train of retainers and

soldiers and priests, all wearing black and looking as grim as

their lord. As if the soldiers were not terrifying enough, and the

priests in their robes, like a flock of ravens, the Duke went

nowhere but that he was accompanied by Temar, the man they called

his shadow—and, some whispered, his assassin.

Worse, this grim man was the sole authority

in my world. If the Lady could not make a decision, she would say,

“I will write to the Duke.” If someone would not obey, she said,

“it is the Duke’s order.” If I misbehaved, from stealing a pastry

to breaking a statue, the maids told me, “I’ll tell the Duke on

you,” and I was told, in excruciating detail, just how the Duke had

tortured a man to death once, or how he had put down a rebellion in

the south, or just how he had won the Battle of Voltur, or how…

until I ran away in tears.

Having a mortal terror of the Duke, who had

most likely never noticed me at all, I had decided that the best

way to avoid his wrath was to avoid being seen, and so I had become

very good at that. I practiced by sneaking around after the maids

on their chores, or the soldiers on their rounds. I knew where to

stand so that the candlelight would not glint off of my hair as

much, and I knew how shadows fell in doorways, and I knew how to

move very quietly, and very quickly.

On his visit that day, the Duke took not the

slightest notice of me. Nor did he see me the next time he came, or

the next, or the time after that. For each visit, there were feasts

in his honor, and Miriel, the Lady’s daughter, was paraded out and

shown off. Each time, he was said to test her, to make sure that

she was perfect. Never mind that the little girl was as isolated

from the world as a girl could be—she must still be able to dance,

and sing, and dress as finely as any lady of the Court. The Duke

expected perfection from her, it was said.