Shame of Man (40 page)

Authors: Piers Anthony

“But what of the time I played?” Hyu asked.

“The envoys set it up,” Itti said. “You played well. I have never heard such music! The emperor listened without apparent emotion. But then he indicated that he wanted to see the author of the music, and they could not refuse him. The emperor knew your situation. The envoy would have prepared you for the encounter, acquainting you with the proper forms, but no one knew this would happen.”

“I think he liked the melody,” Hyu said.

“The whole city was agog as we departed. The emperor did you great honor. He acknowledges no one without excellent reason. And yet all those who heard you play there understood. The spirits were surely with you.”

“They surely were,” Hyu agreed, gratified.

Later the clouds piled up to the south-southwest, directly in their path. “You didn't—?” Itti asked Hyu, his face lining with worry.

“I did not violate any part of my role,” Hyu said. “Much thanks to you.”

The captain ignored the irony. “Then that storm will slide past us harmlessly.” He was not being humorous or casual; he really believed it, and thus his underlying faith was revealed. He might deny the influence of the spirits when there was no threat, but he was quick to accept it when there was a threat.

The storm loomed darkly, and its inflowing winds carried the ship swiftly toward it. But the storm was moving north, and by the time the ship drew close, the peripheral winds remaining in the route were manageable. In fact they made better time than they might have, because of the storm's boost. The spirits were teasing them, but helping rather than hurting. Soon enough they made it to land, and all was well.

The captain's judgment proved to be valid. The emperor had not only accepted the gifts, he had sent gifts of his own: blue silk, white silk, gold silk, dragon-embossed silk, pearls, valuable red pigment, and a sword

almost as long as a man. He had also conferred high titles upon the envoys, and given them special awards. The scroll expressed his extreme pleasure, and Queen Himiko's own pleasure was not long in being felt.

Hyu knew what this meant to him and his family. Yet what remained foremost in his mind was the way the palace ceiling had enhanced his melody, and the emperor's slow nod. Surely Hyu's children's children would someday learn of that.

Himiko ruled securely until

A.D.

244 before she had a problem with a neighboring king. She sent to the emperor for support, and he provided it. But Himiko died before the envoy returned. She was buried beneath a mound more than a hundred paces in diameter, and a hundred men and maidservants were buried with her. The Yoshinogari site is the oldest known large mound burial in Japan, making it seem likely to be Himiko's.A king succeeded her, but civil unrest followed, with assassinations becoming commonplace

—

exactly as had been the case before Himiko's ascension. Finally a thirteen-year-old girl named Iyo, a relative of Himiko, was made queen, and she restored order. The Chinese emperor supported her, and an exchange of gifts occurred. It seems that peace and prosperity remained until the time when men achieved power again, and the Yayoi culture disappeared. If there is a lesson here, it seems to have been lost on men.

CHAPTER 14

MOSLEM

In the Year of the Elephant, according to tradition, or about

A.D.

570, a boy was born in Mecca, Arabia. Orphaned by age five, Muhammad was raised by an uncle. At age twenty-five he married a rich forty-year-old widow, and it was a happy union. But he was disturbed by the corruption that flourished in the name of religion; there were 360 idols in Mecca. In 610 he heard bells and a voice enjoining him to recite the nature of Allah, a single god. Thus, in time, came to be the Moslem religion. The Prophet died in

A.D.

632, having unified a number of Arab tribes by preaching and force of arms. His successors continued similarly,

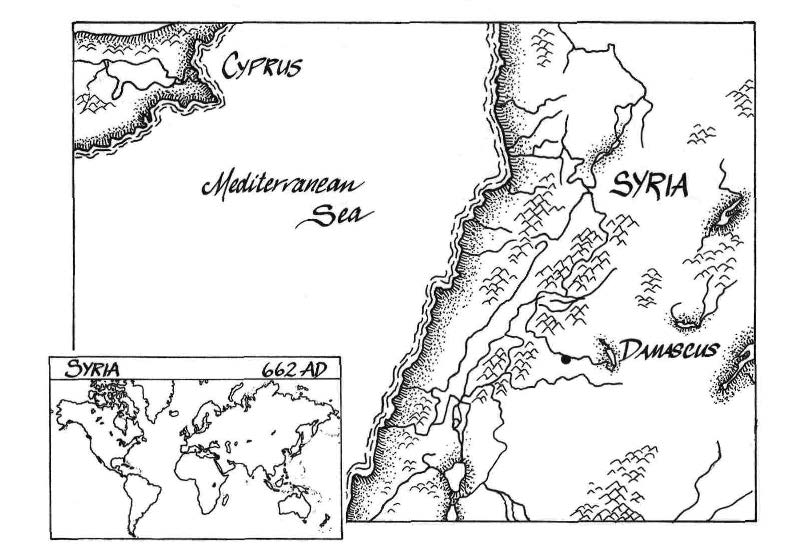

securing all Arabia, then expanding operations to neighboring Palestine, Syria, and Mesopotamia. In these regions there had been constant strife, weakening their governments, and the local populace welcomed the forces of Islam as liberators. Cities that surrendered without fighting were treated leniently. Thus Islam spread rapidly, soon amassing globally significant territory. But by

A.D.

655 the unity of the new empire was crumbling; factions were quarreling. Muhammad's cousin Ali, who had married the Prophet's daughter Fatima, became the dominant figure, but strife was constant. In 661 Ali was assassinated

—

and became revered in death as he had not been in life. His supporters are known today as the Shiites. Power then shifted to Muawiya, the governor of Syria, a skilled statesman, who moved the capital from Mecca to Damascus and established the century-long rule of the Umayyad caliphs.

O

NCE the joy of Huo's return, and the family's restoration of status, had been celebrated, they held a family council. The Bedouin Huo had been implicated in the Caliph Ali's assassination by a poisoned blade, but his pilgrimage to Mecca had established his piety, and new evidence had absolved him. But Arabia was the region of his degradation, and he wasn't sure he wanted to remain here.

First they went out as a family for the dawn devotion, prostrating themselves in the direction of Mecca, the Holy City. Then they discussed their prospects.

“But where else could we go?” An'a asked for the benefit of the children. They had already discussed it privately, but preferred family unity.

“The Caliph Muawiya has invited me to play for him in Damascus,” Huo said. “He will even provide my family with good lodging.”

“But you supported Caliph Ali!” Chi'ip exclaimed. He was eleven, and knew what was what.

“But Caliph Muawiya fought Caliph Ali,” Miina reminded him. She was nine, and a midnight-haired beauty despite her youth. Huo knew that when she had a body to go with her face, she would be a dancer like no other.

“So the fact that I may have had a problem relating to Ali's death does not bother Muawiya,” Huo said. “He suspects that though I supported him, my position among his other supporters has been weakened because of their attempt to implicate me unfairly. And he is right. I am no longer eager to associate with them.”

“The man is clever about such things,” An'a remarked.

“He sure is,” Chi'ip said enthusiastically. “When he fought Ali at Siffen, Ali had 50,000 troops and was winning, until Muawiya's men tied pages of the Koran to their lances, saying, ‘Let Allah decide.’ So they had to go to arbitration, and Muawiya didn't get beaten.”

“And when they wanted to call Ali's son Hasan the new caliph,” Miina said, eager to show that she knew about politics too, “Muawiya sent him a

note that said: ‘Ask what thou wilt,’ and enclosed a blank sheet of paper with Muawiya's signature on it. And Hasan took the money of the town treasury and went with his wives and harem to Medina, and renounced his claim to power.”

Huo nodded. “Muawiya never uses the sword where the lash suffices, and spares the lash where his tongue is enough. He makes lavish gifts to his enemies, because a war costs infinitely more. He has an administrative staff made up largely of Christians, because they are competent and have no ambitions to weaken his power, on which theirs depends. Christians and Jews aren't truly unbelievers, because the Prophet named them ‘People of the Book.’ He is clever and devious throughout. So now should I join him on a similar basis—as a nonsupporter to whom he is being generous?”

“Yes, because our own kind did us dirt,” Chi'ip said righteously.

But Miina wasn't so certain. “It's a long journey. What is Damascus like?”

“It was perhaps the wealthiest city of the Byzantine Empire,” Huo said. “It surrendered to the faithful after a six month siege, so wasn't ravaged, and remains prominent. The Christians and Jews are allowed not only to remain, they can continue their idolatrous worship and run their businesses, as long as they pay their taxes. Any citizen can ask for and receive an audience with the caliph, and many do. So it is an interesting, cosmopolitan place.”

“Even I could meet the caliph?” Miina asked, awed.

“Even you, I think,” Huo agreed.

She nodded. “Then we can go.”

Damascus was indeed impressive. Mecca might be the Holy City, but Damascus was huge and beautiful. It had been left as it was, expect for one thing: the caliph was constructing a palace of green marble and painted ceilings. Here he would be able to hold court in style, sitting cross-legged on golden cushions, with his paternal relatives to his right and his maternal relatives to his left, all dressed in their silks and brocades. There would be plenty of room for the lawyers and secretaries and poets and guild masters, too, along with a plethora of minor officials. But at the moment the most splendid building was the enormous Christian church, where there were human figures painted on the walls. No Moslem Mosque would tolerate such forbidden art, of course, as it constituted the worship of idols, but allowance had to be made for those who didn't know better.

The apparel of the city folk was surprising too. Huo was of course garbed in loose trousers, loose shirt, loose jacket overall, and a turban on his head and scarf wrapped around his lower face, so as to keep the sun and sand out, and An'a was covered just as thoroughly. But the people of Damascus ranged from Bedouin style to garish Christian style, with many of them

completely and shamelessly barefaced. Their clothing was of every color, and some young women exposed so much of their wrists and ankles that it was hard not to stare.

But all were unified at the five times for universal prayers. At dawn, noon, afternoon, sunset, and darkness all Moslems faced Mecca, went to their knees, and down on their faces, all together. It was a phenomenal synchronized display of the worship of Allah, the one God, and devotion to his prophet Muhammad. However else the city might be strange, this proved it to be familiar in the faith.

It was familiar, in a less comfortable way, to Huo. The left hand was considered to be a thing of impiety. The left was used in the performance of the cruder bodily functions, and the right for all elevated tasks. The difference between superficially similar hands was like that between the manners in which the body expelled air: a belch after a good meal was excellent form, while an inadvertent breaking of wind was a social horror of the grossest magnitude. Thus Huo had to eat and write with his right hand, though it was clumsy for him. Only when alone with An'a, who understood, and when playing music, where both hands were equal, could he relax. Often he wished he could be in some other culture, where he could be himself. But that was a pointless dream; everything that he valued was here in the land of the faithful.

But they could not spend too much time gawking at the wonders of the city. They had to locate the promised lodgings before nightfall.

A man approached Huo. “Are you the musician from Arabia?” he asked.

“I do answer to that description,” Huo agreed cautiously.

“Here is a letter from the caliph.” The man handed him a scroll, saluted smartly and departed.

An'a and the children stared after him. “A what?” she asked.

“I seem to remember that the caliph has established a postal service,” Huo said, bemused. “And a system for archiving and protecting official documents. I had not expected to encounter it so quickly.”

“What does it say?” Chi'ip asked.

Huo broke the seal and read the ornate text. “It says that we have been assigned a residence in the elite section, with a servant who knows the city to take care of routine matters. It gives the address, and requests an audience tomorrow.”

“Who requests an audience?” An'a asked.

“It is signed ‘The Barking Bitch.’ “

Both children burst out laughing. But An'a was thoughtful. “Doesn't Muawiya's name mean that?”

“Yes,” Huo said. “But I never thought he would use it himself. I fear that this may be a false message.”

“Unless the caliph has a considerable sense of humor.”

“I think we shall just have to check the address, and see what we can discover,” Huo said.

They made their way to the lodging, and it was a nice section of the city, clean and without dangerous-looking people. Huo approached the door, and was met there by a young woman. “Are you the musician?” she asked.

“I am. I received a letter—”

“Yes. Come in with your family. I am your servant Mou'se. I will do your shopping, take care of your children, and guide you wherever you need to go. Tomorrow you must see the caliph.”

“The letter was signed ‘The Barking Bitch.’ That couldn't be the caliph!”

Mou'se smiled. “It is the humor of the scribe. Caliph Muawiya is tolerant of such jests, so long as they are not uttered by powerful enemies. He is also called the brother of a bastard, and accused of having enormous buttocks. All true, of course, but—”

“But we shall not call him anything but Caliph,” Huo said firmly, looking at his children, who were starting to giggle. They sobered immediately.

“What is your family, and how did you come to be assigned to this chore?” An'a asked Mou'se.

“Oh, I like helping folk,” Mou'se said. “My family lived in the country, but the drought made us move to the city. So my father and mother, and my two older sisters, and my brother and his lovely wife Se'ed all came here, and we remember how hard it is to get used to at first. Even twenty years later. And I love music.”

That seemed to cover it. They entered the house and Mou'se made them feel right at home. She had food ready, and quickly acquainted them with all the necessary things to know about the city. This was their first experience with a servant, but in just a few hours it seemed as if she had always been with them.

“Do the Bedouin still value eloquence, archery, and horsemanship above all else?” Mou'se inquired shyly. “I was only five when—but that is of no interest.

“The old values still hold,” Huo agreed. “Our proverb states that the three great boons to a clan are the birth of a son, the foaling of a mare, and the discovery of a poet.”

“I remember!” Mou'se exclaimed. “And music is like poetry. I hope I hear you play one day.”

“Perhaps,” Huo agreed, flattered but wary. It was true that his ability with the double clarinet had lifted him from the commonplace to the rare, and given him access to prominent families and courts. Until his implication in the death of a caliph, and banishment from recognition. Now his reputation had been restored, but he retained a certain nervousness about what could happen in a royal court.

In the evening they found themselves too tired to go back out into the

city, but still too tense from travel and new experience to relax. The children were showing signs of becoming cranky, and An'a feared they were about to make a scene that would embarrass them in front of an outsider.

But Mou'se, alert to exactly that, stepped in. “Let me tell you a tale of Persia,” she said. “It is a wondrous story that always enthralled my sisters and me.”

Chi'ip looked doubtful, afraid that Huo and An'a might be planning to go out and leave him and Miina with the servant.

A tale of Persia. Huo found himself intrigued. “We'll all listen,” he said, taking a comfortable seat. That reassured the children, and they relaxed.

Mou'se began the tale of “The Enchanted Horse.”

There was once, in times of yore and the passage of ages, a great and wise king of the Persians named Sabur. He had a son who was handsome and bold, and three daughters who were like three moons or three wonderful flowers in their beauty and delicacy. He had a great love of science, geometry, and astronomy, and encouraged these disciplines in his kingdom.

One day during a spring festival three sages presented themselves before King Sabur. They had come from several far countries, and each spoke a different language. The first was a Hindu from India, and the second was a Christian from Constantinople, and the third was a Persian from a distant province of the king's own realm.

The Hindu sage brought a truly royal present: a man formed from gold encrusted with diamonds, with a golden trumpet in his hand. “If you set him up at the gate of your city, he will be a sleepless guardian. If an enemy approaches, the golden man will blow a blast which will paralyze your foe with fear and alert your entire city to the danger.”