Shame of Man (43 page)

Authors: Piers Anthony

“Yes. It had no fault in itself, only serving its masters. But folk do not always distinguish between things and the uses to which they are put.”

How true that was, Huo thought, thinking of the problem of his hands.

“We thank you for the marvelous tale,” An'a said. “Now it grows late, and we must retire.” Indeed, both children were obviously sleepy.

Mou'se helped in that too, seeing to the children's evening rituals while Huo and An'a saw to their own. “I could get used to having a servant,” Huo murmured as they lay for sleep.

“Maybe you could take her for a second wife,” An'a suggested. “She is unmarried, and a year younger than I am.”

“She is twenty-five?” he asked, surprised. “She seemed younger.”

“Perhaps because of her animation as she spoke of the youngest princess. She is overdue for marriage, perhaps not yet having found a good man.”

He considered it. A man was entitled to four wives, if he could maintain them, as well as servants and slaves. The later wives were in effect the servants of the first wife, so often this strengthened a marriage. Mou'se did seem to be a fine woman, of pleasing physical aspect and personality. But it did not seem right for him. “One wife fills all my aspirations.”

“So I am to have no relief in bed?” she inquired mischievously.

“None at all,” he agreed, kissing her.

The kiss proceeded to more, to his surprise; he had intended to let her rest. Then he realized that she was the animating force in this encounter, and by this token knew that she was pleased with his decision. So they made love despite being tired, and it was as if they remained young and passionate, despite being in their mid-twenties.

Next morning the family went for their audience with the caliph, who had insisted on meeting all of them, rather than just Huo. Muawiya turned out to be a potbellied old man of benign disposition, whose turban was slightly askew. When she saw him, Miina tittered. An'a hastily silenced her, but the caliph had noticed.

“Come here, child,” he said.

Miina, suddenly mortified, come forward, looking woeful. But the caliph smiled. “Tell me the truth, child,” he said. “Was it my appearance that made you laugh?”

She prostrated herself before him. “O great Caliph, I meant nothing by it!” she cried. “Please don't slay my family!”

“Oh, get up, child. No one will be slain. I know I am a funny-looking man, and anyone who says otherwise is trying to deceive me. You would not try to deceive me, would you?”

Wordlessly, she shook her head.

“In fact, my appearance is laughable. Is that not so?”

She started to deny it, but caught his look and nodded.

“So we have no quarrel, do we?” She nodded. “But you, in contrast, are beautiful. I think you must be a dancer.” She nodded. “So I have made you laugh. Now you must make me smile. Dance for me.” He looked around. “Have we a musician near?” Huo lifted his double clarinet. “Yes, so we do. I love the arts. Play for my dancer.”

So Huo played, and Miina danced, at first cautiously, and then with abandon as she saw that the caliph was enjoying it. Indeed, she was good at it, and soon all the palace attendants were watching. After a while, the caliph signaled to An'a, whose lithe lines he evidently recognized, and she came out to join her daughter in the dance. They made a beautiful couple, the full-bodied woman and the almost-bodied girl.

“So there we are,” the caliph said as they finished. “Now I think we are introduced.” He snapped his fingers. “Bring pastries and milk for my guests and me.”

Thus readily did they find themselves in audience with the caliph, who was exactly as reputed to be. Still, the informality surprised them. “We have never met before,” Huo said. “You know we supported the Caliph Ali. How can you trust us so close, so soon?”

“I never met an assassin yet who brought his children along,” Muawiya said. “And Ali was a good man. Just not skilled in negotiations. While he lived, your loyalty was to him; will it be to me, now, while I live?”

“Yes.”

“I trust you because of your demonstrated loyalty. If you would not play him false, you will not play me false. That is more than can be said for those who put you under an unnecessary cloud.”

“Yes!” Chi'ip exclaimed. Then he was abashed, realizing that he shouldn't have spoken.

But the caliph merely nodded. “The young express themselves more freely, therefore can be trusted. Tell me, young man: do you know the origin of the Arabs and the Israelites?”

“Yes, Caliph,” Chi'ip said, surprised.

“Then advise me of it, for I seem to have forgotten.”

“Two thousand years ago the patriarch Abraham left his home in Ur of the Chaldees and went to dwell in Palestine,” Chi'ip said promptly. “His wife Sarah seemed barren, so she had him wed a slave girl named Hagar. Hagar bore him a son, Ishmael. Then Sarah had a son, Isaac. This caused trouble between the two women, for each wanted her son to inherit Abraham's wealth. So Abraham had to separate them. He took Hagar and Ishmael to the Valley of Mecca, which was then a lonely rest stop for caravans, and left them there with provisions, while he returned to Sarah.”

“He left them alone in a far place?” the caliph asked, affecting surprise. “Was that right?”

“No,” Chi'ip said. “Hagar had done him no evil, and had borne him his first son. But Sarah was his first wife, so he had to support her. It was very

dry in Arabia, and Hagar was frantic; they were running out of water. But Ishmael dragged his heel through the sand, and there was water. It was a good spring, which became the well of Zamzam, which we revere today. Now it was possible to settle there, and so there came to be the great city of Mecca. Abraham visited Hagar, and helped Ishmael build the Kaaba, the shrine that is the holiest place in Islam, with a sacred black stone from the sky in its wall. Ishmael married a woman of the new settlers, and their children became the Arabs, while the children of Isaac became the Israelites.”

“Ah, yes, I remember now,” the caliph said. “And so we are of a single ancestry, and we Arabs recognize the prophets of the Israelites, and we recognize the Prophet Jesus of the Christians too. So there is no actual need for us to quarrel over the name of God, is there?”

Both children stared at him, uncertain whether he was testing or teasing. But he just laughed. “After all, do we not face toward the Holy City of Jerusalem five times a day in worship?”

“No!” the children said together.

“No? Where do we face, then?” He looked at Miina.

“Toward Mecca,” she said promptly.

“But why?”

“Because it's the Holy City.”

“And Jerusalem is not?”

That stumped them.

“I will tell you,” the caliph said. “At first we did pray toward Jerusalem. But then the Israelites in Mecca supported a faction that opposed the Prophet Muhammad, and that annoyed him, so he turned the face of our faith away from their holy city of Jerusalem and toward Mecca, and so it has been thereafter.”

They were amazed.

Muawiya looked at Huo. “So you see, I know you, through your children. They are loyal and well instructed. Now I have two situations available, and I do not know which is better for you. I need good musicians and dancers here in Damascus, for as you know the arts are dear to me, but I also need them in the far reaches of our expanding empire. There is an island called Bahrain that is to be settled by a contingent of the followers of Ali, and their need for cultural reinforcement is great. It is so far distant that contacts will be few, and those musicians and dancers that go there will be prominent. But because it is distant, and because of the uncertain alliance of the force going there, I prefer to have among them those I can trust.”

Huo was chagrined. “You are sending us away?”

“By no means! I am offering you a choice. You may remain here in good favor, and perform among those who match you in skills, or you may go to some other settled region of the empire and be leading musicians and dancers, or go to the island and be the master performers of the region. I

leave the choice to you. I will welcome what you choose, for I want you to be satisfied.” And he sat back, awaiting their decision.

Huo looked at An'a. This sudden decision would affect the rest of their lives, and they had to make it immediately, lest they try the caliph's patience. They could be two among many in a rich city, or well favored in a lesser city, or leaders at the fringe of the empire. What should they say?

The power of Islam continued to expand, and today it remains one of the great religious and cultural centers of the world. At one time Islam controlled Spain and southern France, and at another time a significant portion of eastern Europe. Much of Africa, India, and Indonesia is Moslem, and there is a significant contingent in central Asia. The discovery of oil in the Moslem heartland brought riches to a number of nations. The Dark Ages of Europe were not dark for the sons of the Prophet, where a high level of culture was maintained throughout.

One of the monuments of literature is the framework of the Arabian Nights, by tradition a series of tales Scheherazade told to a king over a thousand nights to distract him from killing the women of his kingdom. They reflect the culture, with the added elements of fantasy and human frailties. “The Enchanted Horse” is typical of these entertainments.

CHAPTER 15

MYSTERY

When the Spanish Conquistadors came to America they found several prominent cultures: the Aztec in the north, the Maya in the central, and the Inca in the south. They destroyed them all, though it would have been a different story had the native Americans understood the nature of the threat at the outset, instead of welcoming the strangers and their devastating diseases and greed. What is not as widely known is that American culture had been evolving for five thousand years, and in certain respects matched or exceeded that of the invaders. The Maya calendar was the most accurate known, and some of their pyramids

are more massive and elegant than those of Egypt. The Inca network of highways and aqueducts was reminiscent of those of the Romans, and their artistic metalwork was phenomenal. These achievements were built on those of prior peoples, which were less impressive but nonetheless solid. In South America things were in transition; the Moche state gave way to the Huari Empire circa

A.D.

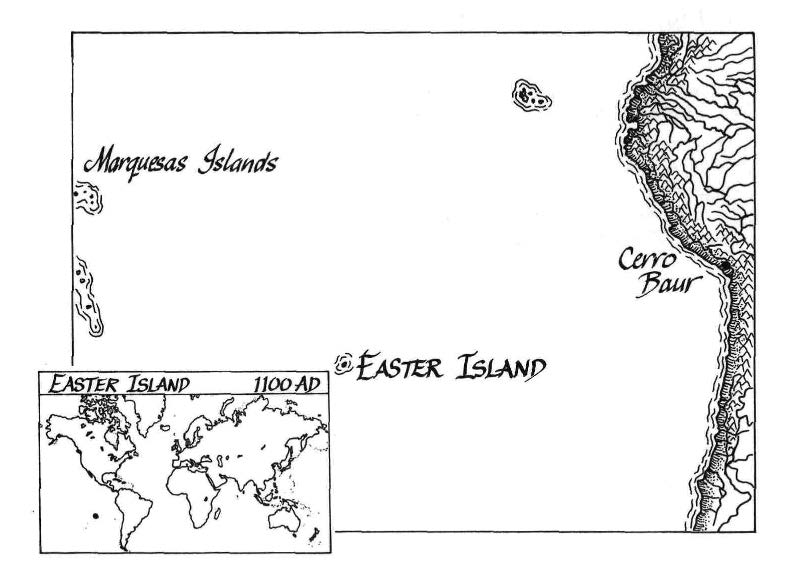

700, and Huari gave way to Chimu, circa 1100, despite climatic disruptions following an El Niño event that destroyed Chimú's capital city at that time; Chimú would in another 400 years give way to the Inca empire that covered present-day Peru and Chile, approximately. Then the coming of the Spaniards would destroy it all.Considerable controversy surrounds the origin and mechanisms of the culture that made and erected the enormous stone statues of Easter Island, in the Pacific Ocean. These statues were up to thirty-two feet tall, weighing as much as thirty tons, and there were about a thousand of them around the island, some still in the quarry. How were they made, how were they moved, and why? For this was not the center of a vast empire. The volcanic island is sixteen miles long and nearly barren, though it once was forested. It is more than a thousand miles from its nearest island neighbors, and almost 2,500 miles from South America, the nearest continent. It was first colonized about

A.D.

300. There is little evidence that it had more than two contacts with any other human population, in the course of 1,500 years. There appear to have been two major population groups: the long ears, who may have had red hair and white skin, and the short ears, who were darker.Some of the mysteries have been solved; some remain. Thor Heyerdahl of

Kon Tiki

fame is amidst the controversy, arguing that the long ears came from South America, and the short ears from Polynesian islands to the west. Others believe that Polynesia was the only origin. There is persuasive evidence on more than one side. Here is the way it may have been, circa

A.D.

1100.This is a triple setting; the male view is on Easter Island, and the female view in the Andes of South America, and the slave view in the Marquesas of Polynesia. The first assumes that a given family traveled to a far isle, the second that it remained on the mainland, and the third that it found an intermediate location.

H

UU kissed Aan and hugged Min. “We will return in five days,” he promised. “You women keep working on your scripting.” For the art of writing was part of the legacy from the old country, and it had to be scrupulously passed along to each new generation of long ears, and kept secret from all others.

“But who will feed us?” Kip asked. He was twelve, and verging on manhood. He was proud to be going on this important mission, but suddenly realized that there could be disadvantages.

“The slaves will provide, as usual.”

“Who will keep you warm at night?” Min asked in her turn. She was ten, and her breasts were showing.

“What do you think girl slaves are for, dummy?” Kip asked her scathingly. Huu and Aan laughed; it was true that the short-ear women were invariably obliging. Unspoken was one of the reasons for this excursion: Kip was of age to have his first sexual experience, for which a slave girl would do, and mothers and sisters were not welcome.

“Yes, maybe that one I taught to dance four years ago,” Huu said, “the last time I was away from your mother.” He would never touch a long-ear woman, of course, but short ears didn't count. Aan did not expect him to sleep alone.

Then he took his wooden flute and his son and set off for the opposite side of the island. He didn't like separating from his wife, even for a few days, but a statue was ready to be moved into place, and it was time to train a new crew. Three long ears would train about fifty slaves, drilling them in precision maneuvers, so as to have them ready. Huu, of course, was the musician; he would handle cadence. The other two would handle directives and discipline. They would train with a dummy block, not risking a real statue, until they not only had it right, they had it without hesitation. The constant drilling would be dull, but there was no alternative. Slaves just weren't reliable unless thoroughly trained and supervised.

He thought about that. When the long ears first decided to erect really significant statues in honor of their gods, they had soon realized that a lot more could be done with less struggle if they had a better source of labor. It had taken years to complete and move the first statue, and there had been injuries and broken stone. So they had organized a slaving expedition, using the same giant reed boats they had used for deep sea fishing, and circled the island to come upon the encampment of short ears by surprise. They had known where they were, because some few short-ear craft had come to the island, blown by a storm, and taken over a section of the island. It had taken time to teach the survivors to speak in the civilized tongue, and to learn their origin. But it was apparent that this was a potential source of labor. So they had gone out and captured the short ears, together with their women and children. They had trained these as suitable slaves, encouraging them to breed so as to increase the work force, and in due course had enough for their purposes.

In fact they had more than enough. The short ears now governed themselves, in their section of the island, and were about to be assigned their first chief of their own number. The truth was that no long ear cared to struggle constantly with the necessary discipline of the unruly slave class, but the change was being presented as a step toward autonomy for the short ears. Their chief would answer to the long ears, but as long as he kept the discipline he would be allowed the privileges of ruling.

They walked south and east and south along the paved road. They were soon clear of the town and in the open country. The forest had been cleared back from the road, and short-ear farmers were tending the fields for their long-ear owners. The ones in the fields ignored the travelers, but those encountered on the road stepped off and bowed until the two long ears were past.

This reminded Kip of something. “Why are their ears so short?”

Huu smiled. “It is not that their are short, but that ours are long. If we did not use earplugs, ours would be as short as theirs.”

“They couldn't be!”

“They could be. It is not nature, but status that gives us the privilege of beautiful ears. Don't you remember the discomfort of your early plugs as they stretched your ears?”

His son nodded, remembering. “But some pain is the price of nobility,” he said, repeating the common sentiment.

“It is indeed,” Huu agreed.

“Tell me how we came here,” Kip said.

It was familiar history, but the boy never tired of hearing it. “The great god Make-Make saw fit to guide King Machaa after he suffered defeat in battle in the homeland. He built a huge reed boat and sailed for two months into the unknown sea, bringing along his wife and children and the families of his supporters. He came here to the Navel of the World, and settled and built the good roads. But he didn't stay. Then Hotu Matua in the homeland lost three great battles against the enemy, and he too had to flee to save his people. He sailed here and settled, and his people govern the island to this day.”

“And my great-grandfather came with him.”

“Yes. My grandfather, with his wife and children. They had been entertaining in Hotu Matua's court, and were invited along. Grandfather Huo thought about it a long time, knowing that his wife preferred to remain in the civilized country, but in the end concluded that it was better to be important entertainers in a new kingdom than routine ones in an old kingdom. So it is that we are here, instead of in the old land.”

“But where did King Machaa's people go?”

“We aren't sure,” Huu admitted. “When my grandfather arrived here, there were roads all across the island, extending from the stone quarry at Rano Raraku. There were many circular stone houses, and houses of other designs, unlike our reed-ship houses. Our people were so busy getting settled at first that they didn't have time for stone building, so we simply turned our ships over and propped them in place and used them for shelters. But the cleared fields were growing back into forest, and only a few people remained, so their stone houses hadn't protected them. Perhaps most of them were hiding in the forest. They spoke of a terrible storm, but it seems it was so long ago that the details of it had been lost. So we don't

know whether the people found better islands and went there, or were lost in the storm.”

“What about Min?”

Kip never tired of that story, either. “We thought we had found all the remaining people and taken them into our own kingdom,” Huu said. “But some hid in caves, and we found them only by chance. Ten years ago, when you were only two, I was exploring for a suitable site for a better home, near the north cliffs, and I heard something. I thought it was an animal, but it was a newborn baby girl. The mother was dead, and the baby was crying. So I picked her up and brought her home, uncertain what else to do, and your mother—well, she was still nursing you, and said she had two breasts, so we kept the baby. That was Min. You see, when your mother birthed you, it was difficult, and though she seemed to recover, she never birthed another baby. I didn't know it was to be that way, but maybe she did, so she was ready to adopt. And I can't say it was wrong, because Min has been a good daughter.”

“She is of the early folk,” Kip said. “That's why she's so spooky.”

“That must be it,” Huu agreed. “The spirits must have safeguarded her, by summoning me there before she died. We buried her mother where she was, and we did not settle there, but every month we take Min there so that her mother's spirit can see that the child is well. And nothing truly bad has happened to us since Min joined us, though there have been some threats.”

“Yes, we almost got banished when King Hotu Matua died.”

“We almost did,” Huu agreed. “But we had no hand in that, and that became clear in due course. In any event, he was very old. He was king for fifty years, ever since our people arrived here. Now we will erect a great statue in his memory, which is why you and I are making this trip.”

“Yes, because we have the instructions written in the script,” Kip said. “That's why we have to read. So we can remember how to make and move the statue.” He had complained about having to read throughout, but now he was proud of his ability.

“And why the short ears don't read,” Huu said. “That knowledge gives us power.”

“Do the spirits protect me too?”

Huu backtracked a bit to catch the reference: the spirits protected Min. “Of that we can't be sure. But we hope so.”

“She has always been there when the spirits helped.”

“We don't really know that the spirits help or hinder us,” Huu reminded him. “They may not care about ordinary people.”

“No, Min can see the spirits,” Kip said.

Huu didn't argue. He had never seen a spirit himself, but there was indeed something about Min. Even the bugs didn't seem to bite her as they did others.

The sun was high when they reached the quarry, and they stopped to eat

their lunch of hardened sweet potato mash before climbing the slope to the quarry. Then they made their way up to the top of the mountain, where it opened out into a bowl-shaped depression. This was the quarry, where they were chipping out yellow stone. The real statue was being carved from the outside edge of the mountain, but the practice block was inside, where there happened to be unneeded stone. A number of short-ear children were crowding close, fascinated by the proceedings. One crew of their elders used hand axes to chip away at the rock beneath the statue. It was evidently tedious, wearing work, but there were many slaves, and when one man had to quit and leave the pit for fresh air, another immediately took his place. The long-ear supervisor kept the work constantly going.

The short ears were already hauling the practice block over the rim, so as to start it sliding down the slope toward the level ground. The long-ear foreman and his assistant were yelling constant orders. It wasn't going well, because the stone was extremely heavy and rough, and kept snagging, so that men with long poles had to pry it up. At the moment it was balking right at the rim.

“This is why they need us,” Huu said. He brought out his flute and approached the foreman. “Music will give them strength,” he said.