She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England Before Elizabeth (45 page)

Read She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England Before Elizabeth Online

Authors: Helen Castor

This time Mortimer, though clearly suspicious, was persuaded to let them go, and once their questioning was over they made

much play of their public departure from the city. The following night, however, they returned without warning or fanfare, silent this time in the darkness. They gathered, Montagu and two dozen others, at the foot of the castle mound, well away from the torchlit gates and armed guards who both protected the king and imprisoned him. Montagu and his men felt their way into a hidden passageway carved into the rock, a secret which they, but not the garrison above, had learned from a sympathetic townsman. Carefully, with weapons in hand, they made their way up the pitch-dark tunnel, a steeply curving slope punctuated with rough stairs, until they emerged into the heart of the castle. As they had arranged, Edward was waiting to meet them. Mortimer and Isabella were surrounded before they knew what was happening, the queen forced back into her bedchamber, Mortimer struggling in shock and fury to draw his sword against his grim-faced assailants, but quickly disarmed and overpowered. After three years, the rule of Isabella and her consort was over.

Mortimer’s fate was not in doubt. The scene had been played out too many times before in the bloodstained years that had been Edward II’s legacy to his kingdom: there was the proclamation of evident guilt – in this case, the murder of the last king and the usurpation of the power of the present one; the sentence of a traitor’s death; then, on 29 November, the scaffold at Tyburn. Just a year earlier, Roger Mortimer had styled himself King Arthur at a tournament of extraordinary magnificence where he sat crowned at a Round Table with Isabella playing Guinevere at his side. Now he was stripped of his clothes and strung up from the gallows, a man hanged like a common thief with a lack of ceremony that mocked the hollow vanity of his former pretensions.

For Isabella, Edward’s coolly executed coup had a very different outcome. She was, after all, his honoured mother, who had been deplorably diverted from her royal duty to her husband and son by Mortimer’s traitorous machinations. For several weeks she was kept under guard at Berkhamsted Castle until it became clear whether or not she would accept this revisionist account of her

actions – but whatever doubt there might have been was quickly dispelled. Isabella had always been a realist, and she had learned at all costs to protect her own interests ever since the day she had stood at the altar as an uncherished bride twenty-two years earlier. We must assume that she mourned for Mortimer, given the evident intensity of their partnership, but she took care to leave no public traces of her grief. By Christmas she had rejoined her son’s court at Windsor Castle, where she remained for the next two years under the most luxurious house arrest Edward could provide. She had formally surrendered her vast estates to her son within a week of Mortimer’s death, and a month later she received in return a grant of

£

3,000 a year to provide for what would be a sumptuously appointed retirement. From 1332 her freedom of movement was gradually restored, and she spent much of her time at Castle Rising – a formidable keep set on top of mighty earthworks a few miles from the sea in north-western Norfolk – where she maintained a stately household and entertained royal visits from her son and his growing family.

She had discovered, in violent and painful fashion, that the will to power could be its own undoing. But perhaps this royal retirement was vindication of a different kind. The deference and luxury that were her due were now hers without question, and she could claim – albeit by a tortuous route – an extraordinary legacy in the person of her son. Edward had inherited his mother’s intelligence, but, more than that, whether by nature or traumatic nurture, he had developed the far-sighted political vision that both his parents had lacked. He understood that the power of his crown lay in law, not tyranny; in loyalty, not fear; and in commanding the consent of his realm, not cowing it into compliance. And by the time Isabella came to face her last illness in 1358, Edward was thirty years into a reign that would earn him an epitaph as ‘the flower of kings past, the pattern for kings to come’.

By then, the bloody events of her political life were distant memories for the sixty-three-year-old queen. That she had found some form of peace with that past seems a likely reading of her

request that she should be buried in the crimson, yellow-lined mantle in which she had been married half a century earlier, with the silver vase containing her husband’s heart interred above her own. And perhaps that reconciliation had more to do with the queenship her marriage had brought her than it did with the man she had married. Isabella had fought for her rights as an anointed queen of England. She had shown – albeit for a brief moment – that female leadership could represent the legitimacy of the crown forcefully enough to depose an anointed king. And her political legacy to her son lay most powerfully in the lessons he learned about the nature of that legitimacy as he watched her do so.

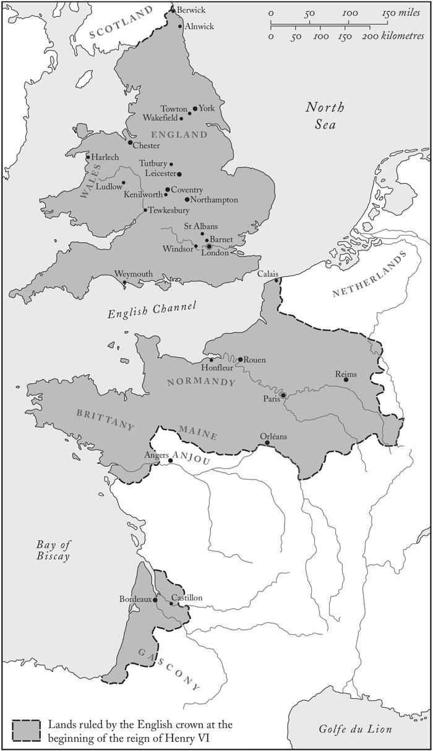

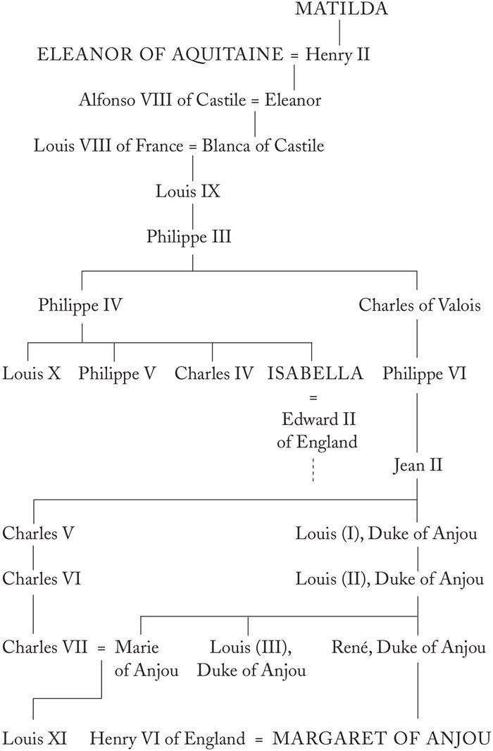

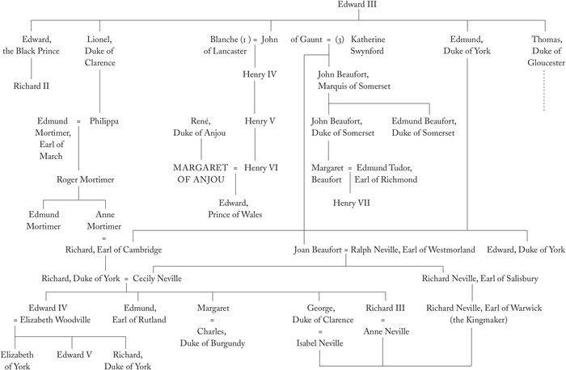

There was one more way in which Isabella continued to shape English politics even after she had accepted her enforced retreat into gilded retirement. Nearly two centuries earlier, Henry II had succeeded to the throne of England as the heir of his remarkable mother Matilda. His descendant Edward III – who had now come into premature possession of the same crown through the intervention of another formidable woman – was hardly likely, therefore, to accept the wholesale exclusion of the female line that had been adopted across the Channel as an expedient rationalisation for the accession of Isabella’s brothers as kings of France. When her last surviving brother, Charles, who had done so much to support her rebellion against her husband, died in 1328, he too left only infant daughters, and the great lords of France hailed his cousin Philippe of Valois as their king. But Edward made it his life’s work to press the claim to the French throne that he inherited through his mother. Not only had Isabella overthrown a king; she had charted England’s course into a war that would last for a hundred years.

A Great and Strong Laboured Woman

1430–1482

Margaret of Anjou was not born to be a queen. It was not that she lacked royal blood flowing through her veins: she was directly descended, after all, from Philippe of Valois, the king who had succeeded to the French throne after the deaths of Isabella’s brothers. Like Isabella herself, she could trace her line back to Eleanor of Aquitaine and the Empress Matilda, and, through her paternal grandmother, she counted the kings of Aragon among her immediate forebears.

But, while her father René was rich in grandly empty titles, he was poor in practical power. Second son of the duke of Anjou, he styled himself duke of Lorraine through his marriage to the duchy’s heiress, and king of Sicily, Naples and Jerusalem through his ambitious grandfather’s accumulation of paper claims to far-flung crowns. But his wife’s right to Lorraine was fiercely contested by the next male heir to the duchy, who inflicted a crushing defeat on René and his army in the summer of 1431. René spent three of the next six years in captivity, only securing his eventual freedom through the payment of a punishing ransom. On his release he set sail for Naples, hoping to win that kingdom in place of the dukedom he had lost, but, four years of fighting later, a disconsolate René was driven out of Italy for good. After the death of his elder brother, he was now duke of Anjou and count of Provence, but the resources he had expended in pursuit of his hollow crowns had left him scarcely able to maintain the state of those remaining titles.

Margaret, meanwhile, had been left behind in France along with the rest of the duke’s young family, at first under the supervision of their mother Isabelle of Lorraine, and then – from 1435,

when Isabelle made her way to Naples as an advance guard for her imprisoned husband’s claims there – of their formidable grandmother, Yolanda of Aragon. By the time René eventually returned home in 1442, twelve-year-old Margaret had learned an extended lesson in how capable a woman could be when called upon to wield authority for an absent husband or son. She had also discovered that neither power nor wealth could be taken for granted. Rights, it seemed, had to be fought for, possession asserted rather than assumed.

Still, the observation that the wearing of a crown did not automatically confer control of a kingdom seemed unlikely to bear directly on Margaret’s own experiences. Her marriage was already much discussed, but none of her prospective suitors – the son of the count of St Pol, and successively the son and the nephew of the duke of Burgundy, powerful though they might be – offered her a throne. Nor did the return of her thwarted and impoverished father, a king in insubstantial name only, promise a radical shift in her destiny. But it came all the same, thanks to the war between England and France that had been precipitated by Isabella’s claim to the French crown a hundred years before.

Before her death in 1358, Isabella had had the satisfaction of seeing her son, Edward III, win great victories at Crécy and Poitiers in pursuit of the throne that, he believed, she had bequeathed him. That claim was fiercely disputed by the French, who now elaborated the pragmatic precedent by which Isabella’s brothers had become kings of France in place of their infant nieces into a freshly minted ‘ancient’ tradition, the ‘Salic Law’, which formally prohibited female heirs from either taking, or transmitting rights to, the crown. But despite this French resistance, Edward’s military talents were enough to regain control of the great duchy of Aquitaine, restored almost to the glories of its full extent under its duchess Eleanor centuries earlier.

Edward’s triumphs, however, did not last. Less than thirty years after his death, English politics imploded spectacularly under the strain of the paranoid megalomania of his grandson, Richard II.

Richard lost his throne and his life to his cousin, Henry of Lancaster, and the French were full of scorn when Henry’s son, Henry V, sought to renew the English claim to their kingdom. But their jeers fell silent when this stern young man – scarred by a crossbow bolt taken full in the face amid the maelstrom of battle at the age of just sixteen – crushed the flower of French chivalry into the mud at Agincourt. He proceeded, town by town and castle by castle, to conquer Normandy for the first time since it had slipped through King John’s fingers two hundred years earlier. By 1420 Henry was in a position to dictate terms to his bruised and battered opponents, and those terms were that he should marry the French king’s daughter Catherine and be recognised as heir to the French throne.