Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher (25 page)

Read Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

If the first two volumes of

The North American Indian

had been pastoral and somewhat painterly, the next two books, on the Sioux and the

Crow, would be darker, with more of a documentary look. Curtis felt the burden of

a nation’s cherished narrative and the reputation of a man considered “a light to

all youth of America,” in Roosevelt’s words. As the Curtis team went through the story

cautiously day by day, one side would play prosecutor, the other defender.

“Dear Meany: . . . Has there been anything published on the fact that Custer, from

the highest viewpoint of the region, watched Reno’s charge, battle and defeat?”

That was the crux of Curtis’s major finding, and by midfall he felt he was on solid

enough ground to start circulating the story. Curtis relied on Meany’s counsel, and

his writing and research, to help him through this section. “As far as I have read

nothing of this nature has ever been published,” Curtis continued. “It puts an entirely

new light on the entire Custer fight.” It did indeed. But the supportive Meany knew

that his friend was playing with historical fire, and warned him of the consequences.

“This is not a pipe dream on my part,” wrote Curtis. “I have ridden the battlefield

from end to end, back and forth from every important point on it, noting carefully

the time of such rides.” A month later, he wrote again, asking Meany to find transcripts

of the military inquest. He also indicated that he would not be home for Christmas.

In another note to the professor, seeking to counter doubts from friends in Seattle

and New York, Curtis showed that his confidence had not dimmed:

“If you hear anyone say that I am not to succeed, tell [them] they don’t know me.”

By early January, the Curtis entourage was making great progress and showing few signs

of cabin fever. “The work on the Sioux volume has gone like a whirlwind, and consequently

happiness reigns among us,” he wrote Meany. The next letter, after a lapse in the

professor’s response, was addressed to Mrs. Meany. “If that tall, good-natured husband

of yours is still wandering around the face of the earth will you be good enough to

drop me a word, and let me know when you expect him home?” Finally, early February:

“Our work on the Sioux volume is practically complete.”

Curtis took a break to travel to New York, again to grovel for subscriptions and

to update Belle da Costa Greene on what he was doing with her boss’s money. While

there, he gave an interview to the

New York Herald,

offering a preview of his findings. After conducting his exhaustive examination,

he had something extraordinary to share: when he published the next volume of

The North American Indian,

he explained, it would be there for all the world to see.

SAYS CUSTER THREW MEN’S LIVES AWAY

The headline was the least of it. The story reported that Curtis had proof that Custer

“had unnecessarily sacrificed the lives of his soldiers to further his personal end,”

and that he could have won the battle with little loss of life. “I know it is unpopular

to criticize a military commander,” Curtis said, but the Indians who were with him

felt that his judgment was flawed. “When the wise old Indian warriors that were in

this fight are asked what they think of Custer’s course in the battle, they point

to their heads and say, ‘He must have been wrong up here.’”

The article caused a furor. Two officers of the Seventh Cavalry said it was a slander

against an American hero and the honor of their fallen comrades. Libbie Custer flew

into high dudgeon; she went to work trying to prevent Curtis’s version from ever being

published. She leaned on her friends in high places, starting with the president.

She battered Gifford Pinchot. How could he do so much to promote this Curtis man,

she complained. She demanded that the forester quash the rewrite of the last day of

her beloved “Auty.” Though Pinchot was circumspect, he did the widow Custer’s bidding.

The newly named Custer National Forest would be unveiled in 1908, and he did not want

a controversy hanging over it. He wrote Curtis of his concerns. The photographer promptly

replied with an offer to send Pinchot all the material backing his conclusions.

Sensing that the knives of the Custer historical cabal were getting close enough to

hurt him, Curtis tried to bring President Roosevelt around to his side. But first

he went to the military, sending a sheaf of notes to three longtime army officers

and to Charles A. Woodruff, a recently retired brigadier general who had arrived at

the Little Bighorn days after the battle. Woodruff agreed to walk the battlefield

with Curtis. After spending several days with him, the general urged Curtis to write

a complete report and send it to the president. On the officer’s advice Curtis explained

his investigative foray for the highest literary critic in the land. “I have ridden

with our blood all tingling with the swing of our horses as we galloped across the

plains,” he wrote, appealing to the adventurer-historian in Roosevelt. This was the

way of the western man of letters—boots muddy, scholarship by walking around. The

reply from the White House was written on April 8, 1908:

My Dear Mr. Curtis:

I have read those papers through with great interest, and after reading them, I am

uncertain as to what is the best course to advise. I never heard of the three Crow

scouts that you mention, and did not know that they were with Custer. I need not say

to you that writing over thirty years after an event it is necessary to be exceedingly

cautious about relying upon the memory of any man, Indian or white. Such a space of

time is a great breeder of myths. Apparently you are inclined to the theory that Custer

looked on but a short distance away at the butchery of Reno’s men, and let it take

place, hoping to gain great glory for himself afterward. Such a theory is wildly improbable.

Of course, human nature is so queer that it is hard to say that anything is impossible,

but this theory makes Custer out to be both a traitor and a fool. He would have gained

just as much glory by galloping down to snatch victory from defeat after Reno was

thoroughly routed . . .

Curtis was crushed. It was the first time the president had let him down. And with

each word from Roosevelt, the story that had taken three years to construct lost a

stone or two of its foundation, until most of it lay in ruins. Roosevelt was not saying

he doubted Curtis’s material. He had no facts to refute what Curtis had found. But

logic made it all hard to believe.

Wildly improbable.

If Curtis was defiant after reading the letter—his usual initial impulse—those two

words could not be easily banished from his mind. With his meticulous reconstruction

of the battle, Curtis had persuasive evidence to win over the educated cynics, those

who never believed that the boy wonder with the camera was mining an untouched vein

of valuable history. He felt, at once, that

The North American Indian

was deeply wounded, and the doubts about his Custer revisionism might kill it altogether.

His careful nurturing of friendships, pacts and deals with the most powerful people

in the country, the eastern men who had made his life quest possible, was mortgaged

to particular conditions, some of them never written down. Curtis could plow ahead—Roosevelt,

Pinchot and all of Libbie Custer’s connections be damned—but that could mean the end

of The Cause, as Curtis now called his work.

Wildly improbable? Wildly improbable!

“I am beginning to believe that nothing is quite so uncertain as facts,” Curtis wrote

an army colonel who had encouraged his fresh examination of the Little Bighorn. It

was three weeks after Roosevelt’s note. A few months later, in a letter to Meany,

Curtis indicated that the white flag was flying over the cabin in Montana. “I have

been very guarded, and while giving a great deal of new and interesting information,

I have said nothing that can be considered a criticism of Custer.” The story of the

Crow scouts, the many notes and depositions from White Man Runs Him, the many translations

from Upshaw, the detailed and seemingly indisputable narrative helped along by Sioux

and Cheyenne who’d participated in the battle, the measured fact-checking by Meany

and Myers, the topographic maps and time-of-day placements—all were bundled up and

locked away, the scholarship never to find a home between covers of

The North American Indian.

The story of Custer invading a sovereign nation, the rise and fall of the Sioux—“the

limitless Plains theirs to roam”—a buffalo and warrior culture conquered by a ruthlessly

superior one, came out in Volume III. Curtis wrote clear and passionate prose, and

was often prescient. On Wounded Knee, the last real clash between the worlds, he said,

“To the future historian if not to our own, the so-called Battle of Wounded Knee will

appear to have been little less than a massacre.” But that was as far as he went.

A battlefield map of Little Bighorn was published, showing contour lines. A careful

reader could perhaps discern what Curtis had found; almost nobody did until much later.

Curtis printed only one of his revelations, though it was certainly not enough to

force citizens to look twice at statues of Custer in their town squares:

“Custer made no attack,” he concluded in Volume III, “the whole movement being a

retreat.”

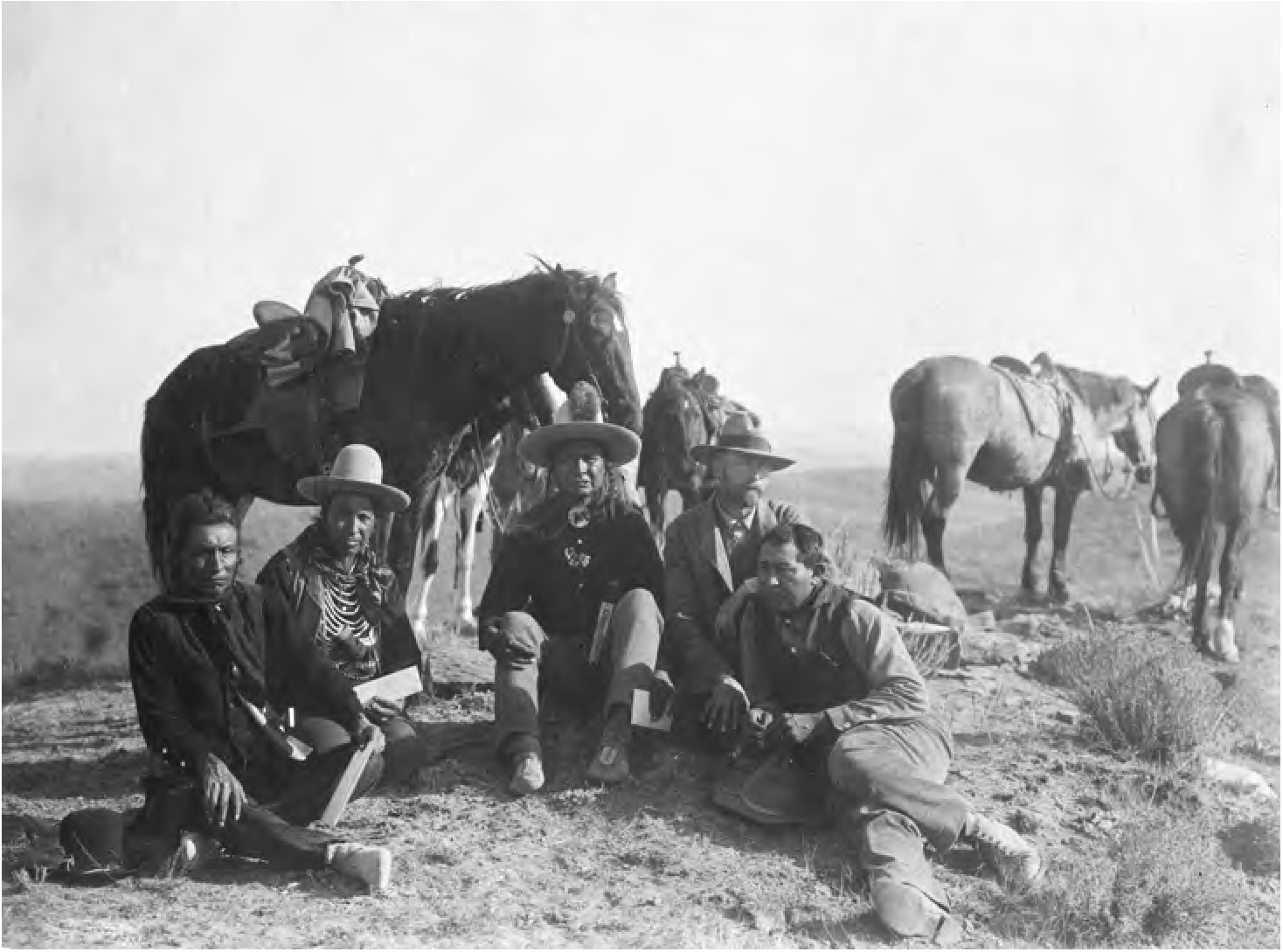

1908. Curtis went back several times to the site of the Battle of the Little Bighorn,

trying to uncover the true story of the worst loss by the American army in the Indian

wars. Here he faces the camera himself, with his native guides. Left to right: Goes

Ahead, Hairy Moccasins, White Man Runs Him, Curtis and his aide Alexander Upshaw.

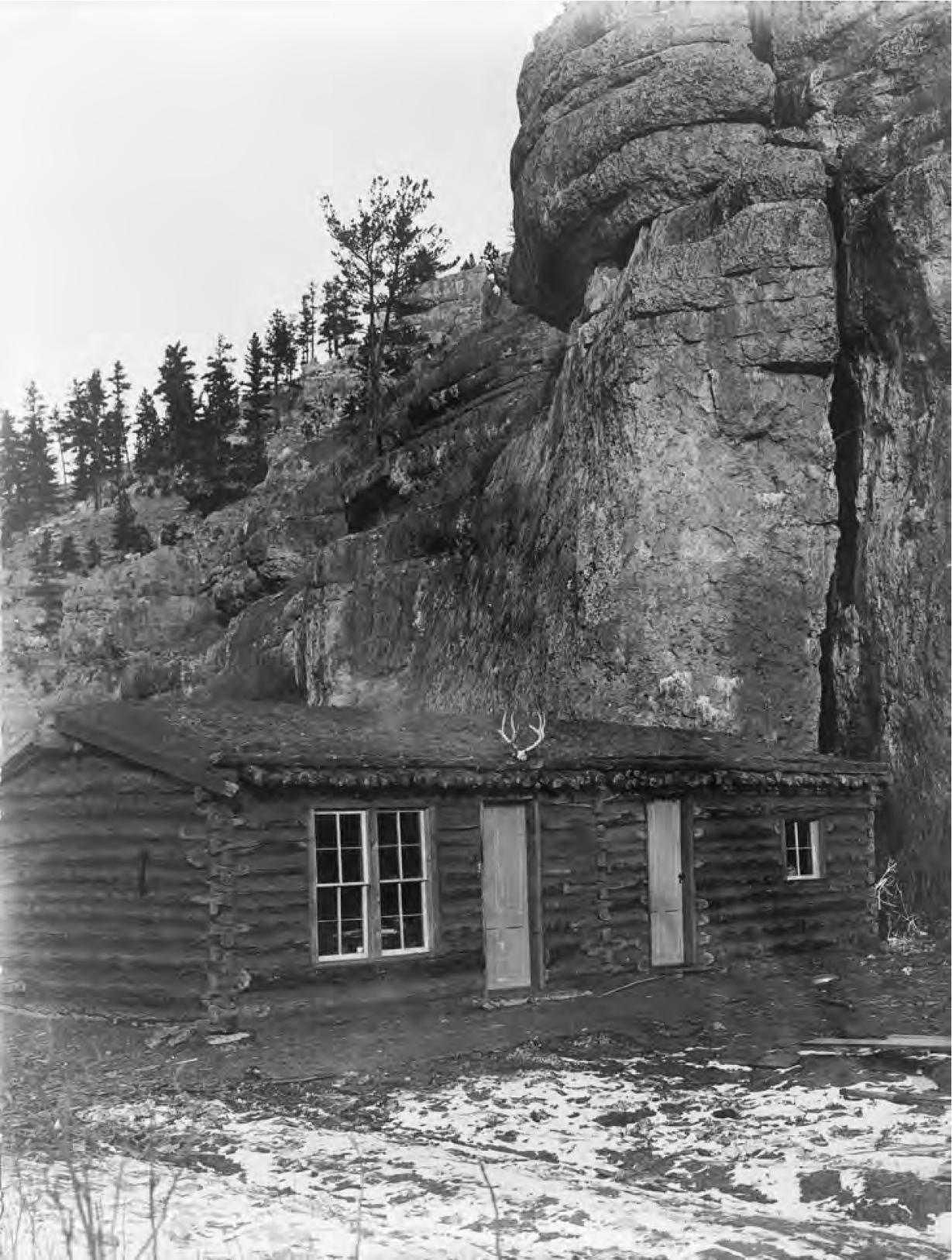

1908. Curtis tried to record scenes of the hard life of a winter on the northern

plains.

Upshaw and others holed up here while putting together the Little Bighorn story. They

often debated late into the night.

1908–1909

F

OR NEARLY FOUR YEARS

, Curtis saw more of Alexander Upshaw and natives of the northern plains than he did

of Clara and Seattle. And what he saw in their last months together was a troubled

man whose education had opened his eyes to the impossibility of straddling two worlds.

Upshaw spent a typical workday helping Curtis re-create a time when the Crow had their

own religion, dress and economy, when nobody called them inferior or immoral. And

then he went home at night to a family on a reservation where nearly everything from

that past was being scrubbed from the land. Through the seasons, Upshaw was with Curtis

on horseback under a searing sun, in snowstorms that blotted out the Montana sky,

and in a tent at night until the last candle burned out. The translator roamed all

over Indian country with his boss, and had ideas on narrative, picture themes and

the many qualities of Apsaroke women. Curtis called him “my great and loyal friend.”

Upshaw returned the compliment: the Shadow Catcher, he said, was “a fine man.” Curtis

paid him $100 a month—that is, when he paid him at all—far more than any of the hundreds

of other Indians he’d employed over the years.