Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher (44 page)

Read Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

Curtis had reached that stage in life when the social rituals are not weddings or

baptisms, but funerals and burials. His younger brother Asahel died in 1941, of a

heart attack, at the age of sixty-six. Over the course of his career, he probably

took more pictures than did Edward. He shot everything: the first skyscraper in Seattle,

the Smith Tower, which for much of the twentieth century was the tallest building

in the West; the earth-moving projects that left spires of the original city around

as engineers tried to make a flat metropolis; Indians on downtown streets and athletes

on the field; dams, schools, office buildings, ships, trains and roads. His camera

had a utilitarian eye, without any weakness for sentimentality. He was best known

for his outdoor work, as a climber and a conservationist. With Meany—a friend to both

Curtis brothers—he guided the Mountaineers through decades of growth, and was the

first person to scale many of the iconic peaks in the Northwest, including Mount Shuksan

in the North Cascades. He carried his feud with Edward to the end: the brothers had

not spoken to each other in over forty years. His ashes were placed at the site of

the newly named Asahel Curtis Memorial Grove in Snoqualmie National Forest, east of

Seattle. When a son, Asahel Curtis Jr., was asked in 1981 about the brothers’ estrangement,

he said only that it was “ridiculous.” And when the same question was put to Jim Graybill

in 2012, the sole surviving grandchild of Edward hinted at a shameful story, saying,

“I just can’t discuss it.”

Curtis moved to a farm near Whittier, California, owned by Beth and her husband.

There, he talked to the chickens, grew avocados and oranges. He was bored and restless,

in need of an adventure. He spent hours preparing large meals at family gatherings,

where he took issue with anyone who did not see the greatness in his cuisine. Shortly

before Harriet Leitch contacted him, Curtis moved back to the Los Angeles.

Near the end of 1948, Curtis started sending memories to the Seattle librarian. While

rummaging through a trunk at his daughter’s home, he’d come upon a seventy-four-page

memoir he’d written decades before and never published. He spent all afternoon with

this account of his adventures—twenty thousand words. “I began reading it at once

and found it so interesting that I did not put it down till the final word was reached.”

He sent a copy to Leitch, and he also shipped her the major reviews of

The North American Indian,

from all over the world. These clippings, he wrote, should give her a sense of “the

considerable importance of the work.” He said he’d received more than two hundred

notices, all favorable but one—a critic who disagreed with Curtis’s revisionist account

of the Nez Perce War. (Later historians sided with Curtis.) And he urged Leitch to

spend some time with a single book from the series, to pick one at random: “Look at

but one volume to see what a task it was to collect such a vast number of words of

assorted dialects.” Along the West Coast alone, “we recorded more root languages than

exist on the rest of the globe. In several cases we collected the vocabulary from

the last living man knowing the words of a language. To me, that is a dramatic statement.”

Leitch was impressed. And she was “thrilled,” she said, to read the autobiographical

sketch. She knew his reputation as a photographer, but the anthropological work, the

salvage job of languages from the scrap heap of time—that was a revelation. Countless

words that had bounced around pockets of the Great Plains or dwelled in hamlets along

the Pacific shore lived—still—because Curtis had taken his “magic box,” the cylindrical

recorder, along with him when he went to Indian country. Also, he had preserved more

than ten thousand songs. And yet, for all the stories, myths, tribal narratives and

languages Curtis had saved for the ages, it was curious, the librarian suggested,

that the photographer had never told his own story. Why no memoir beyond the sketch

he’d sent her? Surely his dashing and perilous life, the unstoppable young man in

his Abercrombie and Fitch, the self-educated scholar who made significant breakthroughs

in ethnology and anthropology among overlooked nations, his proximity to J. P. Morgan

and Theodore Roosevelt and E. H. Harriman and Gifford Pinchot, his campfire tales

from Chief Joseph and Geronimo and the last of the mighty Sioux warriors—surely there

was a great, sweeping story to be told.

Curtis had indeed started to record his personal history, sitting for days with his

children so that they might have something for posterity. But now he lacked the oomph;

the project had been shelved. “Among the foremost why nots, I am not in physical or

financial condition to attempt so large an undertaking,” he wrote. Plus, he’d heard

a familiar refrain from the gatekeepers of American letters in New York: “A publisher

told me there is but a limited market for books dealing with Indian subjects.”

He spent Christmas with Beth—a “delightful” holiday. With the dawn of the new year

of 1949, Curtis started to regain some energy. The stories spilled out of him, in

letters mailed up the coast to Harriet Leitch. He recalled his father, the sickly

preacher and Civil War private, who died when Curtis was fourteen, leaving him to

become “the main support of our family.” He told about his accidental avocation, how

he took up photography only after a severe back injury prevented him from making a

living as a brickmaker or in the lumberyards. He described for Leitch his first Indian

picture, Angeline—“I paid the Princess a dollar for each picture I made. This seemed

to please her greatly.” He gloried in long accounts of Mount Rainier climbs. He talked

about his work habits. “It’s safe to say that in the last fifty years I have averaged

sixteen hours a day, seven days a week,” he wrote. “Following the Indian form of naming

men, I would be termed, The Man Who Never Took Time To Play.”

Their correspondence carried through another death, in April of 1949—William Myers,

the writing talent behind

The North American Indian.

He had married a second time and moved to Petaluma, north of San Francisco, where

he managed a small motel. He was seventy-five at life’s end, six years younger than

Curtis. A routine obituary in the

Santa Rosa Press Democrat

did not bring up Edward Curtis or the fact that Myers had spent the majority of his

adult life doing first-rate field anthropology and writing about it for the most detailed

study ever done of native people of North America. He was described as a motel manager,

retired and childless.

Through the summer and into the fall, Curtis worked away at the book he was building,

tentatively titled

The Lure of Gold.

The walls of his tiny apartment were plastered with notes in his unreadable scratch.

“I’m busy with The Lure of Gold,” he wrote Leitch in October, brushing off a fresh

round of questions from her about his Indian work. By the spring of 1950, Curtis was

almost manic with energy, again crediting his Oregon tea. “My health is improving,

and now I look forward to celebrating my 99th birthday.” He parried back dozens of

answers: on the reburial of Chief Joseph, on the good work of Professor Meany, and

how together they discovered the true story of the Nez Perce, a pattern that followed

with the Custer revision. How did he do it? “I didn’t get my information from the

white man.”

Near the end of 1950, Curtis turned cranky. If it wasn’t “that damn television” blaring

in a neighbor’s apartment, it was his arthritis, which on many days prevented him

from holding a pen, let alone set it to paper. On such occasions, he said his “pen

died a sudden death.” A few days before Christmas in that year, Belle da Costa Greene

passed away in New York City, at the age of sixty-six. Her sway over the Morgan Library

had lasted forty-three years, until her retirement in 1948. She never married, and

took many of her secrets with her to the grave: she had burned her personal papers

shortly before her death.

Curtis limped into 1951, the late-stage burst of energy having dissipated. “I am

still housebound,” he wrote, “living the life of a hermit.” He wished for simple things—a

stroll to the store to buy his own food, a taste of fresh strawberries, an afternoon

on a park bench. “It’s Hell when you can’t go to the market and get what you want.”

The apartment was suffocating him. He started calling himself Old Man Curtis, and

his handwriting became illegible. In July of 1951, he was forced by finances to move

to an even smaller apartment, at 8550 Burton Way, in Beverly Hills. He called it “the

most discouraging place I have ever tried to live in.” Through that year, Curtis deteriorated

further, though he responded to Harriet Leitch’s prodding in brilliant flashes here

and there, with some of his sharpest recollections. He told stories of the Harriman

expedition to Alaska in 1899 and of meeting J. P. Morgan for the first time. Teddy

Roosevelt was fondly recalled—manly, loyal, robust, a mind as kinetic as that of Curtis

himself. Leitch got an account of the Sun Dance with the Piegan and the Snake Dance

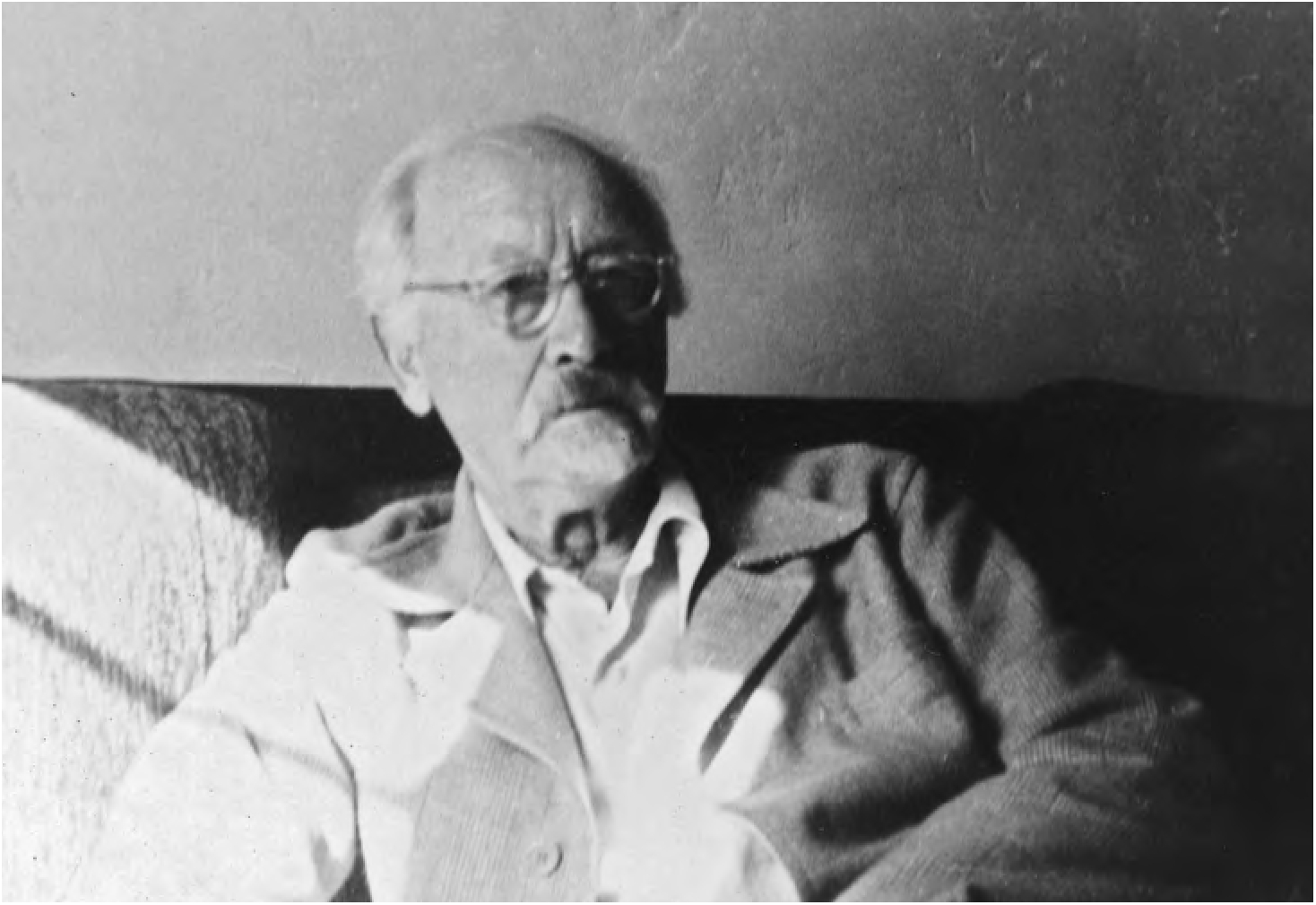

with the Hopi. On February 16, his eighty-third birthday, Curtis posed for a formal

portrait. He still had the Vandyke beard and wore his hat at an angle—no doddering

old fool, this man.

Finally, the pace of memory-collecting slowed to a crawl and the words refused to

come. Curtis complained about his “scrambled life,” a blur of disconnected images

and places, all at the frenzied behest of The Cause. At night, in his dreams, he revisited

the Hopi and Apache, the Sky City of Acoma, the Grand Canyon cellar of the Havasupai

and the sublime isolation of Nunivak Island. Had he really been to these places? While

asleep, he would construct “whole paragraphs in Indian words,” he recalled. These

images came at random, as with any dream; it was his only real escape from the prison

on Burton Way. He was desperate for a new home. “I have to get away from the smog.”

As it became more difficult to summon his past, he apologized.

“This is a bum letter,” he wrote Leitch on July 3, 1951. “I will try to do better

in the future.”

“I am nearly blind,” he wrote on August 4. Now, even the carrots had failed him.

It was the last letter from an epic gatherer of words and pictures. He had written

Leitch twenty-three times over nearly four years of correspondence.

On October 19, 1952, Curtis died of a heart attack. He was eighty-four. It was a national

curse, it seemed once again, to take as a life task the challenge of trying to capture

in illustrated form a significant part of the American story. The Indian painter George

Catlin had died broke and forgotten. Mathew Brady, the Civil War photographer who

gave up his prosperous portrait business to become a pioneer of photojournalism, spent

his last days in a dingy rooming house, alone and penniless. Curtis took his final

breath in a home not much larger than the tent he used to set up on the floor of Canyon

de Chelly.

E. S. CURTIS, INDIAN-LIFE HISTORIAN, DIES

The

Seattle Times,

which had shared his glory days as if they were the paper’s own, dismissed Curtis

with a six-paragraph obituary that ran on page 33. As brief as it was, the notice

in his hometown paper contained a number of inaccuracies, including a claim that Curtis

was “Seattle’s first commercial photographer” and that he had gone on the Harriman

expedition a full seven years before he ever met Harriman. The

New York Times

had drafted a lengthy life story when it appeared that Curtis was lost at sea off

the Queen Charlotte Islands back in 1914. When he actually died, the paper ran an

obituary of seventy-six words, and never directly mentioned

The North American Indian.

He was called an Indian authority who also did some photography. The obituary said

nothing of the languages he recorded and preserved, the biographies he wrote of Indians

still alive, the groundbreaking work he did in cinema. Some years later, the

Times

arranged with the collector Christopher Cardozo to sell “limited edition” lithographs

of Curtis pictures, including some of the most iconic—

At the Old Well of Acoma, An Oasis in the Badlands, Chief Joseph

—and thus began a long, lucrative business offering the Indian pictures of the Shadow

Catcher to connoisseurs around the globe.

Collectors were always asking if there was anything still to surface from the Curtis

estate. No, Beth insisted: her father had left this world as he’d entered it, without

a single possession to his name. That is, with one exception, unknown to outsiders,

perhaps even to the House of Morgan, and certainly to the creditors who had chased

him from one century to the next. Curtis had held on to a single set of

The North American Indian,

the twenty volumes taking up five feet of shelf space in the tiny apartment on Burton

Way. Though he was alone at death, and friendless, not a single person in those books

was a stranger to him.

years in southern California. He dreamed of launching another project, struggled to

write a memoir and spent many days talking to chickens and tending avocado trees.