Skywalker--Close Encounters on the Appalachian Trail (41 page)

Read Skywalker--Close Encounters on the Appalachian Trail Online

Authors: Bill Walker

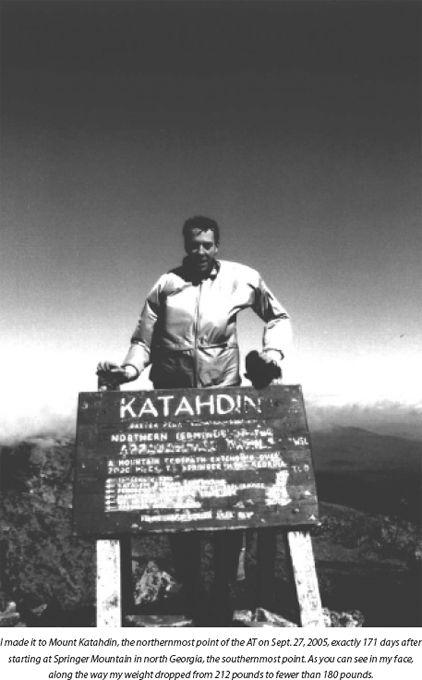

Howling wind and rain were back with a vengeance. At two-thirty in the afternoon we all made it to the Carl Newhall Shelter, but like an army, we appeared stalled out in the mud and fog. Getting over exposed White Cap Mountain was going to be impossible this day. And quickly it became clear it was going to be a miserable afternoon and evening. It was cool and damp, and I knew how my 6’11,” now less-than-180-pound physique would respond. Further, Stitch was again carping and snapping at Foamer.

When Cackles said, “There’s a campsite one and eight-tenths miles up the mountain. We’re going to head on,” she piqued my interest.

“I’ll tag along, if it’s okay,” I said. Moving on would at least keep my body temperature up for the next ninety minutes. Off I went, tagging behind the Joy Machine. Cackles, as noted before, was the master of conversation while trekking up steep climbs. I just tried to keep up and not get lost in these nether regions.

We arrived at a wide open area, which we presumed to be the Sidney Tappan Campsite. Three guys had their tents set up right in the middle of the AT. “There has to be more to this campsite than this clearing,” Box- of Fun said, looking around. We wandered over to the nearby camping area to inspect the terrain. “It all looks a little rocky,” Box-of-Fun said, examining them.

“The clearing is cool with me,” Cackles said, and I followed them out to the clearing. We put the tents up. The rain had lightened up, but we were completely exposed to a powerful, forest-shaking wind.

The Joy Machine had the good sense to cook dinner and then get in their tents for the evening by six o’clock. I, on the other hand, dithered in the dark. I even went on a sightseeing tour to the privy, despite my anemic headlamp battery. When I finally did get in my tent it was probably about eight o’clock, and I had already begun feeling chilled. Nevertheless, I was able to get comfortable until about midnight. At that time I exited my tent to relieve myself. But upon returning a strong draft began to dominate my thoughts in the “warmth” of my tent.

Over the next few hours I tried everything I could possibly conjure up to get warm, but to no avail. Not even the emergency blanket worked, as I thrashed around as if fighting a wild animal. I’d made a huge blunder in not camping over in the less-exposed trees, or down the mountain with Stitch and Foamer. The temperature was probably no less than forty degrees, but my muscles became increasingly tense. I just didn’t have the body fat to stay warm in these high winds. I wondered if I would even have the energy to make it over White Cap Mountain the following day.

As I lay there listening to one roaring gust of wind after another, paranoia began to set in. When I heard some stirring in the guy’s tent I yelled over, “What time is it?”

When one responded “two-thirty,” my heart sank. That meant I had three or four more hours of maximum physical exertion and eerie mental torment to endure before daybreak.

Then I remembered the

privy

. In my sightseeing tour the previous night I had noticed it wasn’t one of those open-air privies. It had four sides. That made it the most valuable piece of real estate in the Hundred-Mile Wilderness.

Off I went down a dark side trail and soon I came upon the privy. It wasn’t big. I opened the door and sat on the toilet seat. It wasn’t much bigger than an airplane bathroom, but seemed okay. I sat in there listening to the howling wind bouncing off the privy walls and began to feel more relaxed. In fact, I was marveling at my genius for improvisation during a crisis.

It was so good that I decided to go retrieve my sleeping bag and make a night of it in there. Again, I stumbled back to my tent, and a few minutes later I was back in the privy, with my sleeping bag wrapped around me.

My enthusiasm waned a bit when multiple efforts to find a sleeping position failed. It waned even more when a strong ammonia-like smell hit me. I wondered if I was getting paranoiad again or whether I was getting high off the smell. My mind started to wander, when suddenly, thank God, I came to in a cold sweat. I burst out of the privy swaying. It was all I could muster out of my shaky legs to stagger with my sleeping bag in the dark back to my tent. Fortunately, when I dove back into my tent my body had been so exercised by the entire misadventure that I was warmer and the crisis passed.

At first light when Box-of-Fun poked her head out of the tent, yawning, I asked, “Were ya’ll able to sleep out here exposed to those high winds?”

“Yeah,” she answered, confused as to the basis of the question.

“Another rookie mistake on my part,” I then explained.

“You and your rookie mistakes, Skywalker,” Cackles reprimanded me acidly. “You’ve gone all the way from Georgia to Maine. That excuse is getting old.” She obviously had a point. However anyone who has unsuccessfully tried everything in their human power to get warm for several hours knows just how desperate the feeling is. Desperate people do desperate things.

Finally, I got moving, but the usual morning adrenaline lasted no more than a mile, the least ever. The climb up White Cap, which in typical Maine fashion had multiple ascents, was punishing. I was stopping every fifteen minutes in my debilitated state. “Ha, Skywalker,” came a vaguely familiar voice from my rear. Looking behind me I saw Buffet and Goat for the first time in three months. They were a late-fiftyish couple who had started in late March and that I had come upon in central Virginia. After hiking with them for a couple days I had gone ahead of them, presumably for good.

But it was utterly impossible to guess whether a thru-hiker wanna-be could make it all the way or not. It reminded of my friend who worked in a nursing home who said that the every-day banter of employees included everyone guessing which patient was going to be the next to die. “It was uncanny how wrong we were,” he related. “Some patients you were sure were goners would find something deep within and fight back to live for years. Others would just fall off a cliff and be gone in a wink.” The same phenomenon was at work here on the AT in a less final way.

“This is bad for morale,” I said to Buffet and Goat. “People I passed are all now blowing past me.”

“We’ve enjoyed reading your journal entries,” Buffet laughed. “Especially the one at the Halfway Store in Pennsylvania when you wrote one word: ‘Uncle.”

“Now I remember,” I said. “You’re New Hampshirites. You turn out hikers the way Brazil turns out soccer players.” They laughed and continued past me, to stay ahead for good.

White Cap Mountain’s frosty peak had a majestic view of uncharted lakes and the dense Maine autumn forest below. But I skipped across the granite summit in a hurry because of the powerful draft and my all-important focus on maintaining my sense of direction while above treeline. After three steep miles of rocky descent the trail leveled off.

An ATC map showed unprecedented topography. For the next sixty miles the trail is flat as a landing strip, until abruptly interrupted by the gigantic forty-two hundred foot climb up Mount Katahdin. Despite bone-weary fatigue, my morale had picked up dramatically from my awful night.

Right as the sun came out in the afternoon I found an ice-cold spring just off the trail near Mountain View Pond. That gave me a disproportionate boost, and I was able to rock-hop over the Pleasant River. Then the trail became a straightaway and I put the speedometer on maximum speed (three mph). Everything was perfect on this late-September day in the northern Maine wilderness. I was now an odds-on favorite to complete this dreamlike journey.

When I got to the shelter I told Foamer about the previous night’s privy incident. “Boy, it’s a good thing you didn’t do that back in Georgia when people were getting trail names,” he cracked. “No telling what kind of name you might have ended up with.”

I

wandered upstream and pitched my tent along the brook. In the morning at the shelter I saw where Stitch had once again caught ten or twenty mice overnight with his mouse trap and laid them on a stump for hiker viewing. As vegetarians, the Joy Machine didn’t normally approve of such things, but they made an exception in the case of rodents occupying shelters.

The next couple days this hiker convoy moved through the last part of the Wilderness at an increased clip. Periodically, we would stop at one of Maine’s seemingly endless, large, shimmering lakes with names like Potawadjos, Pemsdumcock, Nahmakanta, or my favorite, Mooselookmeguntic, to take in glimpses of the imposing fa ade of Mount Katahdin. Unlike the first glimpse of it one hundred fifty miles back from the ski summit house, it was quite clear what we were gazing upon.

In one shelter register Paparazzi captured my thoughts well with the following entry:

Rainbow Stream Lean-To—mile 2,151

5-5-05

: What is it going to be like living in a world where people don’t argue incessantly about Warren Doyle, Baltimore Jack, and Wingfoot?—

Paparazzi

Finally, we got to Abol Campground and the end of the 100 Mile Wilderness.

I walked alone the next day along a stream running away from the mountain with the heavy mass of Katahdin looming ever larger. The forest was approaching full-golden there in late September. The blazes ran out on this side of the rushing stream, and I wandered around confused. Finally, I spotted one on the stream’s far side and pondered how to get over. At last I found a log-and-rock path across and looked downstream at the white rapids of this mountain stream and the golden autumn forest. I had never seen anything like Maine. It’s a jewel. It was really coming home that this whole new, intense way of life was coming to an end, and I wondered how in the world I would come down from it.

I followed the serpentine trail and entered Katahdin Stream Campground. At the ranger station they told me there was a special campsite for thru-hikers, called the Birches, for which I paid eight dollars. “What’s your weather forecast for tomorrow?” I asked.

“Not at all good,” he said ominously. “The hurricane-related weather is expected to get here tonight.”

A group of hikers arrived right after me and said they were hitchhiking to Millinocket, twenty-seven miles away.

“Why not just do it tomorrow, after summiting?” I asked.

“Have you heard tomorrow’s weather forecast?” one said, looking me in the eye.

This looked like one of those places, such as Mount Washington, where weather could be an especially critical factor. I thought of Paddy O’s remarks back in New York that, “I owe that mountain more than I could ever repay.”