Small Man in a Book (11 page)

Read Small Man in a Book Online

Authors: Rob Brydon

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

Born to Jump.

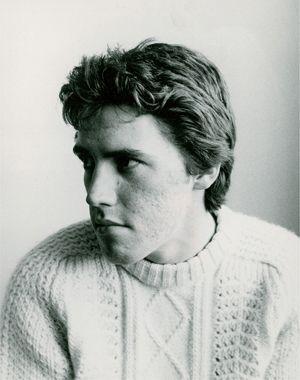

My more tempestuous relationship with acne was also in its first flush; just a few perfectly anticipated and acceptable teenage spots at first, then a slow and gradual remapping of my face until it could be said that the condition had moved in and declared squatter’s rights. The problem with acne is that friends and family, keen not to upset the sufferer, will often declare that ‘it’s not that bad, really’ when in fact it’s appalling.

It was some years before I finally went to see a dermatologist, who reacted with horror and informed me that my face was home to chronic acne. He put me on a heavy course of vitamin A, which dried out my skin and more or less put an end to the condition, although by now much of the damage had been done and the scars that I still bear today were well and truly in place. Hurrah!

As well as the acting that I was doing in rehearsals for the annual show, I was made aware of the National Youth Theatre of Wales and their month-long course in the summer, which culminated in a series of performances at Cardiff’s Sherman Theatre. Some of my fellow cast members had been on the course in previous years and spoke of it in glowing terms. There were a limited number of places available, and students would have to audition and prove themselves worthy of inclusion. So it was that a few of us hopefuls were driven up to a school in Pontypridd on a wet spring day in 1982 and sat nervously in a corridor waiting to go into the room set aside for auditions. Applicants had to perform two pieces of text: a passage from Shakespeare’s

Measure for Measure

and, if memory serves me well, a bit of Archie Rice from

The Entertainer

. The third piece could be anything at all and I had chosen, rather than a piece from a play, to perform a poem. It came from

Twelve Modern Anglo-Welsh Poets

, an anthology belonging to my mother. The poem was ‘For Instance’ by R. S. Thomas, a particularly bleak and uncompromising poet, best known perhaps for his ‘Welsh Landscape’ in which he describes my perfectly innocent, minding-their-own-business fellow countrymen as:

… an impotent people,

Sick with inbreeding,

Worrying the carcase of an old song.

‘For Instance’ is a lament from a man who has been left a widower. I pulled a few plastic chairs into a row and lay across them as though I was lying on a bed. Then, staring up at the ceiling, my sixteen-year-old self began:

She gave me good food;

I accepted;

Sewed my clothes, buttons;

I was smart.

She warmed my bed;

Out of it my son stepped.

She was adjudged

Beautiful. I had grown

Used to it. She is dead

Now. Is it true

I loved her? That is how

I saw things. But not she.

I think I might have managed to force out a tear on the last line. It was all a bit heavy for a young teenager; with hindsight, perhaps a little prophetic of

Marion and Geoff

, the series of monologues I would go on to find success with many years later (a connection I make only now). As is always the case with auditions, the poor actor leaves the ordeal none the wiser and then tries to forget about it. But I didn’t forget about it; I thought of little else until a few weeks later I discovered, much to my delight, that I had been accepted.

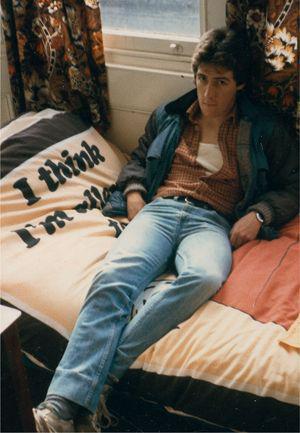

And so, that August on a warm summer’s day, Mum and Dad drove me up to Cardiff and dropped me and a select collection of my belongings off at Senghennydd House, a student hall of residence, just on the edge of the city centre and down the road from the Sherman Theatre. This whole experience was a dress rehearsal for heading off to college, four weeks spent away from home, fending for yourself and meeting new people. There was a lively mix of young personalities and types, all jostling and bumping along, trying to find their place and standing within the larger group. The only thing that linked us was a love of theatre, of acting, of performance – and the fact that, within our respective schools, we were the ones who were good at drama, the standouts, the little stars.

Darkness on the Edge of Duvet.

Here it was different; our position at the top of the league table was no longer assured. It soon became obvious to me that I was slipping down towards the relegation zone and had no need to worry myself with the responsibility of anything approaching a lead role. There were older actors there who seemed light years ahead of me in terms of confidence and accomplishment and, perhaps more notably, worldliness. They possessed a swagger which suggested that they had been around a few more blocks than I had, and might even have lingered a while on the corner of some of them.

On the first day of the course we all sat in the front few rows of the auditorium at the Sherman Theatre, knowing that in a few weeks we would be up on the stage playing to a full house. The Sherman was a modern theatre, built in the seventies, and a world apart from the pre-war design of the Grand Pavilion in Porthcawl, where we put on our yearly musical. As I sat mulling over this step up into the big time, all the students were asked to take to the stage, one at a time, and sing a song for the rest of the group. I recall Patrick Brennan, a veteran it seemed of the NYTW, ambling forward confidently to the stage and beginning a relaxed, I’m-in-my-natural-environment rendition of Fats Waller’s ‘Ain’t Misbehavin’’, all twinkly-eyed charm. Fats Waller? Why wasn’t he doing a pop song of the day? He must be quite sophisticated. He appeared to be decades older than me; he even had a beard. It wouldn’t have surprised me to learn that

The South Bank Show

was planning a retrospective of his life and work. Song complete, he sauntered back to his seat to general applause and awe.

When my turn came, I chose to stand in front of my recently appointed peers and sing Michael Jackson’s moving ballad ‘The Lady in My Life’ from his album

Thriller

. What a sensitive soul I must have seemed. And probably was.

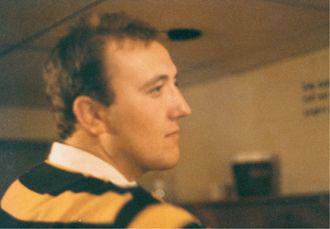

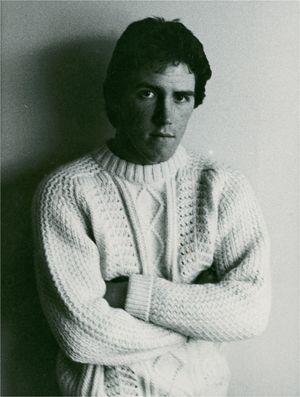

A friend had a camera. I had delusions of James Dean.

So many of them seemed older and smarter than me, and none more so than the mighty Peter Wingfield. Peter went on to become well known for his many roles, including the

Highlander

television series in America. I met him in between being crowned Welsh National Trampoline Champion and going on to study medicine at Oxford (him, not me); you could say he was a high achiever. His popularity and ease with girls was matched by his spectacular – and I use that word advisedly – ability to put his athletic gifts to everyday use. There was a tall black metal gate that led from the halls of residence out onto Salisbury Road; it must have been over six feet high. Peter would sprint up and vault over this obstacle in effortlessly superhuman fashion, during which feat he would reach a midpoint that would find him upside down, perfectly straight, with his hands gripping the top of the gate and his feet pointing skywards. He would then spring off and sail through the air to the ground, where he would land like Superman, checking the surroundings for wrongdoers.

I would watch, wide-eyed in admiration at this and other stunts, such as the time he suggested some of us visit Cardiff’s now vanished Empire Pool with its Olympic-height diving boards. A few of us ordinary boys splashed around and maybe jumped feet first off the lowest board, desperately trying not to belly flop and do ourselves an injury. In the midst of our adolescent malarkey one of the group pointed to the sky, ‘Look!’ We craned our necks upward whilst treading water. Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No, it’s Peter. He’s leaping off the highest board, spinning, twisting and turning as he plummets downwards and makes a perfect entry into the pool. My hero. I would look at someone like Peter and his levels of skill, which can only have come about through hours and hours of practice, and it would be hard not to wonder:

What have I been doing with my time?

Athletics were not the only arena in which Peter excelled. He had the room next to mine at Senghennydd House and my nights were greatly enlivened by the sound of his many and varied conquests as noises seeped through the thin wall that divided our cell-like rooms. I would lie in my bed with my Sony Walkman on, probably listening to Bruce or, if I was feeling adventurous, Hall and Oates, perhaps even Dire Straits, and then slide off my headphones, enjoy a minute or so of the Welsh Warren Beatty next door, before returning to my more innocent pursuits.

As well as befriending the superhuman Peter, I also found boys closer in experience and outlook to myself. Ian Hughes came from Merthyr Tydfil, the once great industrial town in the Rhondda Valley, and had brought his guitar with him. We spent hours singing Paul Simon and Springsteen songs together in his room. Ian would thrash wildly at his guitar and belt out early Chris de Burgh tunes; his virtuosity with his instrument again caused me to wonder what I’d been doing all these years. He went on to great success in the theatre, joining the Royal Shakespeare Company and playing the Fool to Robert Stephens’s King Lear.

The great friendship formed at the National Youth Theatre of Wales that still remains intact was with Steve Roberts, now known as Steve Speirs. Steve also came from Merthyr and though we had never met prior to this course, I’d already heard his name spoken of in hushed tones. He was a legendary figure at my school for his many exploits, witnessed by boys who had met him on previous drama courses and who had come back to regale me with their hard-to-believe tales.