Small Man in a Book (12 page)

Read Small Man in a Book Online

Authors: Rob Brydon

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

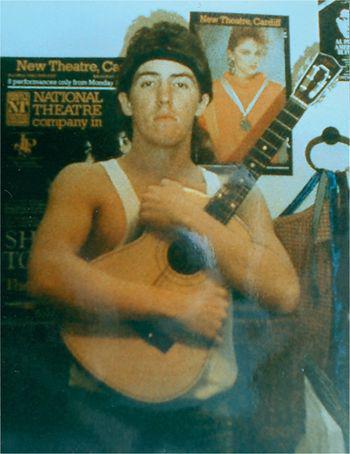

Steve Speirs, at the National Youth Theatre of Wales, aka the evil dermatologist.

Darren Gadd, Nathan to my Sky in

Guys and Dolls

, was himself no slouch when it came to benign antisocial behaviour; witness his setting off the fire hose one lunchtime in the youth wing, resulting in an impressive archipelago of puddles as far as the eye could see. The deputy head, when confronted with the small-scale flood for himself, remarked, ‘Right! Who has been spitting?’

Darren felt Steve was a man to admire and was sure we’d get on, as indeed we did. He was big, six foot one, prematurely balding (although he would now protest it was a receding hairline), a little overweight and very, very funny. Steve could find humour in anything; he had a deadpan, Tommy Cooper quality that made just looking at him funny. Unfortunately, all jokes require a victim and I unwittingly became the victim of one of Steve’s after moaning about my poor skin and bad acne which, it has to be said, was continuing its advance on my face with a determination that should have won it a Queen’s Award for Industry. Steve listened sympathetically to my woes before kindly sharing with me the secret of a special ‘Valleys’ cure that was guaranteed to work and leave me with a clear complexion. It involved sugar and water, as simple as that. It sounded like it made sense. No one spoke of ‘organic’ anything in those days – although, if they had, this scam would surely have qualified. It involved mixing some sugar with some warm water and then rubbing it, with some gusto, all over the affected areas of the face.

The morning after Steve had been compassionate enough to enlighten me, I made my way into the communal washroom and checked that the coast was clear before beginning the treatment as prescribed by Dr Roberts. It hurt. It stung.

That probably means it’s doing me good

, I thought, as I persevered with what was surely an early form of the now popular ‘self-harming’. After I felt I’d given my cheeks a thorough going-over, I patted them dry and made my way off to rehearsals. My ravaged, bloodied face and I arrived to howls of laughter from Steve and enquiries from everyone else as to whether I’d got the details of the other driver.

I swore revenge. I’m still swearing.

The whole course was geared towards the final few days of public performance. Each actor would appear in two plays, one on the main stage and one in the smaller studio space. The first year we did

Under Milk Wood

and a new play about its author, Dylan Thomas,

This Side of the Truth

, the title being borrowed from one of his poems. I can’t remember what I played in

Under Milk Wood

; it certainly wasn’t a big part or, as I think I’ve proved quite unequivocally, especially memorable. Perhaps I was one of the drowned sailors that haunt the dreams of Captain Cat. It’s just come to me, I was Nogood Boyo – not many lines and, in my portrayal of him, entirely innocent and naive with regards to what he was doing that was no good.

The play was directed by Hugh Thomas, an actor/director known to us primarily for his recent appearance in

Not the Nine O’Clock News

in which he played a mad politician in a

Question Time

sketch, memorably shouting ‘We’re all going to die!’ The fact that Hugh had worked on such a zeitgeist show added hugely to his kudos, yet his popularity had a downside with his frequent departures from rehearsals, as he once again dashed off to the stage door to take a phone call from his agent.

The other play was what would now be termed a ‘biopic’. I brought a smattering of infinitesimal roles vividly to life, although I faltered at what I now recognize was my first stunt. While some action was going on downstage, I stood upstage dressed in a nightgown and holding a lit candle. At a given moment in the proceedings I had to snuff out the flame with my thumb and forefinger, very dramatic. As a child I had an acute aversion to flames, matches, candles and to fire in general. This tiny bit of stage business used to cause me heaps of anxiety as I stood there doing bugger all at the back of the stage while the other actors got to emote their hearts out, considerably closer to the audience. Any member of that audience not transfixed by the principal players may have felt their gaze wander to the little chap at the back with the candle.

Goodness me, I think his hand is trembling. Must be cold in his nightgown.

The play had a song, written for the occasion by Dorian Thomas, which we all sang in harmony. I think it was called ‘I Remember Dylan’. It has since become the soundtrack to which many of these happy memories are set.

I remember him, I knew him well.

Met him once, he was drunk, yes

He was a boor. He was a gentleman,

He was just a child, yes

I remember him, I knew him well.

Doesn’t anyone else remember Dylan?

Dylan,

I remember Dylan.

Singing was part of the course and we would attempt it every morning with the singing coach, David Blackwell. This would take place on the main stage, which at that time appeared to me to be a vast open space, larger than any stage I’d known. I’ve since gone on to play on stages that are huge by comparison, and now look on the Sherman as a little friendly space, perfect for trying stuff out on. It’s like Bruce Springsteen says in his song ‘Straight Time’:

… you get used to anything,

Sooner or later it just becomes your life.

Any performer or artist who experiences any kind of significant success also experiences major changes to their life, if only in the size of venue in which they perform. After a while, the shock and wonder at the bigger spaces subsides and you just get on with it. Sometimes it’s good to stop and look back down the road you’ve just trundled along; it can surprise you. David would tell us to imagine the sound of our voices coming over our heads like a hood: ‘Pull the hood over your head!’ I think he subscribed to the idea of singing slightly above the note, a good discipline for someone like me who still has a tendency to sing flat. I’m not saying I do that too often – at least, I hope not – but given the choice between flat and sharp I’ll tend to take the flat option.

Before or after the singing session we’d have a period of movement/dance under the instruction of a very lithe Scot called Ian Stuart Ferguson. He would slink around the stage to the sound of George Benson’s version of ‘On Broadway’ and we would do our warm-up. It was good; for a brief moment it was as though we were part of

A Chorus Line

.

I almost felt like a dancer. For that feat alone he deserves a medal.

With the course taking place in August, the evenings were warm and long and would often be spent outdoors on the grass in front of the halls of residence. Guitars were played, someone plucking the introduction to ‘Romeo and Juliet’ by Dire Straits. Food was eaten, drink was drunk, and above us in the night sky Peter Wingfield would soar past, cape flapping in the breeze, en route to Planet Sex. Not really. Although the reality isn’t far off. He would sit on the ledge of his third-floor window, legs dangling over the edge while playing the flute, before enticing a girl back to his room and encouraging her to attempt something similar.

Sylvester Springsteen.

Steve and I would often walk into the town centre and visit one of the cinemas on Queen Street – the ABC or the Odeon. The two of us went one night to see

Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan

and both cried when Spock ‘died’. Another time a small group of us went to see

Rocky III

and I was delighted when one of the girls said she felt I looked a little like Sylvester Stallone (very much my hero at the time).

I think the perceptive girl in question was called Sarah, and I remember having quite a crush on her. In accordance with my crushes at school, this involved me getting on very well with her, teasing her a little, making her laugh and then waiting. And waiting. And waiting while another boy, slightly older and in this instance called Phil, stepped in and claimed the prize with his barbaric, Neanderthal directness. It was the sort of situation where I thought I was making progress, Phil merely popping up occasionally in my peripheral vision, until suddenly it dawned on me:

Damn, he’s with her, and it looks like he’s been there for some time

.

Much as I wanted to hate Phil, I just couldn’t. He’d only recently loaned me

Pièce de Résistance

, a legendary bootleg cassette featuring Bruce’s concert at New Jersey’s Capitol Theatre on the 19th of September 1978, part of his renowned ‘Darkness on the Edge of Town’ tour. Many regard this as Bruce’s finest ever live performance and while I’d heard rumours of the existence of this tape I’d never seen one, let alone heard one. Well, here it was. It was mine, for a while; I was allowed to borrow it! My eyes lit up as I scampered back to my little room clutching my treasure. Clever, clever Phil; he’d cunningly used the two little C-90 cassettes like a burglar throwing a poisoned lump of steak to a particularly dim-witted guard dog.

Peter Wingfield … ‘would soar past, cape flapping in the breeze, en route to Planet Sex’.

Woof, woof.

I returned to the National Youth Theatre of Wales the following year, this time to renew old friendships and play slightly, ever so slightly, bigger parts. We did Brecht’s

The Caucasian Chalk Circle

. I had very little to do in this; it was produced in such a way that a lot of the actors were sitting on stage a lot of the time, so I spent much of it watching the older actors while simultaneously losing all feeling in my lower body. I have no memory of any line spoken; I was basically an audience member with a very good view.

The Caucasian Chalk Circle

, National Youth Theatre of Wales, 1983. ‘A lot of the actors were sitting on stage a lot of the time, so I spent much of it watching the older actors while simultaneously losing all feeling in my lower body. I was basically an audience member with a very good view.’

The other production was

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

. This was more like it; I played Starveling, one of the mechanicals who put on the play

Pyramus and Thisbe

. Steve Roberts played Bottom and was hilarious; my part was smaller, but was enlivened and enlarged slightly by my taking a dog on to the stage each night. It was decided that my character would have a dog on a piece of string and this at least meant I could engineer a few laughs from disparaging looks towards the bemused creature. It only became a problem during the special matinee performance for school parties, when most of the kids in the audience began calling the dog, whistling and clicking away at him to try to encourage him to break free from my clutches. He, in return, began to bark back at them. This was very funny for about a minute, and then it wasn’t.